A German man is on trial for allegedly drugging, raping and filming his unconscious wife for nearly 15 years in a case that has been called the “German Pelicot.”

On Friday, a verdict is expected in the case of a 61-year-old school janitor, who, prosecutors say, raped his wife from 2009 to 2024. The alleged abuse took place inside the couple’s home and was filmed and then shared online without the victim’s knowledge, according to prosecutors.

The verdict at the Regional Court of Aachen in western Germany comes exactly a year after Frenchman Dominique Pelicot – who solicited dozens of strangers from a chatroom for a near 10-year period to rape and abuse his then-wife Gisèle – was found guilty of aggravated rape. Forty-nine other men were all found guilty of rape or sexual assault.

The case, which unfolded over months in southeast France, shocked the country and brought global attention to the way that France approaches gender-based violence amid a culture of pervasive misogyny. It sparked a cultural reckoning on violence against women that the country is continuing to grapple with.

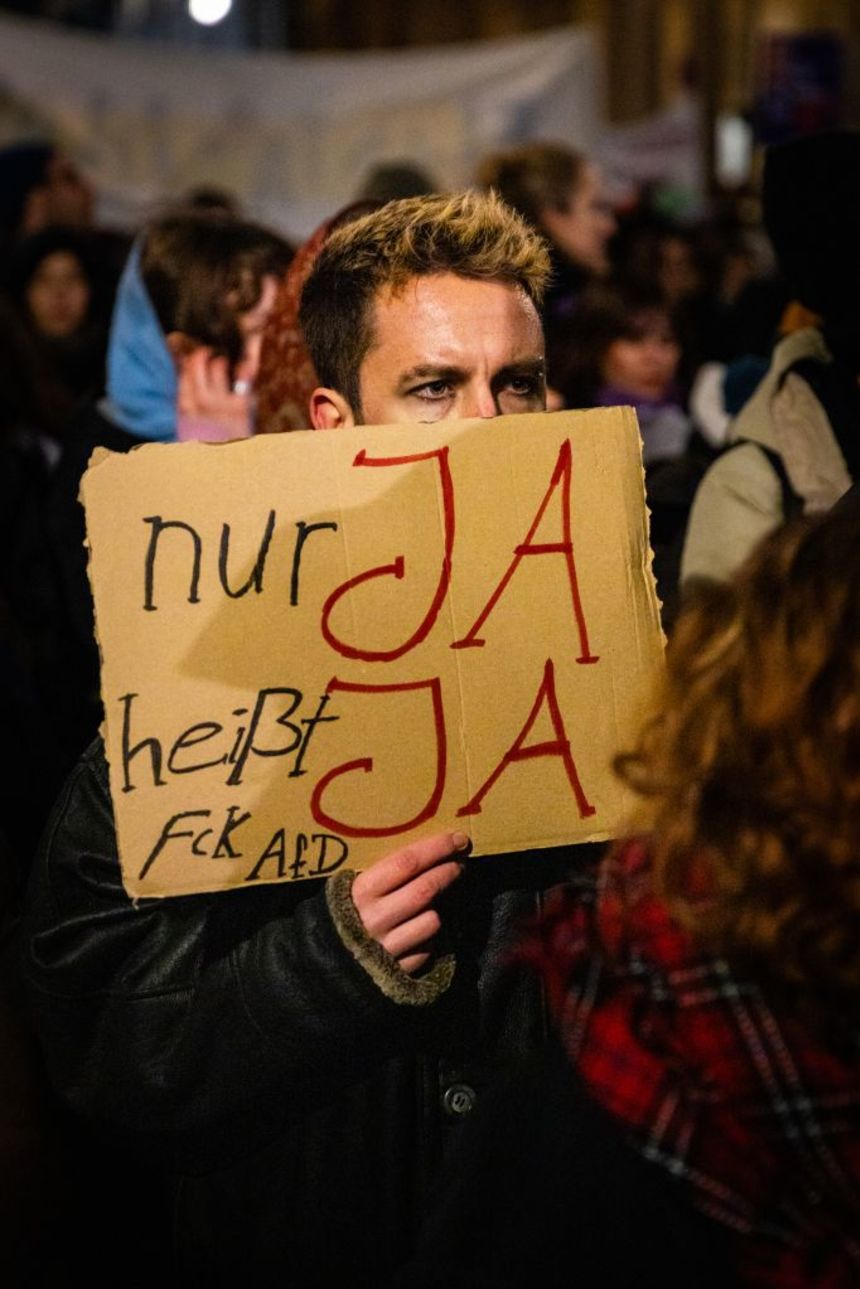

The Aachen case is the first of its kind to be heard by the German courts, according to the campaign group Nur Ja Heisst Ja, whose name – translated to “Only Yes Means Yes” – highlights its mission to change how rape is legally defined.

Last year, Hamburg-based investigative journalists unearthed evidence of a man who, for 14 years, had shared videos on an adult website allegedly showing the drugging and raping of his wife. But that man was never charged; he passed away in 2024.

The Aachen case is ” very significant,” said Jill S., an activist from Nur Ja Heisst Ja who asked CNN not to use her last name to avoid online abuse, because “It’s a case that kind of shows where there are gaps in our legal system.”

In Germany, consent has traditionally been defined through the “no means no’” principle, which campaigners say deprives victims of sexual abuse – particularly those who have been drugged, as is alleged in the Aachen case – the ability to give explicit consent for sexual acts.

Nur Ja Heisst Ja are campaigning for the German government to change the definition of rape to include a “yes means yes’’ standard, arguing that the current law still places the burden on victims to verbally resist rape and other sexual violence.

Like “any kind of topic around sexual violence, it’s not taken very serious by the government,” Jill S. said.

The Aachen case also highlights another key problem, according to the campaigners: The possession of rape content is currently legal in Germany.

Nur Ja Heisst Ja is hopeful that this might soon change, as Kathrin Wahlmann, a justice minister in the state of Lower Saxony, has launched a statewide campaign to have that possession criminalized.

Across the border in France, lawmaker Sandrine Josso also believes that laws need to be adapted to protect women from this kind of abuse.

For Josso, the issue is personal.

In November 2023, Josso alleges she was drugged by then 66-year-old French senator Joël Guerriau at a party.

She filed a criminal complaint, with a trial beginning in January.

Guerriau has denied all allegations.

“I think that today’s laws are not sufficiently grounded in reality,” Josso told CNN, saying that she believes that current laws do not factor into account how the online world fuels unique eco-systems of abuse.

“Social media has enabled it (sexual abuse) because communities form and share tips – essentially refining and professionalizing their methods. That’s what makes it so alarming,” she said.

Both Pelicot and the defendant in the Aachen case, according to prosecutors, used free messaging platforms to connect and share their abusive content.

Josso said that websites and chatrooms hosting rape content are like an “online university of violence” where men can teach each other how to drug their partners and revel in sharing footage of their alleged crimes.

For Jill S. in Germany, online platforms and governments have a lot to answer for when it comes to addressing the spread and propagation of this content.

“I think the sad thing is that all of these men felt really, really safe sharing this content, putting it online, leaving thousands of videos on their laptops at home.”

She hopes Friday’s verdict may help to finally shatter this illusion of safety and lead to the conviction of more abusers.