A recent study has revealed an extraordinary discovery about mosasaurs, the giant marine reptiles that once ruled the seas. Fossil evidence, including a mosasaur tooth found alongside T. rex remains in North Dakota, suggests that these creatures adapted to life in freshwater environments, defying previous assumptions about their strictly marine lifestyle. This finding opens new windows into understanding how species can evolve in response to dramatic environmental changes, particularly as the Earth’s ecosystems began to shift.

Mosasaur’s Freshwater Discovery: A Shift in Understanding Prehistoric Life

The ancient mosasaur, a marine predator that lived more than 66 million years ago, was long thought to inhabit only the vast oceans. But new isotope analysis of a mosasaur tooth discovered in a freshwater deposit in North Dakota suggests that, during its final years before extinction, the species may have adapted to life in rivers and freshwater environments. This groundbreaking study, conducted by an international team of scientists and reported on EurekAlert!, challenges existing theories about the habitat of these ancient reptiles.

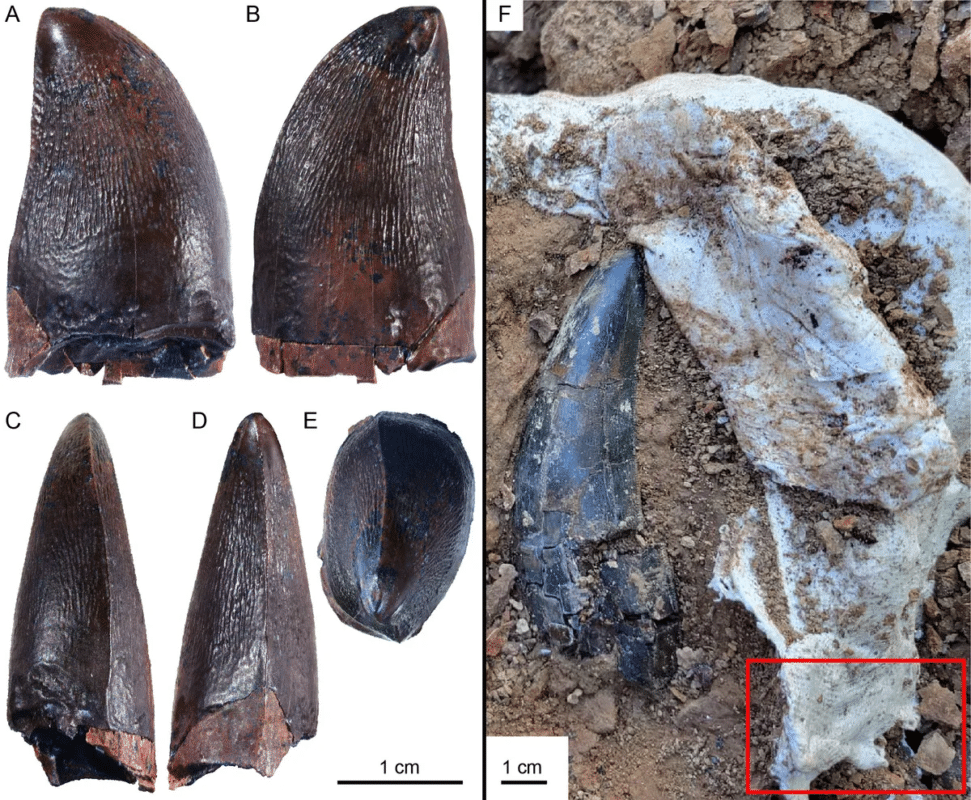

The tooth, discovered alongside a Tyrannosaurus rex tooth and a crocodilian jawbone, was originally puzzling to researchers. How did a marine reptile’s tooth end up in a freshwater deposit? The answer, it turns out, lies in the changing conditions of Earth’s ecosystems at the time. As the Western Interior Seaway began transforming from saltwater to brackish and eventually freshwater, mosasaurs appear to have followed the transition, adapting to the freshwater environments that developed.

The Science Behind the Discovery: Isotope Analysis and What It Reveals

Isotopic analysis played a crucial role in unraveling the mystery of mosasaur adaptation. Researchers analyzed the ratio of isotopes in the mosasaur’s tooth enamel, comparing it to the isotope signatures of other prehistoric fossils found in the same deposit. What they discovered was compelling: the mosasaur’s tooth contained higher levels of the lighter oxygen isotope (¹⁶O) than is typical for marine mosasaurs, indicating that it likely lived in freshwater.

Melanie During, a lead researcher on the study, explains,

“Carbon isotopes in teeth generally reflect what the animal ate. Many mosasaurs have low ¹³C values because they dive deep. The mosasaur tooth found with the T. rex tooth, on the other hand, has a higher ¹³C value than all known mosasaurs, dinosaurs, and crocodiles, suggesting that it did not dive deep and may sometimes have fed on drowned dinosaurs.” This finding provides a rare glimpse into how these apex predators might have hunted in their altered environments.

Image Credit: Melanie During

Linking Fossils and Environments: How the Mosasaur Adapted to Changing Habitats

The discovery of similar isotope signatures in additional mosasaur teeth from nearby sites further confirms the hypothesis that these reptiles adapted to freshwater habitats in their final million years. During notes, “The isotope signatures indicated that this mosasaur had inhabited this freshwater riverine environment. When we looked at two additional mosasaur teeth found at nearby, slightly older, sites in North Dakota, we saw similar freshwater signatures. These analyses show that mosasaurs lived in riverine environments in the final million years before going extinct.”

The changing conditions of the Western Interior Seaway, which shifted from salty to brackish and eventually freshwater, likely played a significant role in this adaptation. As the sea became less salty, a “halocline” likely formed, with freshwater sitting above denser, saltier water. Mosasaurs, which needed to surface for air, would have inhabited the upper, freshwater layer, where the conditions were more suitable for their survival.

Per Ahlberg, coauthor of the study, adds, “For comparison with the mosasaur teeth, we also measured fossils from other marine animals and found a clear difference. All gill-breathing animals had isotope signatures linking them to brackish or salty water, while all lung-breathing animals lacked such signatures. This shows that mosasaurs, which needed to come to the surface to breathe, inhabited the upper freshwater layer and not the lower layer where the water was more saline.”

The Giant Predator’s Size and Role in Riverine Ecosystems

The size of the mosasaur in question was another surprising aspect of this discovery. With an estimated length of up to 11 meters, this creature would have been comparable in size to the largest killer whales, making it an apex predator in both marine and freshwater environments. Such size would have made it an extraordinary predator to encounter in river systems where it could have hunted alongside or against other prehistoric giants, including T. rex and crocodiles.

Ahlberg notes, “The size means that the animal would rival the largest killer whales, making it an extraordinary predator to encounter in riverine environments not previously associated with such giant marine reptiles.” The presence of these apex predators in freshwater systems suggests that even large marine creatures could find their place in changing environments, adapting in ways we’re only now beginning to understand.

The Complexity of Evolution: From Marine to Freshwater

The transition from marine to freshwater environments represents a complex evolutionary shift, but it may not have been as difficult for the mosasaurs as once believed. Unlike the more complicated adaptation needed to move from freshwater to marine environments, the reverse process is generally simpler, according to Melanie During. This insight broadens our understanding of how species might cope with environmental changes over time, adapting their biology to suit new challenges.

“Unlike the complex adaptation required to move from freshwater to marine habitats, the reverse adaptation is generally simpler,” she says. Modern examples, such as river dolphins and estuarine crocodiles, demonstrate how certain species can thrive in both freshwater and marine environments, showing that these adaptations are possible even for large predators.