The winners of the annual W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography — one of the largest grants in support of the photographic arts that opened for entries in July — have been announced and the winner is Palestinian-American Maen Hammond, for his project Amira’s Castle, an ongoing exploration of his grandparents’ lives and his own documentation of the Palestinian present.

The W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography is now in its 46th year and has awarded more than $1.4 million over that time to photographers whose past work and proposed projects follow in the tradition of W. Eugene Smith’s career as a photographic essayist.

“We continue to be impressed and amazed at the quality of entries we receive each year, and the incredibly diverse stories photographers are sharing with the world,” Scott Thode, president of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund, says. “It is the continued generosity of our longtime donors including the Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation, Joy of Giving Something, Earth Vision Institute, the John and Anne Duffy Foundation, and PhotoWings, which allow us to provide funding for these incredible stories.”

This year, the Grant saw 657 entries representing 74 countries. The annual awards are divided into six grants, each worth a considerable sum. The main grant is $30,000, there are two finalists of $10,000 each, two student grants of $5,000 each, and the Howard Chapnick Grant of $7,500.

Below, each caption is provided by the photographer.

Winner – $30,000 Award

Maen Hammad received the $30,000 W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography for his project, Amira’s Castle. At its center are three threads – his grandfather Mohammad’s revolutionary archive, his grandmother Amira’s daily practice of tending to the land they reclaimed, and his own documentation of the struggle unfolding today. Together they form a dialogue across time, drawing the archive and the land into conversation—and pressing Maen to confront what his responsibility is in carrying those legacies forward today.

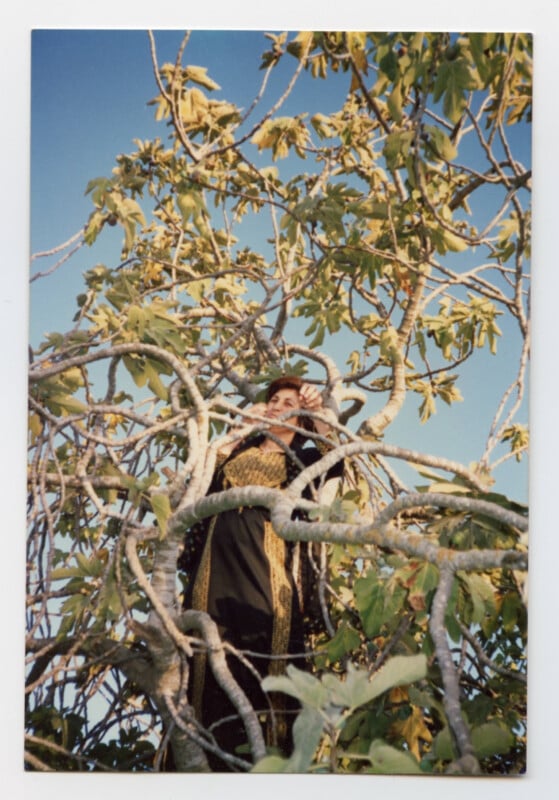

A photograph taken by my mother of my grandmother climbing a fig tree during one of her visits in Helhul, Palestine between 1988 and 1992.

A photograph taken by my mother of my grandmother climbing a fig tree during one of her visits in Helhul, Palestine between 1988 and 1992.  My grandfather speaking on the microphone in Tetuan, Morocco during a lecture on pan-Arabism in 1959 where he was organizing Moroccans recently liberated from Spanish colonization.

My grandfather speaking on the microphone in Tetuan, Morocco during a lecture on pan-Arabism in 1959 where he was organizing Moroccans recently liberated from Spanish colonization.  The demolished home of the Nakhle family in the Jalazon refugee camp near the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, 2023.

The demolished home of the Nakhle family in the Jalazon refugee camp near the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, 2023.

“This project is profoundly personal, yet collective,” Maen says of his project. “It is a story about my grandparents, the small piece of land they returned to, and my people’s ongoing struggle for liberation. In the face of decades of erasure that have failed to unmake us, carrying this archive into the present through images is a responsibility I hold deeply.”

Apricot season on my grandmother’s land, 2025.

Apricot season on my grandmother’s land, 2025.  The blood-stained cement of Awdeh Hathaleen’s body, a Palestinian activist and filmmaker killed by an Israeli settler, 2025.

The blood-stained cement of Awdeh Hathaleen’s body, a Palestinian activist and filmmaker killed by an Israeli settler, 2025.  Pomegranate season in my grandmother’s land in Helhul, Palestine, 2025.

Pomegranate season in my grandmother’s land in Helhul, Palestine, 2025.

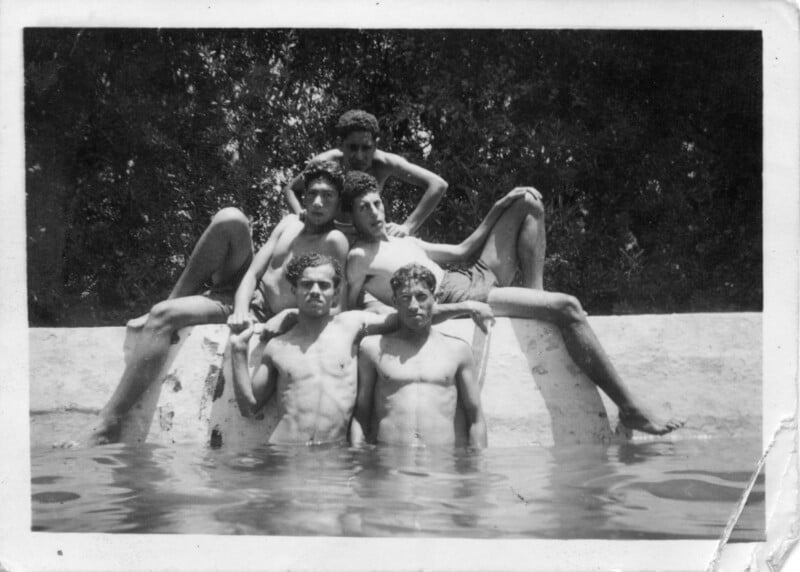

My grandfather (top) and his friends at a spring in Tulkarem, Palestine while a university student sometime between 1946-1948.

My grandfather (top) and his friends at a spring in Tulkarem, Palestine while a university student sometime between 1946-1948.  The funeral of Yasser al-Kasba, aged 17, who was shot and killed by an Israeli sniper, 2023. Finalists – $10,000 Award

The funeral of Yasser al-Kasba, aged 17, who was shot and killed by an Israeli sniper, 2023. Finalists – $10,000 Award

Rena Effendi from Turkey was awarded the Finalist award of $10,000 for her work, The Shrinking Sea, which traces changes along the Caspian Sea, including pollution and drying reed beds, as well as other losses scientists believe may be irreversible.

Assos, Turkey, 2022. Inside an abandoned house on the Aegean coast, discarded clothes mark the traces of people who waited for clandestine crossings to Lesbos, Greece. Through the window they could see Europe, close enough to feel like freedom yet still out of reach.

Assos, Turkey, 2022. Inside an abandoned house on the Aegean coast, discarded clothes mark the traces of people who waited for clandestine crossings to Lesbos, Greece. Through the window they could see Europe, close enough to feel like freedom yet still out of reach.  Dakar, Senegal, 2025. At the Mbeubeuss landfill, a young man carries a huge bundle of plastic down the hill while others sort through the trash behind him. For many, this exhausting work is an in-between stage, a way to earn enough money to perhaps take the next step and move on.

Dakar, Senegal, 2025. At the Mbeubeuss landfill, a young man carries a huge bundle of plastic down the hill while others sort through the trash behind him. For many, this exhausting work is an in-between stage, a way to earn enough money to perhaps take the next step and move on.  Dakar, Senegal, 2025. One of the people working on the Mbeubeuss landfill is Ami Ndiaye (26), who regularly travels from Kaolack with her two-year-old son Babacar to earn money for their survival and a hoped-for future elsewhere. His small TikTok backpack in the background hints at a distant digital world far from their own.

Dakar, Senegal, 2025. One of the people working on the Mbeubeuss landfill is Ami Ndiaye (26), who regularly travels from Kaolack with her two-year-old son Babacar to earn money for their survival and a hoped-for future elsewhere. His small TikTok backpack in the background hints at a distant digital world far from their own.  Dakar, Senegal, 2025. At the Mbeubeuss landfill outside Dakar, people from across West Africa pick through the waste alongside cattle and birds, searching for metal, electronics and plastic they can resell. Earning only a few dollars a day without protection, many treat this toxic hillside as both a last refuge and a way to save in the hope of one day being able to leave.

Dakar, Senegal, 2025. At the Mbeubeuss landfill outside Dakar, people from across West Africa pick through the waste alongside cattle and birds, searching for metal, electronics and plastic they can resell. Earning only a few dollars a day without protection, many treat this toxic hillside as both a last refuge and a way to save in the hope of one day being able to leave.

Nefta, Tunisia, 2024. Near Nefta, a man who has just crossed from Algeria walks alone through the desert, carrying everything he owns under a heavy coat and gloves for the freezing nights. For many people heading toward Europe, everything begins with days in this empty landscape long before they ever see the sea.

Nefta, Tunisia, 2024. Near Nefta, a man who has just crossed from Algeria walks alone through the desert, carrying everything he owns under a heavy coat and gloves for the freezing nights. For many people heading toward Europe, everything begins with days in this empty landscape long before they ever see the sea.  Sfax, Tunisia, 2024. In an abandoned warehouse at the edge of the city, Sudanese teenagers Ismad (17) and Hassan (22) share a cramped room with other young men who fled the war in Khartoum. They sleep, cook and wash in the same cold space while trying to collect enough money for a dangerous boat crossing to Europe.

Sfax, Tunisia, 2024. In an abandoned warehouse at the edge of the city, Sudanese teenagers Ismad (17) and Hassan (22) share a cramped room with other young men who fled the war in Khartoum. They sleep, cook and wash in the same cold space while trying to collect enough money for a dangerous boat crossing to Europe.  Sfax, Tunisia, 2024. On the outskirts of Sfax, the main departure point toward Europe, this section of the cemetery is reserved for people who drowned at sea and could not be identified. While Tunisian citizens have headstones with their names, these graves are marked only by bricks scratched with numbers.

Sfax, Tunisia, 2024. On the outskirts of Sfax, the main departure point toward Europe, this section of the cemetery is reserved for people who drowned at sea and could not be identified. While Tunisian citizens have headstones with their names, these graves are marked only by bricks scratched with numbers.  Lampedusa, Italy, 2023. On a rocky beach, a tourist sunbathes and reads beside a rusted metal boat used by people who arrived days earlier, their clothes and makeshift flotation rings still scattered on the shore.

Lampedusa, Italy, 2023. On a rocky beach, a tourist sunbathes and reads beside a rusted metal boat used by people who arrived days earlier, their clothes and makeshift flotation rings still scattered on the shore.

Stefanos Paikos (Berlin / Athens) also received a $10,000 Finalist grant for his story, Reaching for Dusk: Mbeubeuss, which chronicles Mbeubeuss, a massive open-air landfill on the outskirts of Dakar, Senegal. It has become an unlikely waypoint on the journey toward Europe. Some are fleeing political instability, others the impossibility of making a living.

Shikhov beach, one of the last stretches of public shoreline near Baku, remains accessible while most of the Caspian coast has been privatized. Soviet-era oil rigs stand stagnant in the background, relics of decades of extraction. As water levels continue to fall and industrial development presses closer, places like this—where ordinary residents can still touch the sea—are becoming increasingly rare. Baku, July 2016.

Shikhov beach, one of the last stretches of public shoreline near Baku, remains accessible while most of the Caspian coast has been privatized. Soviet-era oil rigs stand stagnant in the background, relics of decades of extraction. As water levels continue to fall and industrial development presses closer, places like this—where ordinary residents can still touch the sea—are becoming increasingly rare. Baku, July 2016.  In Naftalan, crude petroleum long used in spa baths is drawn not from the Caspian but from inland oil fields. The spa’s “healing” black-oil treatments represent an intimate connection to Azerbaijan’s oil heritage, even as the Caspian Sea itself suffers decline. In Naftalan, about 330 km west of Baku, this facility treats conditions like arthritis and skin ailments with oil believed to have antiseptic and anti-inflammatory effects. 29 July 2016.

In Naftalan, crude petroleum long used in spa baths is drawn not from the Caspian but from inland oil fields. The spa’s “healing” black-oil treatments represent an intimate connection to Azerbaijan’s oil heritage, even as the Caspian Sea itself suffers decline. In Naftalan, about 330 km west of Baku, this facility treats conditions like arthritis and skin ailments with oil believed to have antiseptic and anti-inflammatory effects. 29 July 2016.

Balakhani, scarred by decades of oil extraction and littered with waste, reflects the lasting toll of industry on the Caspian’s fragile edge. Baku, 2010.

Balakhani, scarred by decades of oil extraction and littered with waste, reflects the lasting toll of industry on the Caspian’s fragile edge. Baku, 2010.  A boy from a community of the internally displaced flexing muscles by a Soviet-era oil rig in Balakhani village. Baku, Azerbaijan. 2010.

A boy from a community of the internally displaced flexing muscles by a Soviet-era oil rig in Balakhani village. Baku, Azerbaijan. 2010.  A discarded gas mask floats in an oil puddle in Balakhani on the outskirts of Baku. Once at the center of the world’s first petroleum boom, the fields are now scarred by waste and neglect, their toxic pools a reminder of how deeply the Caspian’s shores bear the cost of extraction. Baku, 2010.

A discarded gas mask floats in an oil puddle in Balakhani on the outskirts of Baku. Once at the center of the world’s first petroleum boom, the fields are now scarred by waste and neglect, their toxic pools a reminder of how deeply the Caspian’s shores bear the cost of extraction. Baku, 2010.  People rest along the newly reconstructed promenade by the Caspian Bay, known as the Baku Boulevard. In the background, international hotel chains rise above the waterfront, symbols of rapid development built on a fragile sea already shrinking under the pressure of climate change and decades of exploitation. Baku, July 2016.

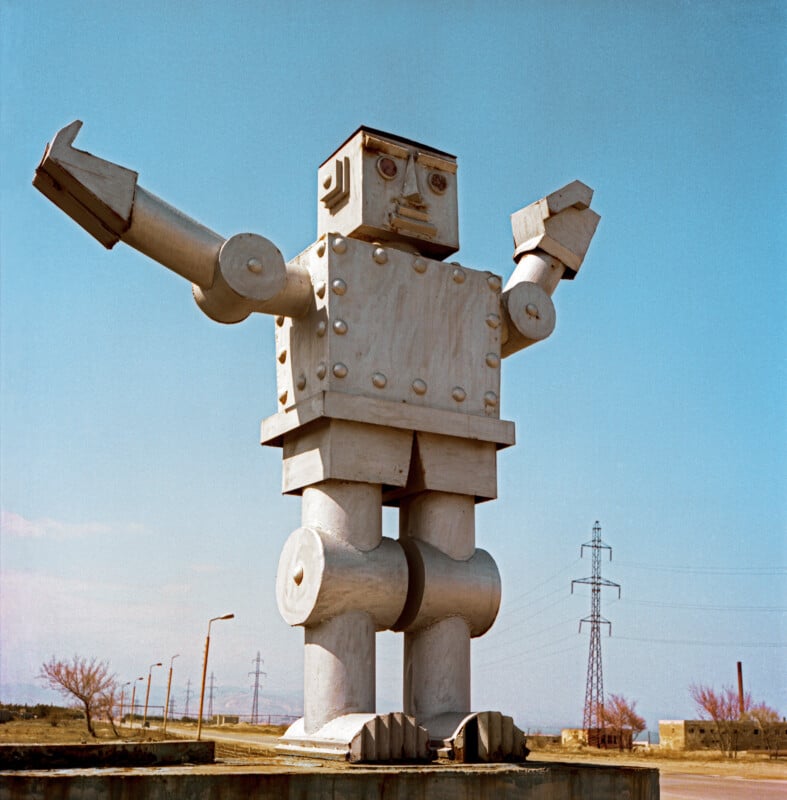

People rest along the newly reconstructed promenade by the Caspian Bay, known as the Baku Boulevard. In the background, international hotel chains rise above the waterfront, symbols of rapid development built on a fragile sea already shrinking under the pressure of climate change and decades of exploitation. Baku, July 2016.  A Soviet-era statue of a robot stands outside an abandoned petrochemical factory in Sumgait, a city about 30 km (19 miles) north of Baku. Once a cradle of Soviet industrial might, its chemical plants are now largely derelict, spitting pollutants into the Caspian and leaving rusting relics to decay along the shore. Sumgait, 2007.

A Soviet-era statue of a robot stands outside an abandoned petrochemical factory in Sumgait, a city about 30 km (19 miles) north of Baku. Once a cradle of Soviet industrial might, its chemical plants are now largely derelict, spitting pollutants into the Caspian and leaving rusting relics to decay along the shore. Sumgait, 2007.  A ship graveyard rusts into the waters off Nargin Island, just outside Baku Bay. Once engines of industry, these hulks now leach metal and oil into the sea, corroding as the Caspian itself recedes. They stand as reminders that the sea is both a resource and a dumping ground, carrying the weight of past exploitation into an uncertain future. Baku, 2006. Student Grant Winners – $5,000 Awards

A ship graveyard rusts into the waters off Nargin Island, just outside Baku Bay. Once engines of industry, these hulks now leach metal and oil into the sea, corroding as the Caspian itself recedes. They stand as reminders that the sea is both a resource and a dumping ground, carrying the weight of past exploitation into an uncertain future. Baku, 2006. Student Grant Winners – $5,000 Awards

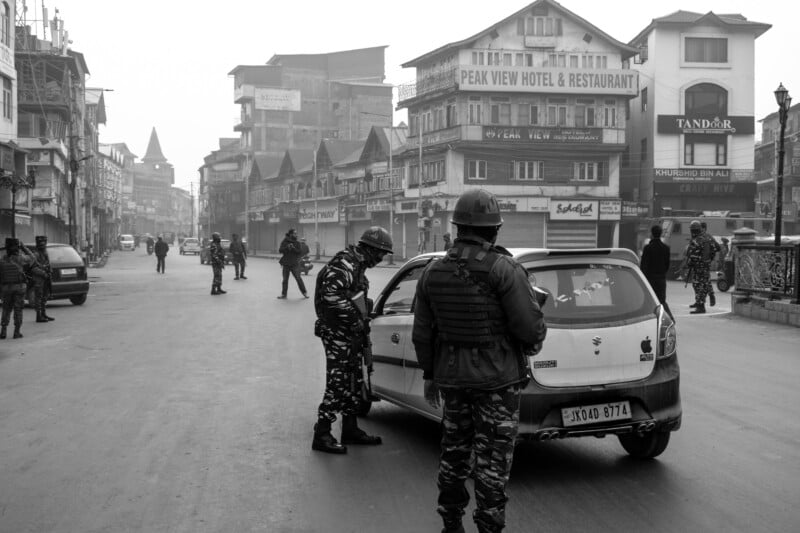

Mumin Gul (Kashmir) is one of this year’s Smith Student grant recipients and attends Pathshala South Asian Media Institute in Bangladesh. His project, Silent Whispers, is primarily based in Indian-administered Kashmir. It is a visual exploration of the nuances of the Kashmir conflict and daily realities of ordinary Kashmiris.

A boy reacts to getting scolded by other kids in Dargah, Srinagar, on 4th April 2019.

A boy reacts to getting scolded by other kids in Dargah, Srinagar, on 4th April 2019.  Frozen Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir on 14 January 2021.

Frozen Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir on 14 January 2021.  A bullet hole inside the room of an encounter site, where two militants including a top commander Nadeem Abrar was killed in an operation in Srinagar’s Maloora locality after the latter was detained at a checkpoint in the city outskirts earlier on Monday, June 28.

A bullet hole inside the room of an encounter site, where two militants including a top commander Nadeem Abrar was killed in an operation in Srinagar’s Maloora locality after the latter was detained at a checkpoint in the city outskirts earlier on Monday, June 28.  An Indian military personnel checks inside a vehicle at a security checkpoint in Lal Chowk, Srinagar, Kashmir on November 19, 2021.

An Indian military personnel checks inside a vehicle at a security checkpoint in Lal Chowk, Srinagar, Kashmir on November 19, 2021.  A boy fires a toy gun from the window of his house towards his friends as they run in Downtown, Kashmir, on Eid Ul Azha on 2nd August, 2020.

A boy fires a toy gun from the window of his house towards his friends as they run in Downtown, Kashmir, on Eid Ul Azha on 2nd August, 2020.  Martyrs Graveyard in Dal Gate, Srinagar on 15 January, 2021.

Martyrs Graveyard in Dal Gate, Srinagar on 15 January, 2021.  The women look towards the relic, believed to be the hair of the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) at Dargah. Hazratbal, Srinagar on 8th December, 2017. Over the years, these places of worship have become places of psychotherapy as the conflict has taken a toll on human emotions.

The women look towards the relic, believed to be the hair of the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) at Dargah. Hazratbal, Srinagar on 8th December, 2017. Over the years, these places of worship have become places of psychotherapy as the conflict has taken a toll on human emotions.

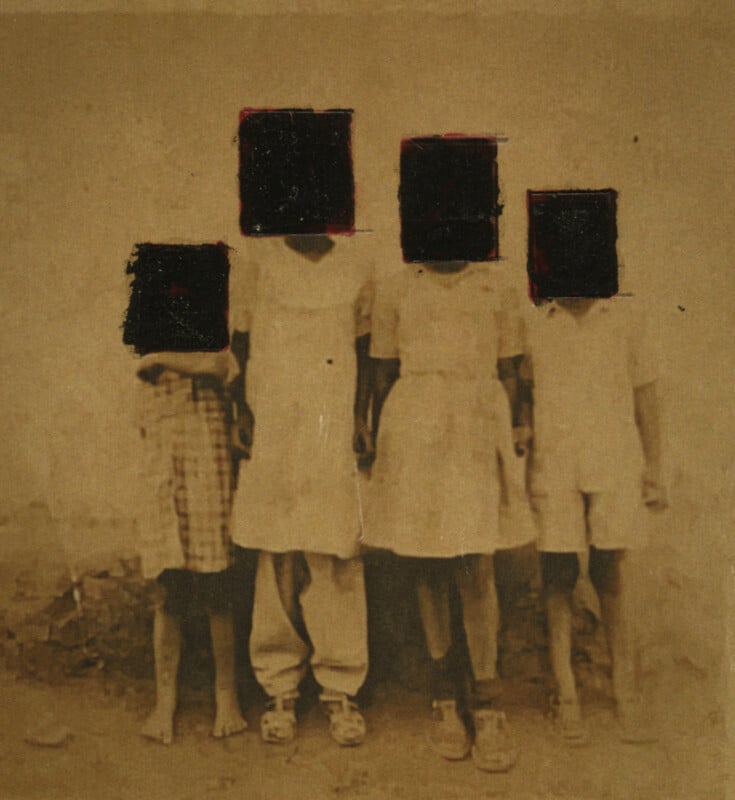

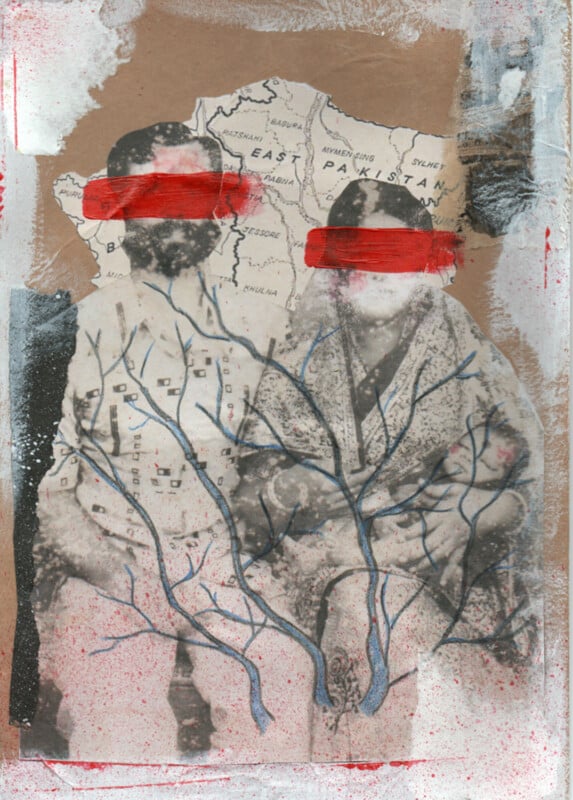

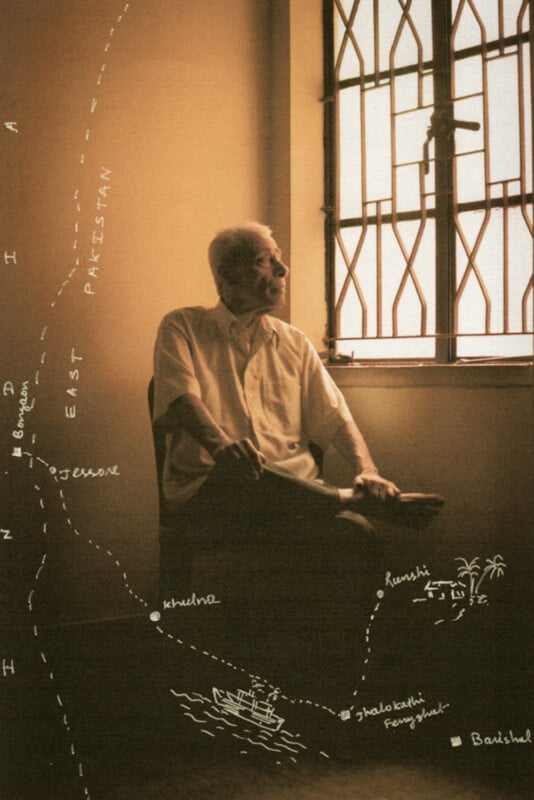

Shubhadeep Mukherjee (New Delhi) is a student at Jamia Millia Islamia University in India. His project, Smells Like Home, is inspired by his father’s journey as a 5-year- old from then-East Pakistan to India after Indian Independence in 1947. Smells Like Home is Shubhadeep’s personal narrative that explores the concept of ‘Home’ from the perspective of childhood.

An old family photograph that I found in my father’s box. He does not recognize the ones in the photo. Old age is overpowering his memory and with a heavy voice, Baba narrates how he had lost his siblings the day after they had reached the Indian mainland. This photograph now stands as a testament to the untold stories of partition, of families torn apart and lives forever altered. My father still keeps it in his old trunk that reminds him of his childhood and the playful evenings.

An old family photograph that I found in my father’s box. He does not recognize the ones in the photo. Old age is overpowering his memory and with a heavy voice, Baba narrates how he had lost his siblings the day after they had reached the Indian mainland. This photograph now stands as a testament to the untold stories of partition, of families torn apart and lives forever altered. My father still keeps it in his old trunk that reminds him of his childhood and the playful evenings.  My mother holds a hand-painted, dried palm leaf hand fan, a quintessential item in a Bengali household. My mother’s family too was forced to flee their hometown. While my mother and all her siblings were born in India, she had heard stories from her father. This traditional hand fan has a cloth wrapped around the frills. Ma says that the cloth is from one of her grandmother’s saris that her mother had sewn onto it, just to preserve the memory of the childhood home, a poignant symbol of resilience and memory. The intimate scene evokes the enduring cultural practices that survivors carried across borders after the Partition of India. The brass tumbler by her side is a family heirloom that adds to the quiet narrative of displacement, survival, and the longing for a lost home.

My mother holds a hand-painted, dried palm leaf hand fan, a quintessential item in a Bengali household. My mother’s family too was forced to flee their hometown. While my mother and all her siblings were born in India, she had heard stories from her father. This traditional hand fan has a cloth wrapped around the frills. Ma says that the cloth is from one of her grandmother’s saris that her mother had sewn onto it, just to preserve the memory of the childhood home, a poignant symbol of resilience and memory. The intimate scene evokes the enduring cultural practices that survivors carried across borders after the Partition of India. The brass tumbler by her side is a family heirloom that adds to the quiet narrative of displacement, survival, and the longing for a lost home.  An old family photograph that I found in my father’s box. He does not recognize the ones in the photo. Old age is overpowering his memory and with a heavy voice, Baba narrates how he had lost his siblings the day after they had reached the Indian mainland. Thousands of children were lost, some to hunger and sickness, and some to violence never to be found again. This photograph now stands as a testament to the untold stories of partition, of families torn apart and lives forever altered. My father suffers from acute insomnia and if he is sleeping, he often yells in his sleep. He still holds a tight grip while sleeping. My father suffers from a post-traumatic stress disorder that prevents him from sleeping for longer hours. At this age, it adds to his distress. My father still keeps it in his old trunk amidst the multiple documents he has. It reminds him of his childhood and the playful evenings.

An old family photograph that I found in my father’s box. He does not recognize the ones in the photo. Old age is overpowering his memory and with a heavy voice, Baba narrates how he had lost his siblings the day after they had reached the Indian mainland. Thousands of children were lost, some to hunger and sickness, and some to violence never to be found again. This photograph now stands as a testament to the untold stories of partition, of families torn apart and lives forever altered. My father suffers from acute insomnia and if he is sleeping, he often yells in his sleep. He still holds a tight grip while sleeping. My father suffers from a post-traumatic stress disorder that prevents him from sleeping for longer hours. At this age, it adds to his distress. My father still keeps it in his old trunk amidst the multiple documents he has. It reminds him of his childhood and the playful evenings.  Old photographs are supposedly the only heirloom my family had left me with. Our otherwise affluent life had transformed to a humble one overnight when my father’s family was forced to flee to India. That was the sole option if one wanted to live and hence, they had packed their lives in a few trunks and sailed to India. Like I found these photographs kept aside in a box, it feels like the memories of the bygone days have also been locked and put away, never to be spoken about for they carry the pain of losing one’s home. Most of these photographs are orphaned images that my father has no memories of.

Old photographs are supposedly the only heirloom my family had left me with. Our otherwise affluent life had transformed to a humble one overnight when my father’s family was forced to flee to India. That was the sole option if one wanted to live and hence, they had packed their lives in a few trunks and sailed to India. Like I found these photographs kept aside in a box, it feels like the memories of the bygone days have also been locked and put away, never to be spoken about for they carry the pain of losing one’s home. Most of these photographs are orphaned images that my father has no memories of.  This is the photograph of Mr. Dilip Mukherjee (my father). There is barely any sunlight in our old apartment and my father’s favorite spot is this window in my room and that too remains unopened for the wind. I asked him to sit there and speak to me when I made this photograph. My father was 5 years old when one afternoon, my grandfather stormed in and announced the plans to depart. At almost 80, he has faint memories of his journey. He had barely spoken about his experiences earlier and that day we spoke for almost two hours when he narrated those fond memories that he recollects with happiness. The child in my father also recollects the memories of crossing Jhalokathi in a steamer and he had asked his father, “When are we coming back, Baba?”

This is the photograph of Mr. Dilip Mukherjee (my father). There is barely any sunlight in our old apartment and my father’s favorite spot is this window in my room and that too remains unopened for the wind. I asked him to sit there and speak to me when I made this photograph. My father was 5 years old when one afternoon, my grandfather stormed in and announced the plans to depart. At almost 80, he has faint memories of his journey. He had barely spoken about his experiences earlier and that day we spoke for almost two hours when he narrated those fond memories that he recollects with happiness. The child in my father also recollects the memories of crossing Jhalokathi in a steamer and he had asked his father, “When are we coming back, Baba?”  A freshly cut fish, blood still oozing, tells a story beyond its immediate appearance. For eight-year-old Gayetri Das Sharma, freshly arrived in India after the Dhaka riots, seeing half a fish and a slice of pumpkin in her father’s hand was bewildering. Back home beside the river Padma, her father, a doctor, had received fresh fish from local boatsmen as a gesture of respect for his service to the community. The fragment of fish marked not just scarcity, but a new reality, a child’s first encounter with displacement, adaptation, and the quiet dignity of survival.

A freshly cut fish, blood still oozing, tells a story beyond its immediate appearance. For eight-year-old Gayetri Das Sharma, freshly arrived in India after the Dhaka riots, seeing half a fish and a slice of pumpkin in her father’s hand was bewildering. Back home beside the river Padma, her father, a doctor, had received fresh fish from local boatsmen as a gesture of respect for his service to the community. The fragment of fish marked not just scarcity, but a new reality, a child’s first encounter with displacement, adaptation, and the quiet dignity of survival.

Mustard oil lamps are lit on the tulsi mancha in every home, continuing a ritual that once filled open courtyards. Anadi Ranjan Ray, a Partition survivor from Feni, recalls the small tulsi plant at his family home and the daily evening offerings it received. Today, with smaller living spaces, the sacred plant is often confined to a corner, yet the ritual endures as a quiet act of devotion, memory, and continuity of home.

Mustard oil lamps are lit on the tulsi mancha in every home, continuing a ritual that once filled open courtyards. Anadi Ranjan Ray, a Partition survivor from Feni, recalls the small tulsi plant at his family home and the daily evening offerings it received. Today, with smaller living spaces, the sacred plant is often confined to a corner, yet the ritual endures as a quiet act of devotion, memory, and continuity of home.  The photograph of a dhaak (a special kind of drum used during Durga Puja). During Durgotsav (during the month of march) at the century-old Ekchala Durga mondop, the rhythmic beats of the dhaak echoed through the village. Once the annual zamindar puja, it drew people from nearby villages, Hindus and Muslims alike, who came together to witness the celebration. Today, 95-year-old Ajit Kumar Guha, who survived the Noakhali riots, recalls those days when the sound of the drums marked both faith and community. Howard Chapnick Grant – $7,500 Award

The photograph of a dhaak (a special kind of drum used during Durga Puja). During Durgotsav (during the month of march) at the century-old Ekchala Durga mondop, the rhythmic beats of the dhaak echoed through the village. Once the annual zamindar puja, it drew people from nearby villages, Hindus and Muslims alike, who came together to witness the celebration. Today, 95-year-old Ajit Kumar Guha, who survived the Noakhali riots, recalls those days when the sound of the drums marked both faith and community. Howard Chapnick Grant – $7,500 Award

Uvas y Hojas, a cultural center and the only bookstore in El Pescadero, Baja California Sur, is the recipient of this year’s ($7,500) Howard Chapnick grant. What began in 2021 as a small gathering of eight photographers in a walkway has blossomed into a vital community hub. Their monthly event, Foto Viernes, now brings together the work of a dedicated group of 22 local photographers, aged 16 to 80, to share and present free workshops for the public on everything from composition to visual storytelling.

Photographers share work at a Foto Viernes event at the original venue in 2023.

Photographers share work at a Foto Viernes event at the original venue in 2023.  Sandra Reyna hangs an exhibition of work by local photographers at Uvas y Hojas in 2025.

Sandra Reyna hangs an exhibition of work by local photographers at Uvas y Hojas in 2025.

They have cultivated a thriving arts scene from the ground up, and with this grant, they aim to channel their community’s creative energy toward a pressing local issue. Uvas y Hojas is run and operated by Sandra Reyna, Dominic Bracco II, and Paco Oropeza.

Sean Mosval performs a song during an open mic for poetry, corridos, and rap at Uvas y Hojas in October 2025.

Sean Mosval performs a song during an open mic for poetry, corridos, and rap at Uvas y Hojas in October 2025.

Local photographer Fatima Gonzalez with her image at the opening of an exhibition for students from the National Geographic Photo Camp Baja California Sur in 2025 hosted at Uvas y Hojas.

Local photographer Fatima Gonzalez with her image at the opening of an exhibition for students from the National Geographic Photo Camp Baja California Sur in 2025 hosted at Uvas y Hojas.

“This funding not only directly supports our students and provides access to essential creative resources but also allows us to invest in the infrastructure of our space,” Sandra Reyna says. “This will strengthen our ability to continue this work long-term, giving us the confidence to build upon the foundation we have laid over the last five years, and ensure that the crucial issues our community faces are addressed.”

Image credits: Photographs provided courtesy of the W. Eugene Smith Fund