Earnhardt had a tough year in 1996, breaking his sternum and collarbone in a wild, tumbling crash at Talladega in July. It was the worst accident of his career so far, but at 44 years of age the fire still burned fiercely. He was on the grid for the following weekend’s race at Indianapolis but had to pull in after six laps to hand over to relief driver Mike Skinner. The Man in Black then showed true grit at Watkins Glen the weekend after that where he qualified on pole and led more than half the race before falling back to finish sixth. But Earnhardt was far from fit and the rest of the season was a struggle. “We beat ourselves up, lost a lot of confidence because we ran so bad after the Talladega wreck,” said Earnhardt at the time. “I was hurt, recuperating, and we got down on ourselves. We didn’t fall apart but we questioned ourselves in a lot of ways. Some guys left because they didn’t think we could put the team back together.”

For 1997 Childress expanded his team to run a second car for Skinner, but for the first time in 16 years Earnhardt failed to win a race, although he was able to scrape home fifth in the championship. The next year couldn’t have started better as he finally won the Daytona 500, but the rest of the season was dominated by Gordon, who won 13 races and took his second championship in a row. Earnhardt trailed home a distant eighth in the title race, more than 1000 points behind Gordon. But Earnhardt showed signs of resurgence in 1999 and 2000. He won three races in ’99 and scored two more wins in 2000 as well as finishing second to Bobby Labonte in the championship. By then he was 49 and beginning to think about retirement. His son Dale Jr had won NASCAR’s second-division Busch series in 1998 and ’99 driving for Dale Earnhardt Inc, and then made a successful move into the top-level Cup series with DEI in 2000, winning two races and taking a couple of poles. At the time Earnhardt talked about retirement with the Washington Post‘s motor sports writer Liz Clarke.

“I worry that when I do say, ‘Hey, I’m gonna retire in 2005’, or whatever it is, whether I really can retire?” he told her. “Can you comfortably retire and walk away from it? Maybe the race team ownership and being involved that way. This is what I’m thinking: Dale Jr’s coming along, and say five or six years down the road Dale Jr is starting to make it. If I’m involved with him, or if he’s involved with our programme, then it may be easier to retire.

“I surely don’t want to race too long. I think AJ Foyt raced too long. And I think Richard Petty would have really liked to retire a little earlier. But I bet Richard has the fire inside him that he would still enjoy the driving part of it. I don’t know. That’s the part I worry about: when I do think it’s time — or when time says it’s time — whether inside I can accept it and retire.

“Everybody has their time,” Earnhardt went on. “And I’m still having mine and I’m enjoying it. Maybe I’m not right at the peak of it as much as I was. But I’m still there. I’m still a factor and a contender, and by no means ready to throw in the towel and give up and hand over the flag. Some son-of-a-bitch is going to have to take it from me.”

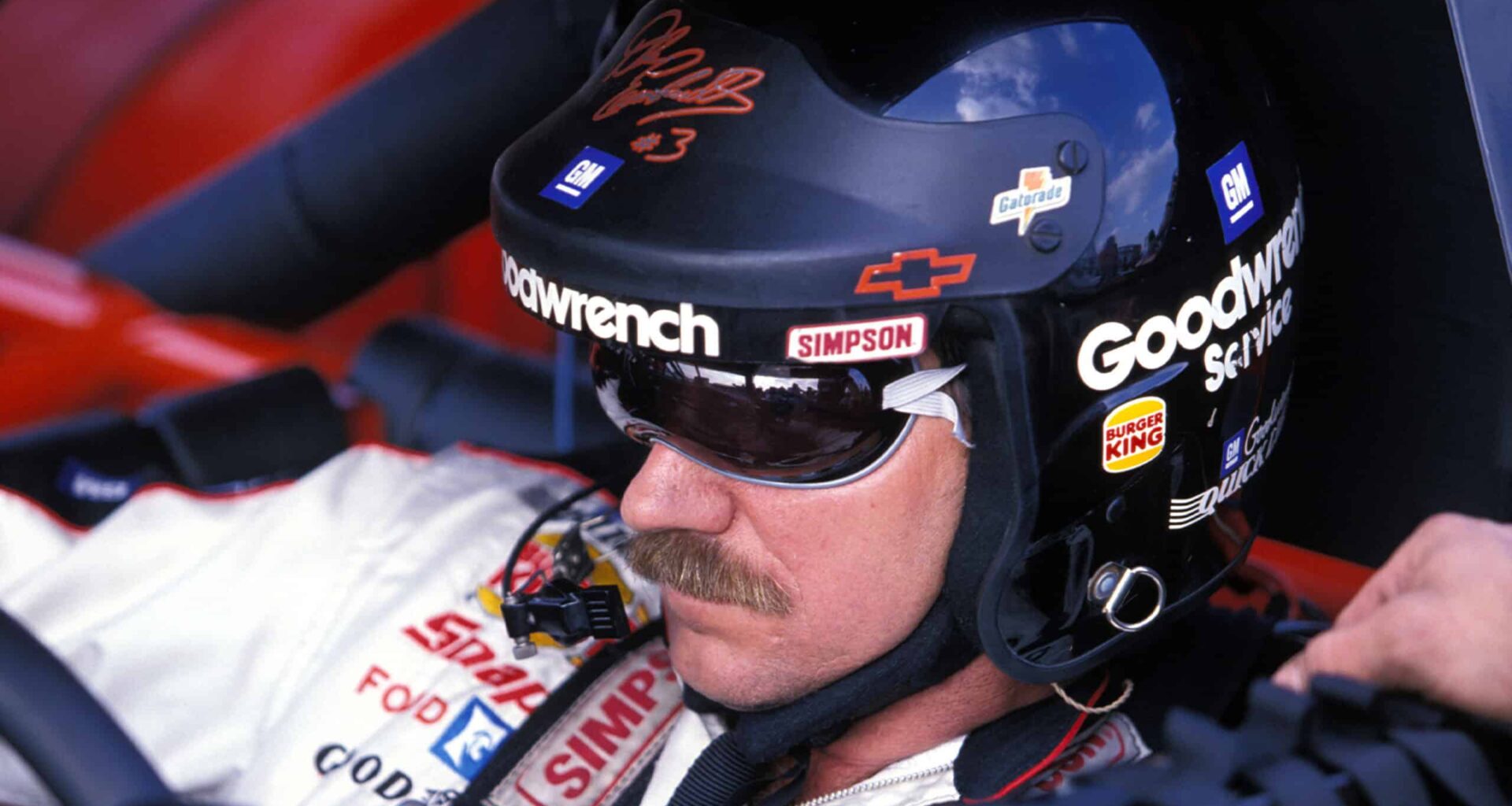

Earnhardt clutches his fourth Winston Cup Series trophy in 1990

Getty Images

Until the day he died, Earnhardt was the acknowledged master of drafting on the superspeedways. He seemed to understand how to use the air better than any other driver and his results at Daytona and Talladega proved it. At Talladega, Earnhardt won no fewer than 10 500-miles races, and despite winning the Daytona 500 just once those 33 other victories at the track over the years, including a string of 10 consecutive 125-mile qualifying races between 1990-99, tell the real story. He was also a grand master of ‘laying a fender’ on another car. Unlike most forms of motor racing, stock car racing is a contact sport. Using your car’s fenders to best effect is one of the arts of the game, and nobody could do it better than The Intimidator. Over the years Earnhardt crashed many people, always with a deft touch. He played the odds and won many times. He raised the ire of plenty of drivers and even more fans, emerging as the man people loved to hate.

In a US Scene column last spring I described a day at Daytona 20 years ago when Earnhardt crashed into Al Unser Jr‘s tail on the last lap of an IROC race, knocking Unser ‘out of the ballpark’. Earnhardt went on to win the race, while Unser walked away shaken but unhurt. It was a salubrious lesson for Unser and I’ll always remember Earnhardt’s great rival and sometimes pal Rusty Wallace scowling about the incident. “Now you know why we all hate him,” Wallace barked.

As stated, Earnhardt was despised as much as he was loved. Today, the myth is that everyone admired and respected him, but that’s hardly the truth of the matter. Sure, he loved to hunt and fish and joke with his fellow drivers, but he was as tough and hard-edged as they come. In many ways it is ironic that Earnhardt’s death had such an effect on NASCAR’s lax ways with safety, because he loved his antique seat, which had zero energy-absorbing capabilities, and was contemptuous of the HANS device when it first appeared.

But in the wake of his death NASCAR reacted, creating the ‘Car of Tomorrow’ which features some crushable structures, a more central driving position and redesigned rollcage. Massive changes were also mandated to drivers’ seats, with Formula 1 and Indy-style carbon seats superseding the ancient devices used by Earnhardt and his peers through the turn of the century. And slowly but surely NASCAR and its drivers grew to appreciate and adopt the HANS device.

Another part of Earnhardt’s legacy is NASCAR’s huge market in souvenir sales. Back in 1985 Earnhardt was the first driver to bring a souvenir trailer to the track to sell Wrangler Jeans-branded Dale Earnhardt baseball caps, T-shirt and jackets. As his career boomed so did sales, and other drivers and teams followed suit. In 1995 Earnhardt hired Don Hawk to run his business affairs and Earnhardt-licensed souvenir and merchandise sales shot up to $40 million per year. In ’97 Forbes magazine estimated his income at US$19m, including $15m from endorsements and souvenir sales, the third-highest in the world of sport behind only basketball superstar Michael Jordan and golf sensation Tiger Woods. By the time he died, Earnhardt had purchased his own seat on the New York Stock Exchange and Dale Earnhardt Inc was reckoned to generate more than $100m per year in revenue.

Today Dale Earnhardt Jr is by far NASCAR’s most popular driver, even though he’s never won a championship or come close to equalling his father’s record of accomplishments. But Dale Jr is loved by NASCAR fans because he’s an unadorned Southern boy who talks and lives in the spirit of his father. Like his father, Dale Jr sells more souvenirs than any other driver, controlling more than a quarter of NASCAR’s merchandising sales. Ten years after his death the long shadow Dale Earnhardt cast across NASCAR looks set to linger for many years. Richard Petty won as many titles and many more races than Earnhardt, making him NASCAR’s unofficial king. But Earnhardt will rule forever as the heart and soul of American stock car racing.