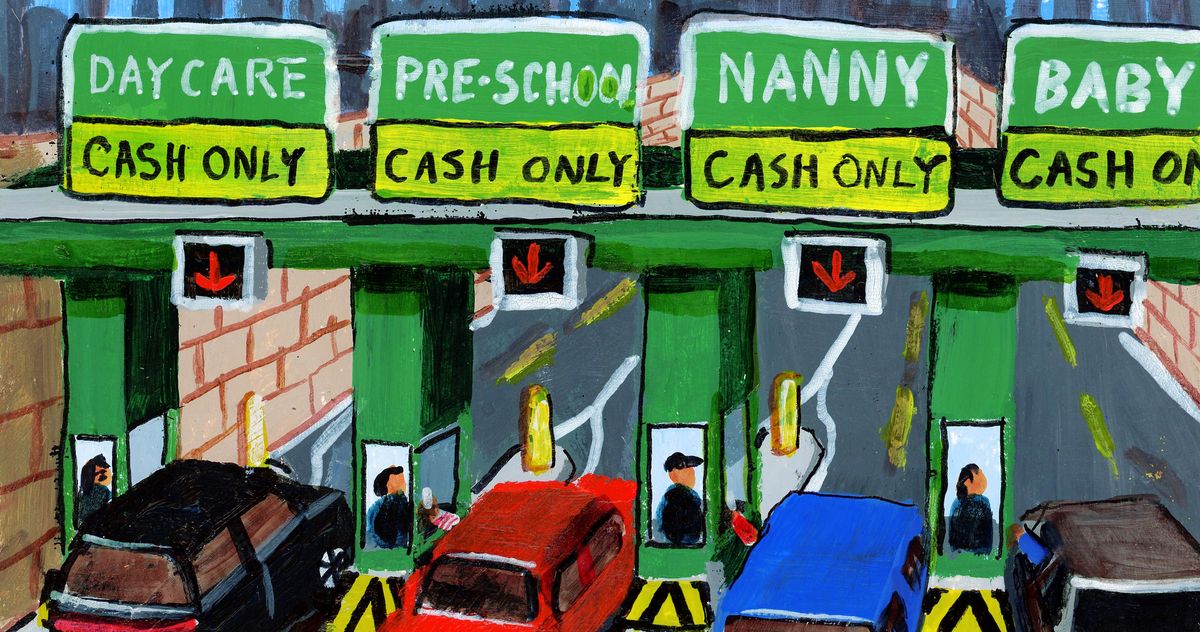

Illustration: Brandon Celi

Recently, a Manhattan father-to-be dipped into a local Facebook parenting group for an opinion on the “mind-boggling” $2,400 a month he had been quoted from a nearby day-care center for his baby due in March. But instead of shock or empathy, he was largely met with jaded mocking. “Sounds like a steal,” responded one parent. Another advised him to stay away from such “low-cost ones,” like she did. Still another let him know, “On the UES it’s $3,800, so …”

In New York City, “having it all” (a full-time job, one toddler, a full-time day-care spot) now requires, at minimum, an annual family income of $334,000 — assuming you don’t want to spend more than 7 percent of your income on child care, which is what the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says is the federal standard for affordability. (This benchmark was derived by the Obama administration not through any careful equation, but rather by averaging out what parents paid for child care between 1997 and 2011, Elliot Haspel, a national child-care policy expert and author of Raising a Nation, has written.) It’s a flawed calculation, but it also reveals a hideous truth: Child care is unaffordable for 80 percent of NYC parents — a stat that many New Yorkers might find laughably absurd if it weren’t so debilitating. For a number of moms and dads I’ve talked to, paying a nanny’s salary, a monthly day-care bill, day-camp tuition, or fees for after-school programs easily consumes 25 to 50 percent of their family’s after-tax pay. I even talked to parents who tapped into savings for the privilege of keeping their careers afloat through some of the most hands-on parenting years.

“We have reached a crisis point,” says Grace Rauh, executive director of Citizens Union, home to the 5BORO Institute. She points to the findings of a comptroller report released early this year: The average cost of infant and toddler care at small, in-home providers, which make up the most popular of the city’s regulated child-care options at that age, is $18,200 a year. This price rose nearly 79 percent between 2019 and 2024 — an increase Rauh calls “staggering.” During that same period, center-based facilities, which now charge $26,000 per year (on average), saw a 43 percent tuition increase. The cost of child care has dramatically outpaced inflation, which in the New York City area rose 20 percent between 2019 and 2024, while average hourly earnings increased by just 13 percent.

Paying for day care is so unbelievably unaffordable and out of reach for families that it threatens the very bedrock of the city’s economy by pushing many parents to quit their jobs, says Rauh. More than two out of every five New Yorkers say they or another adult in their household turned down paid work due to child care, according to a 2023 Cornell University poll. Of those parents, more than half said they didn’t take a job because child care was too expensive. It’s an issue Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani campaigned, and won, on, promising free child care for all New Yorkers between 6 weeks and 5 years old, coinciding with increased wages for child-care workers, a quarter of whom live in poverty.

But his plan still wouldn’t solve a series of secondary child-care problems for parents of school-age children: The school day ends hours before the average workday (which often necessitates hiring hourly babysitters to ferry kids to after-school programs and sports practices, which themselves can cost a few thousand per semester); the school-year calendar contains more than a week’s worth of holidays on which school is closed but virtually all workplaces stay open; and summer day-camp tuitions can be exorbitant. Oasis Day Camp, which operates out of Central Park and caters to working parents with free early drop-off and late pickup, charges more than $1,000 per week for an eight-week camp session. And at the popular Park Slope Day Camp, which has programs in Prospect Park, the camp day ends at 4 p.m. (kids can stay in camp activities until 6 p.m. for an extra fee), and an eight-week “traditional camp” session is $6,100. Parents who opt for “bus camps” that take their children out of the city for the day often pay much more — as much as $10,000 per camper for a full summer including transportation.

Randi Rivera is a freelance stage manager who lives in Brooklyn with her partner, Ben, a customer-service worker for educational technology. The couple talks about whether she should quit her job to stay home with their almost-2-year-old at least once a month. Rivera grew up in New York, and her grandmother babysat her every day — a free child-care arrangement that she’s unable to replicate. So for now, the couple has opted against formal child care for their toddler due to the $21,500 annual cost they were quoted and instead juggle the duties themselves. “It feels like we’re in a house of cards,” Rivera says. “We’re existing on a thin line and can’t make any sudden movements in any direction.”

To understand how New Yorkers got here, you have to go back to 1971, when President Richard Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Act after it passed with bipartisan support in Congress, says Haspel. The bill gained momentum just as for-profit child-care chains were starting to pop up around the country, signaling a true need for expanded child care, and would have started to fund a locally administered system of high-quality child care for all families. But Nixon buckled to organized opposition from the right (citing government overreach), and by the end of the 1970s, both parties had largely stopped pursuing the idea of comprehensive child-care reform. “We’ve never really recovered from that,” says Haspel. Parents today still face the same fundamental problem they did 50 years ago, but with the added complication of an intractable day-care shortage.

The pandemic caused hundreds of day-care facilities in New York City to shutter, and some that initially survived have since closed with the pullback of emergency federal funding. In 2022, there was only enough licensed child care in the city to serve 46 percent of children under 5. “There’s just a kind of true market failure here, where supply doesn’t keep up with demand because it is really, really hard for folks to actually open and operate that supply,” says Emmy Liss, the independent consultant who co-authored the 2024 child-care report for 5BORO.

Day-care centers that remain currently compete with fast-casual restaurants and grocery stores for hourly workers. According to the January comptroller report, in 2023, New York City’s 32,917 employed child-care workers had a median income of just $25,000. That’s 45 percent of the median income of all other city workers, and the lowest median income of any “care work” occupation, including home health aides, personal-care aides, nursing assistants, and preschool and kindergarten teachers. Haspel says that when pandemic child-care aid expired in 2023, there was talk among advocates about falling off the child-care cliff. “Now,” he says, “instead of a cliff, what we’re getting is this slow, painful roll down into the ravine.”

A difficult truth about New York’s broken child-care system: Despite the exorbitant costs to parents, the vast majority of providers are not getting rich. In fact, many barely break even.

For day-care centers, one of the biggest obstacles to profitability is real estate, says Liss. Since September 2008, the city’s health code has required center-based programs serving infants and toddlers to be located on the ground floor, typically the most expensive part of a commercial building. And to operate, they must adhere to complex space-use requirements, for which architects and contractors must be hired. Then, once a facility is up and running, the operating costs — liability insurance, frequent staff training, and especially payroll for the staff — are extremely high. Even centers that receive public subsidies for qualified children, such as federal vouchers or Head Start funding, often find the assistance is not enough to cover their bills.

In-home child-care providers, nearly 80 percent of whom are renters, also face severe costs. In surveys by the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation, a community-development organization supporting and training at-home child-care providers in the city, 57 percent of providers reported not being able to make ends meet despite most (nearly 70 percent) working 50 hours per week. For these businesses, the most serious threat to viability is staffing, says Gregory Brender, chief policy officer at the Day Care Council of New York, a child-care-program membership organization. Employees are underpaid, and group teachers at child-care centers (who are required to have a New York State Teaching Certificate or be enrolled in a program leading to certification) make “significantly less” than if they were doing the same job in a public school. Adds Robert Cordero, CEO of the nonprofit Grand Street Settlement, which operates 14 child-care sites for low-income families around the city, “Teacher assistants are some of the lowest-paid members of society in New York and beyond.”

Ana Escoto of the Bronx has been an in-home child-care provider for 21 years. “Parents are right; it is expensive for them,” she told me. But what many people don’t know, she adds, “is that providers cannot keep much of that money. We need it for food, rent, insurance that is very high, cleaning supplies, materials, and especially staff.”

Escoto struggles with staff turnover because she pays her employees between $16.50 and $20 per hour, which is the maximum she can afford. The cyclical nature of her business — children inevitably grow up and move on and, lately, exit earlier than she expects due to free school-based 3K and pre-K programs — sometimes leaves her with as few as five or six enrolled children when she has the capacity to care for 16. It is worth noting that she is also operating in a landscape of entrenched injustice: “The early-childhood system is mostly women and mostly women of color,” says Brender, “and we often see these kinds of pay disparities in professions that are female-dominated.” In a good year, Escoto told me, she clears between $35,000 and $45,000.

Perhaps more than they do anywhere else, families without a day-care seat in New York turn to nannies and babysitters — a largely unregulated and uncounted part of the child-care market that has its own set of financial pitfalls. According to census data, about 14,000 nannies work in New York City. The real number is undoubtedly much higher because 90 percent of nannies nationwide are estimated to work off the books, without collecting social-security or disability benefits. Although nannies are often associated with high-earning families, many parents struggle to pay their nannies’ salaries. “I have young families who are thriving with a high income but have minimal net worth,” says Guy Maddalone, author of How to Hire a Nanny and CEO of GTM Payroll & HR, which offers household payroll services, human resources, and insurance. “The income is coming in, but it’s all going right out the door. Families are very conscious of that, and also keenly aware of what their neighbors are paying.”

Alice (not her real name), a mom of one who works in marketing and whose husband works in postproduction for film and TV, recently let her nanny go and hired two part-time babysitters instead for different days of the week. “When we had our full-time nanny, we ate into our savings each month,” she says. For part of that time period, she was laid off and looking for a job but kept her nanny on with full pay to maintain consistency for her child. “It was definitely a struggle,” she says.

The “going rate” for a nanny or babysitter, as parents I interviewed referred to it, is currently between $25 and $35 an hour for one child, but it can go up, in rare cases, to $50 an hour, depending on the certifications the caregiver holds and the number of children in their care. Park Slope Parents, which has been conducting surveys about nanny pay in Brooklyn for years, found in 2025 that, among 742 families surveyed, the pay for one child ranged from $23 to $30 an hour. For two kids, it increased: $24.60 to $34.84. If you apply the “7 percent of household income” formula here, using the average hourly pay rate for one child from this sample, that means a family must make at least $700,000 annually for a full-time nanny to be considered “affordable.” Parents employing nannies told me they feel paralyzed by the financial outlay and requests for raises and bonuses, and there are few guardrails in place to help them come to a solution. (For many parents, a nanny is the first employee they have ever managed.) The nannies, too, feel financial stress; even those who are relatively well paid don’t make enough to afford child care of their own. And because they work in a silo — without co-workers or human resources — navigating salary-related problems can feel impossible.

At her most recent job, one longtime New York City nanny I spoke to was paid $25 an hour to care for one child, a job that included school pickup, dinner prep, room tidying, and laundry. But soon, her taskload was expanded to include vacuuming the apartment, planning and preparing dinner for the whole family, watering the plants, and running errands — all with no raise. She was given two weeks off for Christmas with no pay and was never compensated when her employers came home late, which was often. Eventually, she was “dismissed overnight” and, she found out, replaced with someone who would take a lower salary.

Some parents told me that they believe their nanny has an inaccurate understanding of how much money they have and what they can afford. “I just don’t like the expectation of, like, ‘Well, you’re a physician, and you should be paying more,’” a Manhattan mom of two told me. “That’s definitely an unfair expectation and a case of, ‘I’ll change my rate based on what I think you can afford.’” If she and her husband could actually swing $35 instead of $25 an hour, she says, they would.

Stacy Kono, executive director of the educational nonprofit Hand in Hand: The Domestic Employers Network, points out that there may be a “going rate” for nanny pay, but just because a price is common doesn’t make it fair. “We believe employers should pay a living wage and go beyond what’s in the minimum-wage laws,” she says, noting that the MIT living-wage calculator tool estimates $33 an hour as a living wage in New York City for a single adult and $55 an hour for a single adult who is supporting one child — significantly more than child-care workers typically receive in either center-based or at-home settings.

Some families can afford to pay salaries at this level, contends Alene Mathurin, founder of the grassroots organization My Nanny Circle, but don’t simply because the standard rate among their peers is lower. She views the stagnancy of nanny wages as a serious flaw in the child-care system. “For example, a nanny starts to work with a family for $25 an hour and has spent four years working with a child until they go to school, getting a small increase each year. Then the family no longer needs her full-time. She moves on to another family in the same Zip Code. But it’s almost like she goes back to square one, starting again at that $25 an hour.” Too often, she says, the nanny’s accrued experience doesn’t seem to matter.

There’s also a powerful and unhelpful relationship dynamic at play when it comes to nanny pay rates, says Maddalone. “The family always feels like the nanny is just an extension of their family,” he says. They unconsciously conflate the nanny with warm family figures in the child’s life, like a grandmother or close friend, letting overtime and occasional favors (a load of their laundry, a bathroom that needs a deep clean) slip by unpaid. The nannies, he says, “think of it more as a job.”

In Brooklyn, as Randi Rivera’s toddler continues to grow and working while watching the child becomes more difficult, discussions with her partner about whether to become a stay-at-home mother are giving way to another, arguably more drastic question: Should they move to her partner’s hometown of Madison, Wisconsin, where they have family to watch their kids?

Many New York parents seem to have a similar idea. Between 2020 and 2023, the population of children age 3 and under in New York dropped by nearly 20 percent — a trend that predates the pandemic as well as the rise of hybrid and remote work. From 2019 to 2022, Manhattan lost 9.5 percent of its under-5 population. The majority of families who left were middle-income New Yorkers.

“His parents are really extremely helpful, and his siblings are there,” Rivera says, explaining her thinking. “And we have looked at houses and we’re familiar with the schools to kind of get a feel for what our life might be like.” She admits it could be a good life, but she hates the lack of diversity in Wisconsin in comparison to the city. Plus, leaving the city where she has lived her entire life would be heart-wrenching. “It’s not how I was hoping to raise my kids,” she says.

Related