Engineers have taken another big step towards creating a quantum internet by linking two quantum processors so that several atomic connections share entanglement at the same time, not just one after another.

The team also found a way to treat differences between individual atoms as channels, which speeds up the rate of information sharing between nodes.

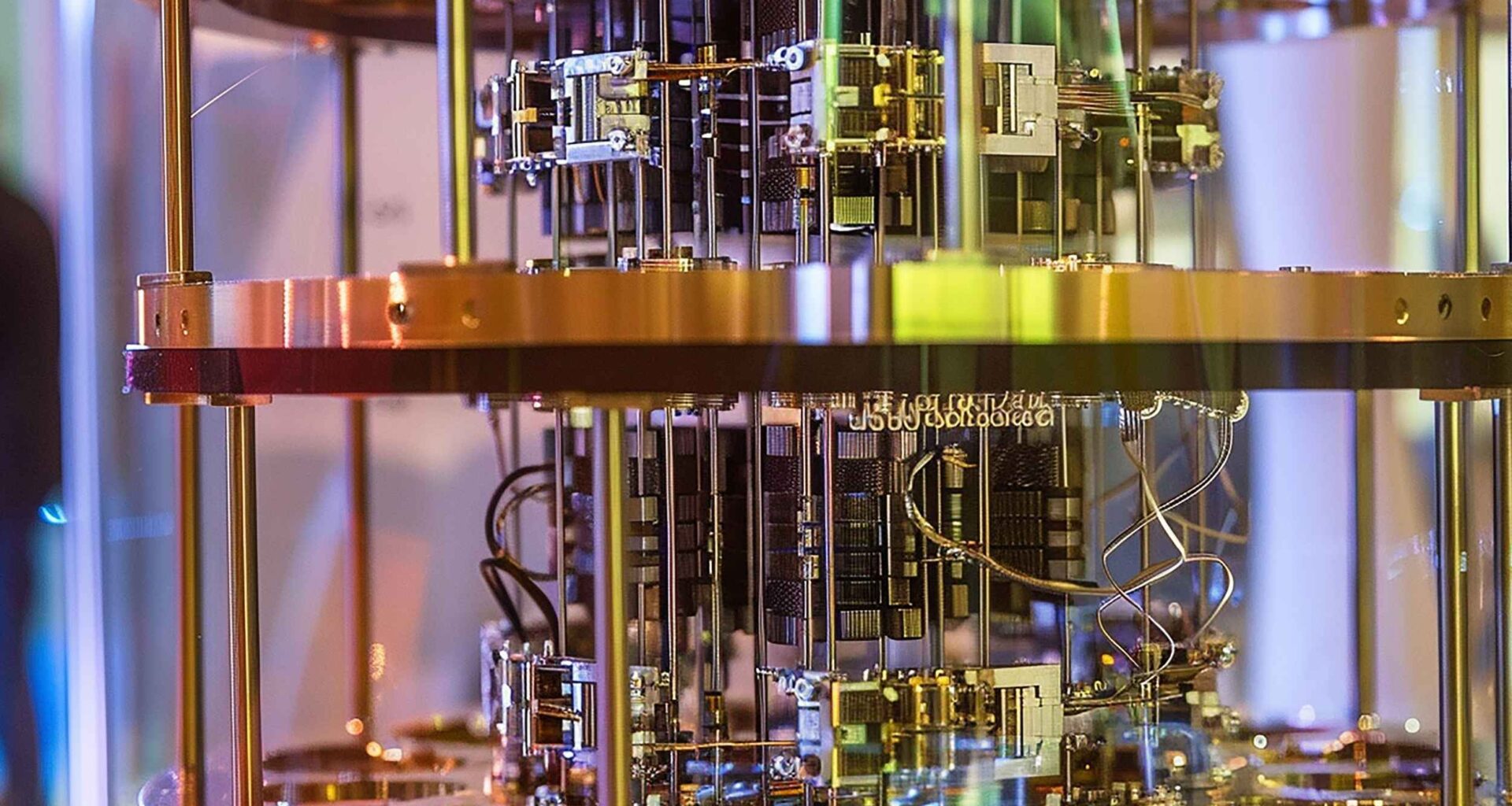

This early network lives on two nanofabricated chips in a lab, yet it hints at secure long-distance quantum links.

Building a quantum internet

The work was led by Andrei Faraon, the William L. Valentine Professor of Applied Physics and Electrical Engineering at California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

His research focuses on using tiny optical devices to connect single atoms that act as long-lived carriers of quantum information.

Long-term plans for a quantum internet imagine networks of devices that send fragile quantum states between cities and even continents.

That phrase means, a system that moves quantum information securely across long-distances and could support new kinds of encryption and distributed computing.

In the Caltech experiment, each node is a tiny chip that hosts many ytterbium atoms acting as individual qubits, a tiny quantum bit that can be 0 and 1 together.

To share information, the nodes try to place selected qubits into shared quantum states so that measuring one reveals something about its partner.

This work introduces entanglement multiplexing, a strategy that uses many qubits in parallel so several entangled links can be created at once.

Multiplexing and entanglement

Previous experimental quantum links usually relied on one optically addressed qubit in each node, so every attempt to create entanglement ran by itself.

That design made the overall communication rate painfully slow because the system spent most of its time preparing and resetting a single microscopic memory.

“This is the first-ever demonstration of entanglement multiplexing in a quantum network of individual spin qubits,” said Faraon. This method significantly boosts quantum communication rates between nodes, representing a major leap in the field.

In experiments, the team sent photons from two-nodes to a central station and used detection events to decide which pair should become entangled.

These results, including higher entanglement rates from several ions per node, are presented in a recent paper on the two-node network.

“Entanglement multiplexing overcomes this bottleneck by using multiple qubits per processor, or node,” he said.

“By preparing qubits and transmitting photons simultaneously, the entanglement rate can be scaled proportionally to the number of qubits,” said Andrei Ruskuc of Harvard University.

Rare earth atoms in tiny light traps

To build the nodes, the Caltech team doped crystals with a special kind of atom known as a rare earth ion, a class of elements whose inner electrons interact weakly with their surroundings.

Because those electrons sit deep inside each ion, rare earth crystals can preserve quantum information longer than other solid-state platforms at comparable temperatures.

One experiment showed that a nanophotonic resonator in such a crystal can act as a chip-scale quantum memory for single photons.

In this setup, each node is carved into a nanophotonic cavity, a tiny structure that traps and guides light in a small region.

When a laser excites one embedded ytterbium ion, the cavity boosts its emission so the photon travels toward the central station.

Each node contains roughly twenty such ions, and tiny differences in the crystal environment give every one a slightly different optical color.

Those color differences once looked like a nuisance because photons with mismatched frequencies refuse to interfere in the right way to create entanglement.

Smart control for messy photons

The key trick in this work is a control method called quantum feed-forward control. That phrase means, changing later quantum steps based on detector timing.

During each attempt, detectors at the central station record when photons from the two-nodes arrive and which combination of sensors clicked.

The control system turns that timing pattern into rotations on the relevant ions so their shared state always has the desired entangled form.

Beyond simple pairs, the team also prepared a special three ion W state, an entangled pattern where one shared excitation spans several particles.

Such multipartite states are harder to create than pairs, yet they are useful for tasks like secret routing or distributing work among quantum nodes.

The ability to make W states on demand with hardware that produces pairwise links suggests versatile network nodes rather than single-purpose devices.

Next quantum internet steps

Looking beyond this single experiment, theorists have outlined architectures for a quantum network that links many nodes using repeaters, memories, and light-based connections.

That phrase means, a collection of quantum devices linked by channels that carry entangled particles, and schemes for building such networks are surveyed elsewhere.

Most earlier test bed links relied on one optically addressable qubit per node, which limited memory capacity and the rate of successful entanglement.

They showed that many distinguishable ions in one cavity can act as separate channels, hinting at on-chip repeaters built from the same hardware.

In this platform, simulations suggest that a single node could eventually host hundreds of useful qubits.

If engineers also convert the emitted photons to telecom wavelengths, signals from such nodes could travel many miles through optical fiber with moderate loss.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–