Shannon Marshall spent 10 months in the Harris County Jail in 2000, awaiting a capital murder trial and eventual transport to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Marshall, who would go on to spend a quarter of a century in Texas prisons, said his days at the Harris County Jail were some of the most terrifying of his life.

“Do the crime, do the time” is a common refrain among those who aren’t particularly worried about whether Texas inmates are provided timely medical care or nutritious meals. “It’s not supposed to be Club Med,” they say.

But inmates are also not supposed to die while in custody on the taxpayers’ dime, says Ashleen Gaddy, an advocate and founder of Heart Check Prison Strategies Group. Gaddy is dating Marshall, who was released from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice in November. Gaddy’s son is currently incarcerated and was housed at the Harris County Jail in 2021 and 2022.

Three Harris County Jail inmates died in custody within a 48-hour period last month. While the circumstances surrounding their deaths are unknown pending autopsies, the news hit home for Marshall and Gaddy.

“It breaks you,” Gaddy said.

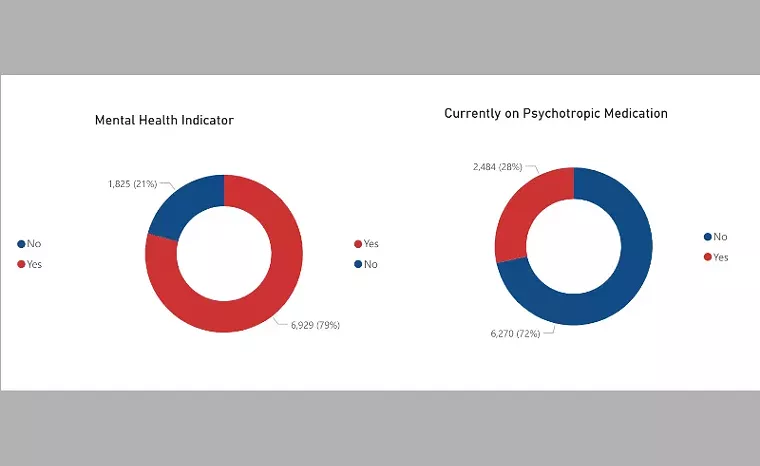

As of last week, Harris County’s jail population was 8,754, with more than 1,400 of those inmates outsourced to facilities in Louisiana and Mississippi. About 79 percent have a “mental health indicator,” and 28 percent are on psychotropic medication, according to the sheriff’s department dashboard.

Harris County Sheriff’s Department dashboard

Graphic by Harris County Sheriff’s Department

City and county jails in the Lone Star State are overseen by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, which mandates, among other things, “reasonable temperatures” between 65 and 85 degrees in occupied areas. The Commission has the ability to shut down a facility, but the Harris County Jail has been noncompliant for more than three years and remains operational because the county can’t afford to close such a large operation, says Krish Gundu, cofounder of the Texas Jail Project.

A notice of noncompliance issued by the Commission in January found that the jail was understaffed and face-to-face observations had not been conducted as required. A second notice issued in May found that an inmate did not receive a medical evaluation after submitting an emergency request.

“The medical staff was unable to conduct an assessment at that time due to the absence of the jailer assigned to triage,” the report states.

The family and friends of 35-year-old Ronald Erwin Pate, who died June 24 after being held at the county jail for less than two weeks, have said they want to see jail surveillance videos and medical records to understand what happened to their loved one. Civil rights attorney Randall Kallinen, who represents the family, asked for an investigation by the Texas Rangers or the FBI.

“We are experiencing a surge in jail deaths,” Kallinen said at a press conference. Ten inmate deaths have been reported thus far this year, matching the total number reported in 2024.

Alexander Winstel, 43, suffered a medical emergency inside the jail and was taken to St. Joseph Hospital, according to the sheriff’s department. He was previously diagnosed with a life-threatening health condition and was pronounced dead on June 22.

A third inmate, 68-year-old Phillip Brummett, 68, was pronounced dead at Ben Taub Hospital on June 22. Sheriff’s department officials said he was hospitalized after suffering a medical emergency in the jail a few days prior. Both Winstel and Brummett had been in custody for less than a week at the time of their deaths, which Gundu says is an indication that they shouldn’t have been jailed in the first place.

“The fact that two of them died within four days of being booked tells me that they were probably unfit for confinement when they came in,” she said. “They probably should have been sent to the hospital. Medical screening is one of the things they do during booking.”

Gaddy agreed. “I think they need to start properly evaluating people going in, and the kids and the adults that are truly mental health cases need to go to San Antonio State Hospital or mental health facilities that can properly deal with them,” she said. “If they’re claiming that they know these people have pre-existing conditions and days later they’re dead, that’s a breakdown in the intake process.”

Shannon Marshall, left, and Ashleen Gaddy advocated for criminal justice reform at the state capitol during the 89th legislative session.

Photo by Ashleen Gaddy

The Harris County Sheriff’s Department referred questions about medical care and mental health treatment to Harris Health. A spokeswoman for Harris Health declined to answer specific questions on the recent deaths but said individuals are screened at intake for medical and mental health needs and are referred to appropriate services accordingly.

“Persons in custody may self-report health information and/or providers may have access to their medical history in the Electronic Medical Record,” the spokeswoman said in an email. “Medical assessments of persons in custody are conducted in accordance with the standards set by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care and the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.”

Sheriff Ed Gonzales has said in the past that an “inefficient court system” is to blame for jail overcrowding and that the rising number of in-custody deaths can be attributed in part to an influx of inmates with pre-existing medical conditions. More personnel and resources are needed, the sheriff has said, and that funding has to come from the Harris County Commissioners Court.

“I just laugh when I hear pre-existing conditions. That’s what you hear all the time,” Gundu said. “Everybody has a pre-existing condition; it’s called life. It’s an easy excuse.”

Sheriff’s Department Senior Policy and Communications Advisor Jason Spencer said the jail currently has 148 detention officer vacancies.

“We are on track to start a new detention officer training class at our academy for 55 to 60 new hires on July 21 and another similarly sized class on August 18,” he said. “At our current pace of hiring and attrition, we expect to be fully staffed sometime this fall, at which time we intend to request Commissioners Court approval for 200 more detention officer positions.”

Harris County and Gonzales are named in several lawsuits, Gundu said, some of which allege medical neglect, violence, or failure to comply with Texas’ mandated detention officer ratio. Gonzales did not respond to an interview request.

Spencer referred some questions regarding the in-custody deaths to an online reporting system that offers limited information. All three of the June deaths are pending autopsy and are under investigation by the Houston Police Department, “in accordance with a state law that requires all jail deaths to be investigated by an outside law enforcement agency.”

“The Sheriff’s Office Internal Affairs Division is also investigating to determine whether all applicable policies and procedures were followed, which is standard following the death of a person in jail,” the website states in relation to each of the June inmate deaths.

Gundu said in-custody deaths at the Harris County Jail are not breaking news. This has been going on for years. At least 22 people died while in Harris County Jail custody in 2022, Gundu reported for Slate.

No one seems particularly concerned that the county jail on San Jacinto Street has been out of compliance for years, Gundu said.

“One would think that if a jail is noncompliant, that there would be some efforts to shut it down, which is what would happen if it were a small enough jail,” she said. “This is just too big of an operation. We’re really frustrated, and there’s no real plan from the county to remedy any of the things that are causing these deaths.

“We don’t even really know what is causing the deaths,” she added. “There is no transparency and no accountability. We don’t know what is happening in there.”

Spencer confirmed in an email that the Harris County Jail is on the Commission’s list of noncompliant facilities but offered no information as to what’s being done to change that.

Mental Health Crisis

Many advocates hoped to see sweeping changes when new District Attorney Sean Teare took office in January, promising to swiftly dispose of a backlog created during the COVID-19 pandemic when courts were shut down. Teare also favors mental health and substance use treatment programs when appropriate and has said he wants to reduce the number of nuisance crimes that are prosecuted.

“Since taking office in January, the Teare Administration has prioritized breaking the cycle of crime by surging resources toward programs that work to prevent and treat the root causes of criminal behavior,” a spokesman for the DA’s office said in an email. “Early efforts are paying off with a 9.5 percent drop in the jail population.”

The Harris County Commissioners Court approved in April an emergency $7.6 million allocation for the DA’s office to bolster a team of prosecutors and support new mental health and domestic violence initiatives. That includes hiring 15 new positions for the Mental Health Bureau, the spokesman said.

Additionally, more than 342 people with mental health disorders have been diverted into treatment instead of jail since Teare took office, and more than 230 cases have been tried so far this year, including 145 felonies.

The attention to Harris County’s mental health crisis is too late for Citterece McGregor. She testified before the Texas Commission on Jail Standards in May that her son, former University of Houston football player Kristopher McGregor, was admitted to the Harris County Jail with severe schizophrenia.

Medical records showed that Kristopher McGregor was taken to the hospital in septic shock from a strep throat infection, his mother said. He was not given proper treatment and starved to death, she added. The 39-year-old died in January, after being housed at the jail for less than a month.

“How can Harris County be so numb to mental health issues?” she said. “My son was jailed for a nonviolent misdemeanor charge. He died a preventable death.” Gaddy said her son was required to take the antipsychotic medication Seroquel while he was in county jail, even though he hadn’t been diagnosed with a medical condition, and he was shipped to Louisiana twice due to jail overcrowding. While in Louisiana, he was held down by other inmates who tattooed his face.

Gaddy was working as a paralegal at the time and said the experience led her to an advocacy career.

“My son had never been in trouble like that,” she said. “I felt helpless. I developed extreme anxiety disorders. I didn’t sleep at night. I was stuck in a constant fight-or-flight moment. I had to learn really quickly how to navigate the system. It was terrifying for me.”

The case of Simon Peter Douglas, who died by suicide in the Harris County Jail in 2022, is haunting, Gundu said. “He was brought in on a criminal trespass charge in acute psychosis, pretty severe psychosis,” she said. Douglas was self-harming and was eventually placed in a padded cell.

“In that cell, with restraints on, Simon managed to kill himself by hitting his head continuously on the metal grate on the floor,” she said. “[Jail staff was] doing observation rounds and basically just watched him die instead of getting him to the ER.

“When I got the investigation report from the jail commission, it said there was no violation of minimum standards, that they were doing their checks and all that. What is the fucking point of doing checks if you’re just watching someone kill themselves?”

Gundu doesn’t have the answer to that question, but she can answer why law-abiding residents should care about what’s happening at the Harris County Jail. For one, their tax dollars are paying to house more than 8,000 inmates. Secondly, she says, the mental health crisis has become a public safety issue.

“The jail is the largest warehouse of people with mental illness in the state of Texas,” she said. “That’s because, for about 18 years, the state has not funded a meaningful continuum of care for mental health. It almost seems deliberate, given the cases we see. We see people cycling through over and over again, dozens of misdemeanors and then a felony happens or God forbid a victim has been created.

“When you see an unhoused person on the street, you should care because that is a public health issue that is going to become a public safety issue,” she added. “If people’s basic needs are not met, it is going to ripple out. The jail releases people with serious mental health issues with no medication and no follow-up.”

The capital murder trial of Houston rapper Tavores Henderson, charged in the 2019 death of a law enforcement officer, is set to begin this summer. Gundu said Henderson has suffered from schizophrenia since he was 8 years old. His mother allegedly pleaded with hospital personnel not to release him during a psychotic episode, but they did anyway, and later that day, the vehicle accident that led to Henderson’s murder charge occurred.

“Whose fault is this? This is not an outlier; this is not a unicorn,” Gundu said, as she detailed other cases of those in mental health crises who have been jailed instead of hospitalized.

What Needs to Change?

A lot must be done to solve the litany of problems at the Harris County Jail, Gundu said. The outsourcing contracts with Louisiana and Mississippi are up for review at the end of the year and should be canceled, forcing Harris County to reduce its inmate population and move people through the system faster, she said. Harris County spends about $54 million per year to house inmates outside of Texas, according to reports.

“You paid for those beds, so they’re going to keep filling those beds,” Gundu said. “No amount of reducing the jail population is going to help until we look at those contracts.”

Marshall, the former Harris County inmate who now works as an industrial electrician near Fort Worth, said many incarcerated persons experience trauma, although they may not have diagnosed mental health conditions.

Back in 2000, Marshall faced capital murder charges because he was present when his friend shot and killed a man. The charge was later reduced to murder, and he was sentenced to 35 years, but at the time, he was facing life in prison or death, and he was still a teenager.

“I turned 18 years old in Harris County Jail,” he said. “I was in a so-called youngster tank for anyone under 21, and the youngster tanks were really rowdy, really violent, and very gang-related.”

He was on the seventh floor at 701 N. San Jacinto, in what was referred to as the “gladiator tank.” There, the young man said he saw several African American people with splotches of pink on their faces. He later realized they’d been burned by other inmates.

“They would take Magic Shave and any type of candy bar that had caramel in it, and they would put that in the boiling hot pot and would dash you across the face with it,” Marshall said. “The caramel sticks to your skin. Your natural instinct is to grab your face. When you grab your face and try to wipe your face off, you’re literally wiping the skin off your face. That’s what goes on.”

The guards were feared, he added.

“I’ve seen a guard grab a man around the throat and lift his body off the floor, hanging in the air, and choke him out until he passes out and just drop him on the floor and leave him there and walk away,” he said. “They actually enjoyed, got sadistic pleasure, out of beating the hell out of inmates in there.”

Two Harris County jailers were indicted in May on charges of assaulting inmates. Reports revealed that, in both cases, the officers stayed on the job for two years and were not dismissed until criminal charges were filed.

Marshall acknowledged that his Harris County Jail experience was many years ago and the violence may have lessened since then, but as a teenager potentially facing a death sentence, he was already anxious and traumatized.

“I was under so much pressure,” he said. “I was already kind of messed up in my head.”

Once he got to prison, he was able to take classes and enroll in programs, something that was lacking at the Harris County Jail. County jails could benefit from “field ministers,” longtime inmates with good behavior who can walk around the unit and check on their peers, he said.

“They could let them know that there’s hope, and if they’re religious, that there’s God,” Marshall said. “Inmates will talk to inmates more readily than they will to an authority figure.”

Marshall and Gaddy say that through their newly formed LLC, they hope to bring training programs into county jails, probation offices, and schools to educate youth and reduce recidivism. Gaddy said that jails have traditionally been temporary detention centers for those who can’t make bail or are awaiting trial, so the mentality is, what’s the point in offering education or job training for people who might just be there a few days or weeks?

But in Harris County, many inmates stay in the holding pattern for years, some of whom ultimately have their cases dismissed, only to be released and find that they’ve lost their jobs and have no place to live. The average stay in Harris County Jail is about 177 days, according to the dashboard.

“There’s zero rehabilitation in county jails, and not all of [the inmates] are going to prison,” Gaddy said.