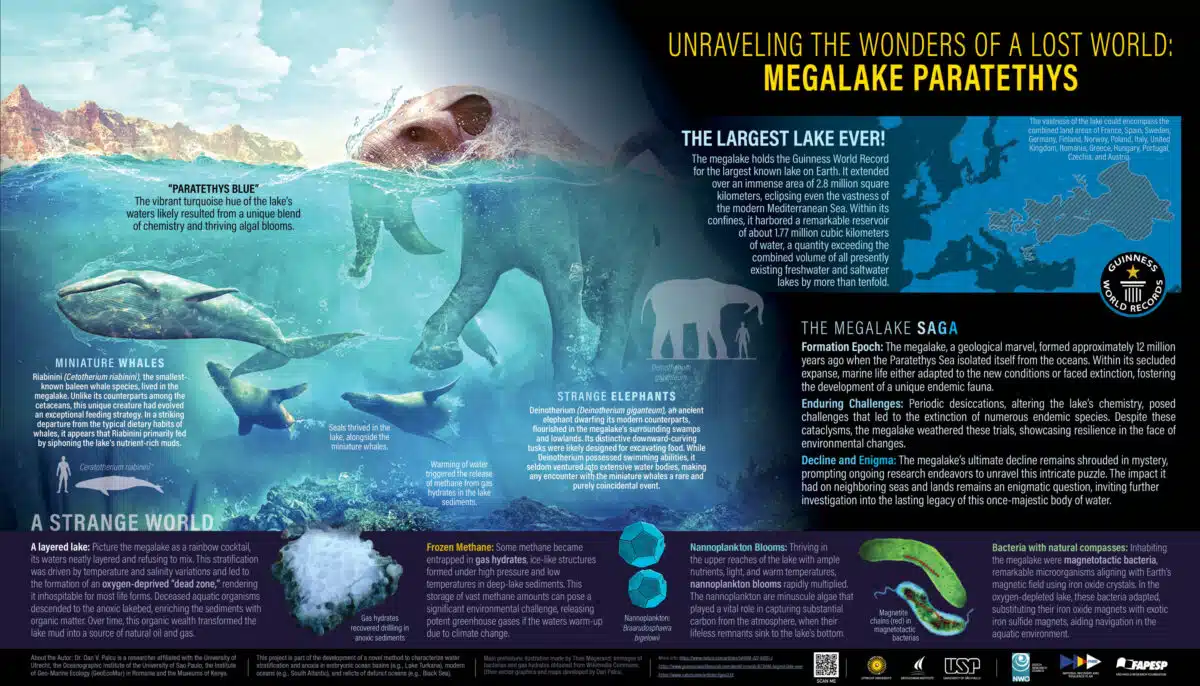

Twelve million years ago, a collision of continental plates in Central Europe gave rise to more than mountain ranges—it birthed Paratethys, the largest lake Earth has ever known. Spanning millions of square kilometers and holding more water than all lakes today combined, this prehistoric inland sea left a profound mark on evolution before vanishing forever.

Two new studies reported by Science reveal how this massive water body, formed by shifting geographies, repeatedly shrank and refilled, dramatically transforming the climate, wildlife, and even the landscapes across Europe and Western Asia.

From Tectonic Upheaval to Inland Sea

Paratethys began as a byproduct of tectonic activity that reshaped Europe’s center some 12 million years ago. When landmasses collided, they didn’t just build new elevations—they carved out a vast inland depression that would soon fill with water, creating a lake so large it covered over 2.8 million square kilometers. For scale, that’s more area than today’s Mediterranean Sea, according to research published in Scientific Reports.

At its peak, Paratethys held more than 1.77 million cubic kilometers of water, making it the most voluminous lake in Earth’s history. And it wasn’t just the size that stood out—Paratethys was effectively cut off from oceans, evolving as an isolated aquatic world, which in turn led to a wave of unique species appearing within its waters.

At its maximum spread, the megalake Paratethys (shown on modern geography) reached from the eastern Alps clear to Kazakhstan. Credit: Dan Palcu/Natural Earth.

At its maximum spread, the megalake Paratethys (shown on modern geography) reached from the eastern Alps clear to Kazakhstan. Credit: Dan Palcu/Natural Earth.

A Changing Lake With Devastating Consequences

This megalake didn’t remain stable. Climate variations triggered at least four major drying events during its 5-million-year lifespan. These episodes slashed the lake’s volume and surface area, with the most severe contraction, between 7.9 and 7.65 million years ago, dropping water levels by as much as 250 meters, according to paleo-oceanographer Dan Palcu and his colleagues at the University of São Paulo.

“Our exploration of the Paratethys goes beyond mere curiosity. It unveils an ecosystem acutely responsive to climate fluctuations. By exploring the cataclysms that this ancient megalake endured as a result of climate shifts, we gain invaluable insights that can elucidate the path to addressing current and future crises in toxic seas, such as the Black Sea,” he said.

This killed off much of the native plankton and algae. Species that couldn’t handle the salt died out, while others, like certain mollusks, survived and recolonized the waters when conditions improved, as noted in the same studies.

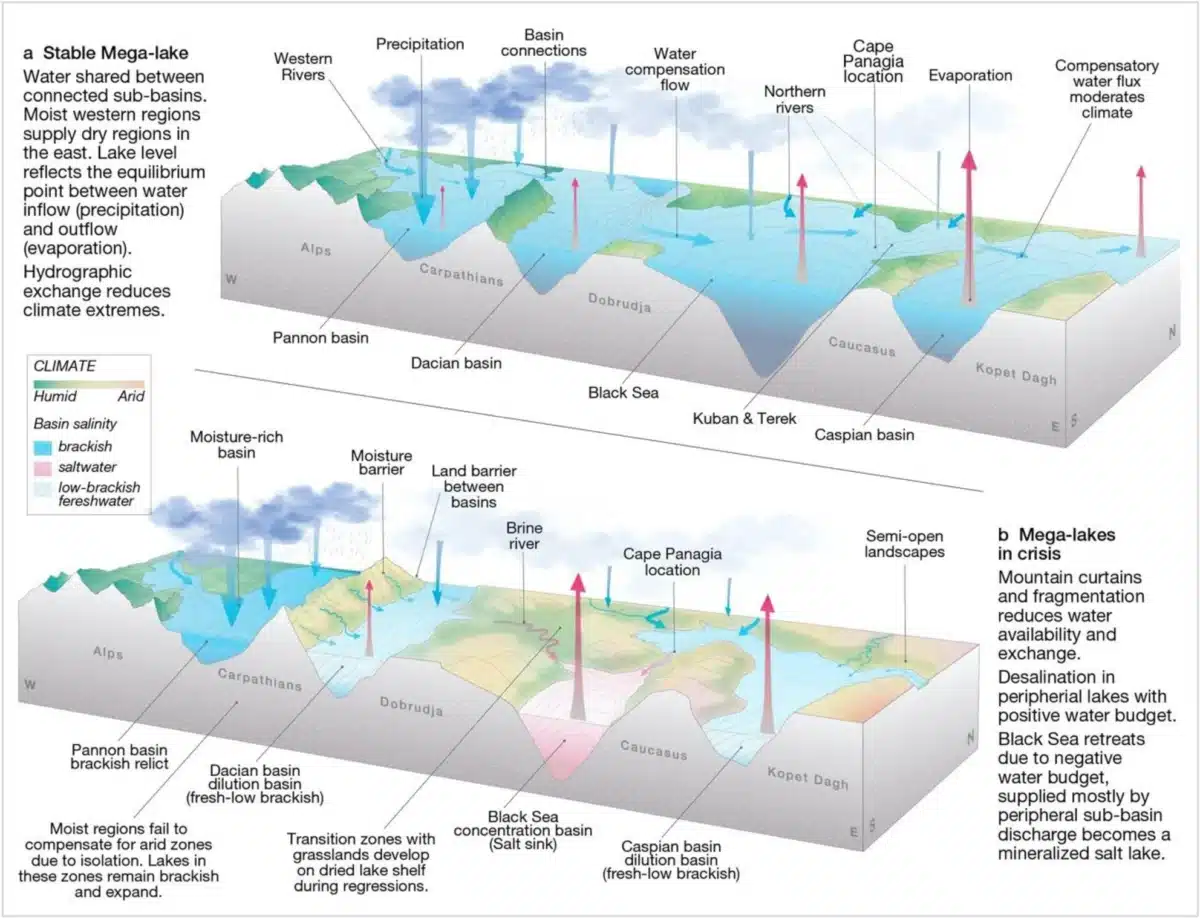

A model illustrating how wet and dry climate phases affected the Paratethys, a closed lake system disconnected from the ocean. Credit: Scientific Reports

A model illustrating how wet and dry climate phases affected the Paratethys, a closed lake system disconnected from the ocean. Credit: Scientific Reports

Home to the Smallest Whales and a Cradle for Giants

In its heyday, Paratethys was home to an unusual cast of aquatic life. The most striking were its miniature marine mammals. As noted by Science, many whales, dolphins, and seals living in the lake were dwarf versions of their ocean-dwelling relatives. The smallest known whale in the fossil record, Cetotherium riabinini, measured about 3 meters, shorter than today’s bottlenose dolphin.

But while the shrinking lake may have driven some species toward smaller forms, it also helped shape life on land. As Paratethys receded, vast stretches of new grassland emerged. Madelaine Böhme from the University of Tübingen explained that these grasslands became evolutionary hotbeds. In the north, ancestors of modern sheep and goats appeared. In the south, early relatives of today’s giraffes and elephants roamed.

If Paratethys existed today, our world map would look totally different. And so would our ecosystems. Credit: Utrecht University

If Paratethys existed today, our world map would look totally different. And so would our ecosystems. Credit: Utrecht University

The Last Outflow, and What It Left Behind

In the end, Paratethys didn’t just dry up—it drained out. Somewhere between 6.7 and 6.9 million years ago, a natural outlet opened up along its southwestern edge, probably under what we now know as the Aegean Sea. That break let the water pour out toward the Mediterranean, possibly creating a massive, roaring waterfall in the process.

Just like that, the world’s biggest lake was gone. But its story didn’t end there. The animals that had adapted to its shores and waters didn’t vanish, they spread out, with descendants that still live across Eurasia and Africa.