In 2004, astronomers spotted a planet-like object orbiting Fomalhaut, one of the brightest stars in the night sky. With further observations, however, it started to look more like a dust cloud—a decidedly less exciting outcome. Astronomers have now made an unexpected second observation around the same star: an apparent collision of two gigantic planetesimals—a decidedly incredible and important finding.

Paul Kalas, who discovered the ex-exoplanet, has been tracking Fomalhaut since the object’s discovery in 2004. Accordingly, Kalas, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, knew better than anyone that the newly discovered dot, seen sparkling at the fringe of the star’s dust ring, definitely wasn’t there before. Further analysis strongly suggested that Kalas and his colleagues had captured two asteroid-like planetesimals smashing into each other. This in turn produced a bright dust cloud—something astronomers had never seen unfold in real time. The new findings were published today in Science.

“I would have had to have been the luckiest astronomer in the world to see it,” Kalas told Gizmodo in a video call, “because these collisions only happen once every 100,000 years.”

Fomalhaut and the luckiest astronomer

Kalas and Fomalhaut go way back. The astronomer first studied the star as a student in 1993 and identified the exoplanet candidate Fomalhaut b from continued observations. In addition, he discovered a large belt of dusty debris roughly 133 astronomical units (AU) from the host star (1 AU is the average distance from the Earth to the Sun, so this band is quite far from its host star).

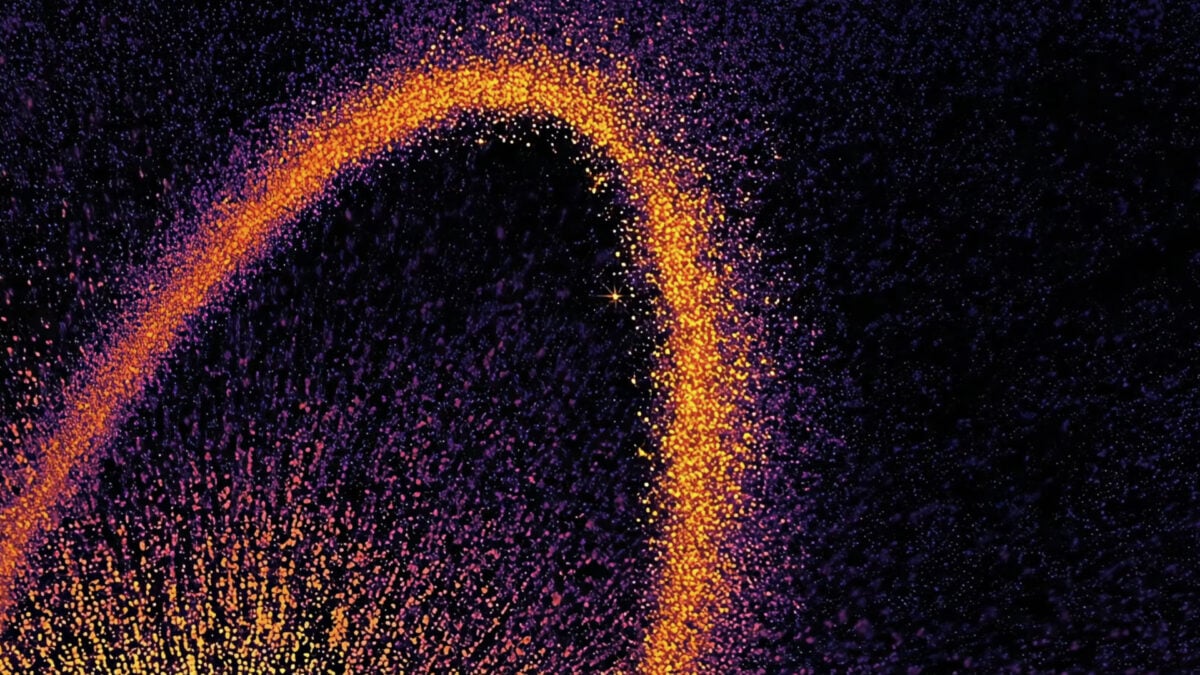

Fomalhaut, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA/ESA/Digitized Sky Survey 2/Davide De Martin (ESA/Hubble)

Fomalhaut, captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA/ESA/Digitized Sky Survey 2/Davide De Martin (ESA/Hubble)

In 2002, study co-author Mark Wyatt devised mathematical models that suggested large objects in the dust belt should occasionally collide and light up, but very rarely. And when they do, “they’ll create little points of light that we will be able to observe,” Wyatt, an astrophysicist at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom, told Gizmodo during a phone call.

Then, two years later, Kalas spotted Fomalhaut b. At the time, the object moved very much like an exoplanet, leading Kalas and other astronomers to conclude that it was a planet. But there was some controversy over if it really was—or, for that matter, if it even existed.

“Some people called it a zombie planet,” recalled Kalas. Then around 2013, astronomers noticed that Fomalhaut b’s path had curved away from a star, more like tiny particles comprising a dust cloud, not a solid planet.

“[A] planet can’t appear out of nowhere. But a dust cloud can.”

Finally, the “planet” disappeared from sight, and the community concluded that the object must have been an expanding dust cloud. Accordingly, NASA’s official exoplanet archive removed Fomalhaut b from the list in 2020.

Fomalhaut b, 2.0?

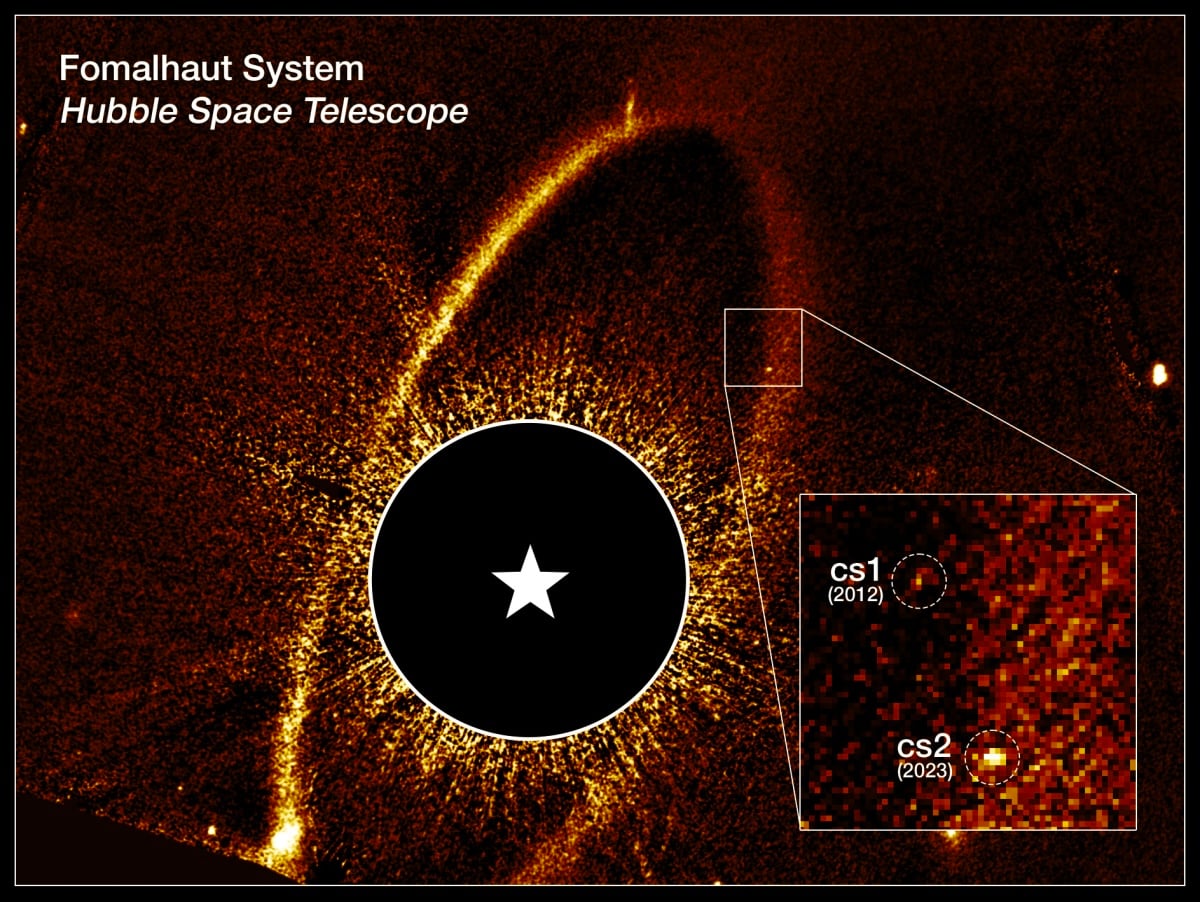

But the story was far from over. Three years after the disappearance of Fomalhaut b—renamed “circumstellar source 1,” or cs1—Kalas found “another Fomalhaut b,” he said. “And the reason we say it solved the mystery [of Fomalhaut b] is because a planet can’t appear out of nowhere. But a dust cloud can.”

Here’s what that means. The intense swirling of matter around Fomalhaut clumps up into asteroid-like objects big enough to collide and create a giant dust cloud. This cloud reflects light—just like a planet—so it “masquerades as a planet for a while,” Kalas explained. Eventually, the cloud becomes less dense, and radiation from the host star pushes it out of orbit, making the signal vanish.

A composite Hubble image showing the debris ring and dust clouds surrounding Fomalhaut. Credit: NASA/ESA/Paul Kalas (UC Berkeley)/Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

A composite Hubble image showing the debris ring and dust clouds surrounding Fomalhaut. Credit: NASA/ESA/Paul Kalas (UC Berkeley)/Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

In a similar vein, the 2023 source, cs2, recently emerged from another rare yet sizable asteroid collision. The impact poofed up into a radiant dust cloud observable by our telescopes, just as Wyatt predicted in 2002. But as he himself admitted, the new observation did come as a surprise.

“Well, I knew that the model was right, but the model being right doesn’t mean that you can actually detect that,” Wyatt admitted.

The cosmic laboratory

The familiarity of asteroid collisions betrays the fact that, scientifically speaking, humanity hasn’t been able to directly see it happen, Kalas said. “You see animations of collisions—like, the asteroid hitting Earth and wiping out the dinosaurs,” he said. “Asteroid collisions are inferred or fantasized about. These are the first observations in astronomy [that], in real time, we are seeing the collision happen.”

An artist’s interpretation of the collision of two planetesimals in the debris disk of Fomalhaut. Credit: Thomas Müller (MPIA)

An artist’s interpretation of the collision of two planetesimals in the debris disk of Fomalhaut. Credit: Thomas Müller (MPIA)

That has big implications for astronomy, the researchers said. For instance, because it’s difficult to track and observe asteroid collisions, NASA had to send two expensive spacecraft and smash them against each other to figure out what happens when things collide in space, Wyatt explained.

Fomalhaut is a natural laboratory that allows researchers to study celestial collisions without multibillion-dollar missions, he said. What’s more, the collisions provide astronomers with clues into the composition of these objects, the larger of which are also called planetesimals, the progenitors of planets.

Already, Kalas, Wyatt, and their colleagues have been granted more time with Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope, which they plan to dedicate toward studying circumstellar source 2.

“Is it getting brighter or fainter? Does it have colors that resemble asteroids or comets? Does it become larger? Can we detect it changing shape?” Kalas mused. “We’ve learned our lesson to obtain as many more observations as possible!”