Rebecca Clarren’s two young children accompanied her to the Black Hills as she did the reporting for her book. “You can be a child and have the capacity to hold multiple truths at once,” she says. “They understand that we can be proud that we descend from homesteaders, and we can realize that the taking of Native land and giving it to white people was immoral…” Photo by: Shelby Brakken, courtesy Rebecca Clarren

Rebecca Clarren’s two young children accompanied her to the Black Hills as she did the reporting for her book. “You can be a child and have the capacity to hold multiple truths at once,” she says. “They understand that we can be proud that we descend from homesteaders, and we can realize that the taking of Native land and giving it to white people was immoral…” Photo by: Shelby Brakken, courtesy Rebecca Clarren

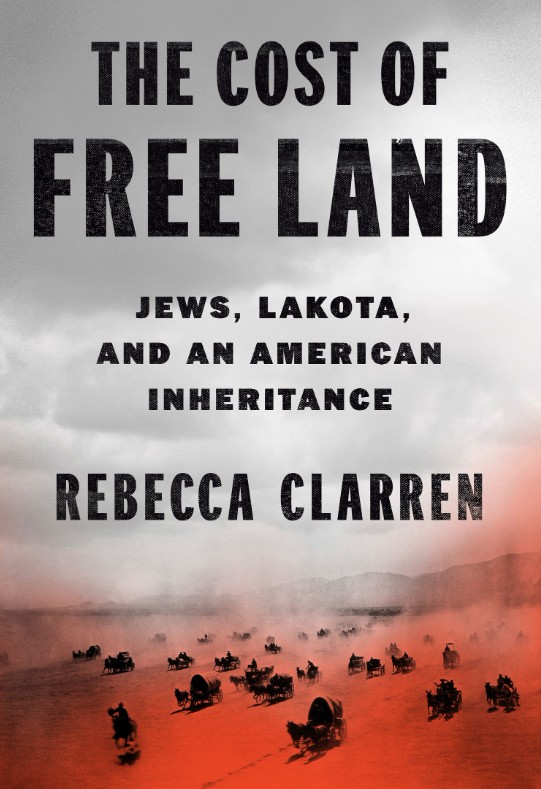

Rebecca Clarren, author of The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance, won the Frances Fuller Victor Award for General Nonfiction at the 2025 Oregon Book Awards ceremony this spring. Originally from Seattle, the journalist and author returned to the Pacific Northwest in 2002 after reporting on environmental and economic issues for Colorado’s High Country News, making Oregon her home.

“I moved to Portland in part because it was so much more affordable than Seattle,” Clarren told me over the phone. “It just seemed to me at the time, and still feels to me to this day, like a very interesting, vibrant place for a creative person to live. I moved here and started freelancing and was able to have enough success.”

Clarren attended Smith College, studying anthropology and studio art, before transitioning to writing for national magazines, at one point also writing a column for The Oregonian. Her novel, the Colorado-set Kickdown, was released in 2018; The Washington Post called it a “moving evocation of a place and a people and a way of life at a pivotal point in our history.”

“I always thought I would be a fiction writer because I loved fiction so much, and I initially really didn’t write much at all in terms of journalism. I didn’t write for my college paper and wrote a tiny bit for my high school paper,” Clarren said. “When I graduated from college, I was working as a maid in Alaska and realized I did not want to continue working as a maid. I had this insight, which is strange to me how right it was, but I just thought, You know, I should try being a journalist. I love traveling, I love meeting new people, I’m super curious, and I like writing. So, that’s when I decided to try becoming a journalist. And I’m so grateful, because that was a great instinct. It’s been such a good job for me.”

Throughout her career, Clarren’s passion for topics that hit close to home has been a driving force behind her work. She has written investigative stories about the American West for High Country News, InvestigateWest, and Indian Country Today, focusing on the dangers of oil wells, education crises, the consequences of mass logging, company greenwashing, and more. In The Cost of Free Land, Clarren unpacks a complex family history intertwined with the land and rights of the Lakota Indigenous peoples. Through research and a deep dive into her relatives’ pasts, she uncovers and tells a story of persecution, resilience, inheritance, and landscape.

Clarren and I talked about her career’s unconventional path, maintaining a writing practice while raising young children, and the journey and success of her acclaimed book. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

***

Sponsor

When did you first start writing, and what genre did you begin writing in?

I feel like I have always identified as a person who loves writing and reading. I was a voracious reader as a child — I am to this day; I have memories of being around 7 or 8, when my friend, Sarah, and I would make little books and go door-to-door to try to sell them in the neighborhood.

When I first had that insight, I thought I’d have to go to graduate school because I had no experience. A distant relative was an editor at The New York Times, and he was so kind as to tell me not to go to journalism school. He told me that school would have given me contacts, but there are other ways to get contacts. He urged me to just sort of put myself in the room, to literally walk into a newsroom and ask for a chance, which I ended up doing in Colorado in 1998. I went to the Durango Herald, which is a wonderful small-town newspaper that still exists. They couldn’t give me a job, but they let me start freelancing, and that writing led me to get a job at High Country News.

You write nonfiction, fiction, and poetry. Can you talk about how these genres intersect?

Poetry is relatively new to me. During the pandemic, when I was working on The Cost of Free Land, I started talking with a good friend whom I had met at a book festival. She and I have a lot of common interests, and she was writing a lot of poetry. She convinced me to take poetry classes with her through Hugo House out of Seattle, and I realized how much I loved writing poetry. At one point, I was talking to my friend Alicia Jo Rabins, who is an incredible local poet and writer, and I said, “Why am I writing these bad poems? What am I doing?” And she said, “You’re cross-training. When you run a marathon, you don’t just go running; you do other kinds of exercise. The Cost of Free Land is your marathon, and this poetry is helping your brain.”

I have learned to feel so much that that is true, that writing poetry reveals things I didn’t know about myself. I’ve been published in six or seven poetry journals, and that’s been wonderful. Mostly, it’s a sea of rejections on my Submittable pages. But I do feel even the poems that ultimately have not been published, I often am gutting for the good lines and using those lines in my nonfiction.

I taught a class at one point called “The Art of the Deeply Reported Novel.” I think that I use the same skills of research in my poetry and my fiction. The fiction has helped me think so much about narrative arc and structure, and the poetry helps me think about things at the line level. Before I wrote poetry, I don’t think I was as deeply connected to the sentence and the feeling tone of writing. So I’m grateful to be trying to do them all, though I don’t know if I will ever write another novel. I found it so hard.

Sponsor

What was the novel-writing process like for you on your first book, Kickdown?

Humbling. You know, I didn’t go to journalism school, so my thought process was, No one taught me how to be a journalist. No one needs to teach me how to be a novelist. I’ll just figure it out. And one could read the book and decide if I figured it out well enough.

The process was writing a draft and realizing it wasn’t good enough, and rewriting. I rewrote the entire book four times before it was good enough to show to a publisher. So it was kind of an agonizing process of trying to do it.

When I was pregnant and had my babies, I couldn’t really figure out how to be a journalist and be on deadline, so writing a novel when I was having really little kids was also a wonderful thing to be doing, because it felt like my own thing. I still had a place in my mind to go that was mine, even when I was in it with the littles.

Was that partially the catalyst for writing your most recent book? What brought you to the idea?

It really had nothing to do with Kickdown, actually. Before it was even published, I ended up getting a job through an investigative nonprofit journalism organization called InvestigateWest. They hired me in 2017 to write a series of stories about how federal policy has and is impacting Native nations, Indigenous families, and communities. And there’s this newish, evolving model for how to do investigative journalism, which is really wonderful. It’s collaborative. As I was hired to do the work, we partnered with The Nation and Indian Country Today, who then published the series and provided editing.

It was while working on that series of stories that I realized, Oh, OK, so I’m showing and trying to expose the harms of these federal actions, but my family benefited from the same policies that have been so harmful to Indigenous communities, because my family were homesteaders. There was this sort of slow-dawning realization that led me to think, What if I tried to write a book of entangled histories that showed how federal policy played out so differently on the same land, the same South Dakota prairie, but on two sides of this invisible wall demarcating the reservation?

Sponsor

Was it hard for you to write about your family history?

It was a lot of things, and it was so fantastic. I’m lucky that I got paid to do family research, and I loved all the things I got to learn — and it was painful. It was also hard. There’s something I say in the book, “What are the stories we tell, and what are the stories we don’t tell? And why don’t we tell certain stories?”

That deep investigation into the myth-making on my own family level… It’s hard to suddenly see your relatives more clearly for who they were than the stories that have always been told about them. They are beautiful people, and there is more to their complex stories.

How long was the whole process from start to publication?

I got a RACC [Regional Arts & Culture Council] grant to help me do initial research. I was given that in October 2018, and the book came out in October 2023. That was the full timeline. Of course, there were a lot of things going on at the same time. My novel came out in fall 2018, so I didn’t really start working on the next book until the following year. Then, I got a book deal in the fall of 2019.

What was it like working on it during the pandemic?

It was so hard and not ideal, but that deep constraint led me to do things differently than I would have done. I’m grateful for some of those things. For example, to really show how my family benefited from being homesteaders, I wanted to pull every land record that exists and also pull every mortgage that my family took out on our land before the pandemic. I’m a pretty micromanaging reporter, so I would have felt like I had to spend days alone in the Register of Deeds office in Rapid City doing that work, but due to the pandemic, I couldn’t. I ended up hiring this fantastic person who has an advanced degree in history, and she pulled all the records and made Excel spreadsheets for me.

Sponsor

I also ended up having a lot of phone calls. I probably would have gone in person more, but I couldn’t. I had phone calls with Lakota elder Doug White Bull, and with my Aunt Etta. It was a way to feel deeply connected during an isolating time.

Instead of flying to do research, my family rented a minivan and drove from Portland to the Black Hills and camped along the way. My kids were 5 and 8 when we did that. It’s amazing to me that we did it, in retrospect, but it was fantastic.

Did your kids have an understanding of what you were doing and working on?

Oh, yeah, for sure. We talked about it and continue to talk about it a lot, and they’ve come with me to many events. At this point, they’re 10 and 13, and I feel like they have the capacity [to understand]. They show me that you can be a child and have the capacity to hold multiple truths at once. They understand that we can be proud that we descend from homesteaders, and we can realize that the taking of Native land and giving it to white people was immoral, and we can think about how we might repair that today. And that doesn’t feel like a heavy burden, the way they talk about it. It’s been neat to be in that with them.

Does your Jewish identity play a larger role in your work as a whole? What was its the role in the context of The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance?

My Jewish identity is certainly at the center of this book. I would also say I live in the West, and I’ve always lived in the West, and I remember writing an essay as a young reporter about being Jewish in a rural town. It’s not something that I’ve hidden, and certainly there are many Jewish themes in many of my poems, but it has not been central.

Who are some of your favorite writers that you recommend to others?

Sponsor

I have so many people, and could go on and on. I always hope that if I’m just in the same cul-de-sac as Joan Didion — that would be great. Louise Erdrich has always been a really big influence on me. Her novels are so fascinating, and I admire her depths of reach into a subject, especially the way she writes from many different voices’ perspectives.

I recently read Martyr by Kaveh Akbar, and thought it was just deliriously, surprisingly fantastic. There are also so many incredible Indigenous writers who are working — everyone from Ella Deloria, whose work is from half a century ago, to Tommy Orange.

What advice can you offer new freelance journalists who want to get published or enter investigative journalism?

There are so many things to say. First, this can be a lonely job, so I would advise creating community in two different ways. One is finding the other writers who are doing the same kind of writing. That’s been invaluable to me — to have a semi-regular group — and it’s not necessarily that we’re reading each other’s work, although, when I was writing fiction and when I’m writing poetry, I am in groups with people whose work I really admire. With nonfiction, it’s great to just meet and talk upstream of the writing… “How do you pitch this person? What’s a good idea? What’s the right angle?” I think it is a great thing to have community.

On the other side, I always have, in my mind, formed an unofficial advisory board to my work, and they are the people out in the world who are way smarter than me. They are in the thick of whatever kind of topics I want to report on. They are who I call up every once in a while and say, “What are stories that you think are important that aren’t getting enough attention?”

I think I’m only ever as good as what work I’m reading. So I always try and read really excellent fiction and nonfiction, because I find that those voices in my head help my writing improve.

I also would say, try to be really prepared for interviews, and if you’re just starting out, try and figure out a topic that you’re really interested in, that you feel like you’re well-positioned to be writing about. For example, when I left High Country News, I suddenly understood a lot about the American West. I understood what the National Environmental Policy Act was. So, when I left to be a freelancer, it made sense for me just to continue to write about the American rural West for magazines. There weren’t a lot of people also wanting to write those stories. I think that’s really helped me have a freelance career. Finding your niche and your lane is helpful, especially at first.

Sponsor

Is there anything else that you want readers to know?

Support independent bookstores. This is such an amazing literary community that we have here. It’s so special, it doesn’t exist everywhere, and I don’t want us to take it for granted. We have such support for the literary arts and much access to free readings and events in this town. It’s all around you. Just find it, seek it out.