The origin of life is one big chemical Catch-22. It always has been.

To get life started, you need a genetic molecule—something like RNA or DNA. That’s needed to store information about how to replicate the cell and pass it along. But in modern cells, copying RNA and DNA requires proteins. Proteins, in turn, are encoded by genetic molecules. And neither can function without fatty lipids, which form the membranes that keep cells from dissolving back into the environment. Worse still, enzymes made of proteins are required to synthesize lipids in the first place.

It’s a biochemical ouroboros: everything needs everything else to exist.

This circular logic has made the origin of life seem almost magical, as if biology required a spark that chemistry alone couldn’t supply. But according to John Sutherland, a chemist at the University of Cambridge, that impression may be wrong. Life’s paradoxes, he argues, don’t require miracles—just the right chemistry, happening in the right places, at the right time.

The Chemistry That Leads to Biology

Sutherland is not a biologist by training. He’s an organic chemist, educated at Oxford, who drifted toward one of science’s hardest problems almost by accident. What drew him was the question of whether simple chemistry could plausibly generate the molecules biology depends on.

That question led to a breakthrough in 2009, when Sutherland and his colleagues showed that key building blocks of RNA could form without enzymes, under conditions that might have existed on early Earth. The result gave new credibility to the RNA World hypothesis, which proposes that RNA came before DNA and proteins, acting both as genetic material and as a primitive catalyst.

But the work also drew criticism. The chemical precursors Sutherland used—acetylene and formaldehyde—were simpler than RNA, but still complex enough to raise an awkward question: Where did those come from? It’s the same circular game all over again.

Rather than defending the chemistry as-is, Sutherland and his team went backwards.

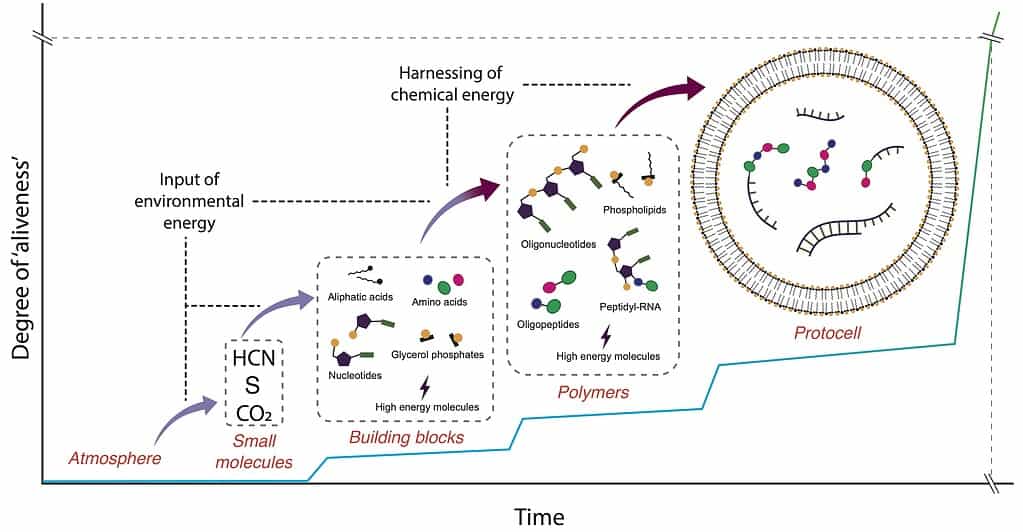

A schematic representation of different stages of molecular evolution during the transition from chemistry to biology. Credit: adapted from Sutherland (2017).

A schematic representation of different stages of molecular evolution during the transition from chemistry to biology. Credit: adapted from Sutherland (2017).

In a series of papers culminating in work published in 2015 in Nature Chemistry, Sutherland’s group demonstrated that you can start with a remarkably small set of ingredients—hydrogen cyanide (HCN), hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), ultraviolet light, and simple minerals—and end up with precursors not just to RNA, but also to amino acids and lipids.

In other words, the same basic geochemical environment could generate all three major classes of biomolecules required for life.

Hydrogen cyanide may sound like an odd candidate for life’s raw material. After all, it’s infamous as a poison. But that toxicity is a modern problem (modern by geological standards). Cyanide interferes with oxygen-based metabolism, and oxygen didn’t accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere until roughly two billion years ago. On the early Earth, cyanide would have been chemically active but biologically harmless, because biology as we know it didn’t yet exist.

More importantly, cyanide is chemically efficient. It contains carbon and nitrogen already bonded together, in just the right oxidation state to build complexity. Compared to carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas—the molecules modern biology laboriously fixes using elaborate protein machinery—cyanide is practically eager to react.

Sutherland’s work doesn’t claim that life sprang fully formed from a single pond or pool. In fact, he’s careful to argue the opposite.

The reactions that produce nucleic acid precursors, amino acids, and lipid components don’t require identical conditions. Some favor different metal catalysts; others need slightly different energy inputs. Early Earth, Sutherland suggests, was less like a single “primordial soup” and more like a patchwork of chemically related environments.

Rainwater, tides, and erosion would have transported molecules between these sites, pooling them together over time. The point is that chemistry didn’t have to get everything right in one place—it just had to get enough things right somewhere.

This view aligns with a growing emphasis on systems chemistry: the idea that life emerged not from one lucky reaction, but from networks of reactions reinforcing one another. Instead of trying to isolate a single “first molecule,” systems chemistry looks at how collections of molecules behave together—sometimes producing surprising order rather than chaos.

Ending Vitalism, One Experiment at a Time

Prof. John Sutherland. Credit: ZME Science.

Prof. John Sutherland. Credit: ZME Science.

In November, I caught up with Sutherland at the 2025 Falling Walls conference in Berlin. He told me he believes the field is approaching a moment when laboratories will be able to start with chemical mixtures that are obviously not alive and end, sometime later, with simple systems that show key hallmarks of life: compartmentalization, metabolism, and replication with variation. And at some point, someone will be able to make life from scratch in the lab, although he joked it probably won’t happen during my lifetime, so I won’t be able to bash his prediction.

If that happens, it won’t just be a technical achievement. It will mark the final collapse of vitalism—the old belief that living systems are animated by something fundamentally beyond chemistry. That idea took a major hit in the 19th century, when chemists learned to synthesize “organic” molecules like urea, Sutherland told me. But traces of it linger whenever life is treated as irreducible or exceptional.

Recreating the transition from chemistry to biology wouldn’t strip life of its wonder. It would deepen it—showing how something astonishing can arise from ordinary matter, given time and the right conditions.

Life Elsewhere, Life Otherwise

An artist’s conception of a Hycean exoplanet like K2-18b orbiting a red dwarf star 120 light-years from Earth. A repeated analysis of the exoplanet’s atmosphere suggests an abundance of a molecule that on Earth has only one known source: living organisms such as marine algae. Credit: A. Smith, N. Madhusudhan/University of Cambridge

An artist’s conception of a Hycean exoplanet like K2-18b orbiting a red dwarf star 120 light-years from Earth. A repeated analysis of the exoplanet’s atmosphere suggests an abundance of a molecule that on Earth has only one known source: living organisms such as marine algae. Credit: A. Smith, N. Madhusudhan/University of Cambridge

The implications extend far beyond Earth. If the chemistry Sutherland studies is robust—if it works whenever cyanide, sulfur, water, and energy coincide—then life may not be rare in the universe. It may be constrained, but common.

That possibility is already shaping collaborations between chemists and astronomers, who are trying to identify atmospheric “biosignatures” on distant exoplanets. Knowing which chemical pathways lead most naturally to life helps scientists decide what to look for—and what combinations of gases might signal biology rather than geology.

If life is found elsewhere, even once, the statistics change dramatically. Two independent origins would suggest that life is not a cosmic fluke, but a frequent outcome of planetary chemistry. And if that life shares our basic molecular toolkit, it would imply that chemistry itself funnels biology toward a narrow set of solutions.

None of this proves how life began. The crucial transition from molecular building blocks to self-sustaining, evolving systems remains unresolved, and may always be partly speculative.

But science doesn’t advance by eliminating mystery all at once. It advances by shrinking the gap between the known and the unknown.

What Sutherland and others have shown is that the origin of life no longer needs to hide behind paradox. The chicken-and-egg problems that once made biology seem impossible are giving way to something more interesting: a picture of early Earth as a chemically creative world.

Below you can read the transcript of my interview with Prof. Sutherland or watch the video version. The transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Interview Transcript

Tibi Puiu:

John, thank you so much for being here. For those who don’t know you or don’t follow your work closely, could you briefly introduce yourself and describe what you’re most known for?

Prof. John Sutherland:

I’m a chemist—an organic chemist. I trained in Oxford as a chemist, and over the years I became interested in the origin of life. I think we became known—although I don’t really like the word “successful”—because we managed to make nucleotides in a way which people hadn’t really thought of doing before, in a geochemical context relevant to the early Earth.

And that success really arose from collaborating with people outside chemistry, because chemistry on the early Earth isn’t isolated chemistry. It’s chemistry taking place on the surface of the Earth, and it helps if you understand the geochemistry. That’s essentially how we learned how to make nucleotides, and that’s what people tend to remember or recognize our work for.

Tibi Puiu:

The origin of life may be the biggest question in science. What do you think are the most likely explanations for how life first appeared? And what are the most important things people should keep in mind when thinking about this problem? How does this relate to your research?

Prof. John Sutherland:

One reason people were less successful in the past is that science education is often based in silos. There’s a silo of chemistry, a silo of geochemistry, planetary science, biology, and historically there was much less communication between them.

Of course, now there is much more collaboration, much more communication between people in those areas. The second thing I think was that people were limited by their ability to understand what had happened when they mixed things together, so their analysis was weak.

Modern chemistry has very advanced analytical tools, so we could probe more complex mixtures, and contrary to expectation when you make a mixture more complicated, it doesn’t necessarily produce more complex results.

Sometimes there’s a kind of simplicity that emerges in collections of molecules. We refer to this as systems chemistry. Studying isolated reactions isn’t enough for life—you need many reactions happening at the same time. People avoided that because they couldn’t analyze it and because they expected it would just make a mess. We’ve shown that if multiple reactions occur simultaneously, the outcome can actually be simpler than you might imagine.

Of course, that’s not enough on its own. You need to make the biological building blocks, then link them together into macromolecules. At some point, small and large molecules have to start using energy in an ordered way to replicate, with mutation, so errors are generated and the system can improve.

So I don’t think we’ve got to that point now but at least by understanding what the building blocks are, I think we’re better positioned than ever before to start dealing with that next phase.

Tibi Puiu:

And did everything go as planned when you embarked on this sort of quest? Were you surprised by your findings? You mentioned in today’s talk hydrogen cyanide. Can you expand a bit about that?

Prof. John Sutherland:

When I started, as a young man, I confidently expected that we’d understand how the building blocks were made within a couple of years. I’m now approaching the last quarter of my life, and we’ve almost finished making the building blocks. It’s taken much longer than we expected.

One reason is that it took time to work out what the key molecules on the early Earth might have been—what the feedstock molecules were. Biology today fixes carbon from carbon dioxide and nitrogen from nitrogen in the atmosphere. Either of those fixation events is extremely tricky and represents a masterpiece of biology.

Imagining that both of those were fixed early on in biology is incomprehensible. You can’t imagine that. But if you start with hydrogen cyanide, you have carbon and nitrogen in the same molecule, already in roughly the right oxidation state. Cyanide turns out to be very well set up to start making the molecules you need. If you instead use modern biology—starting from CO₂ and N₂—as your guide, you go badly wrong.

Tibi Puiu:

I think some people watching us are scratching their heads right now. Isn’t cyanide poison?

Prof. John Sutherland:

Yes, cyanide is a poison. It inhibits an enzyme called cytochrome c oxidase, which is the terminal enzyme in the respiratory chain—it’s responsible for passing electrons to oxygen.

Oxygen only appeared in Earth’s atmosphere about two billion years ago, during the Great Oxidation Event. Before that, there were no enzymes passing electrons to oxygen, so cyanide wouldn’t have been toxic. So we shouldn’t look at cyanide now and assume it was always toxic.

Tibi Puiu:

What do you reckon is the main barrier now in this line of research?

Prof. John Sutherland:

There’s the perennial barrier of funding—there are many pressures on governments and individuals to spend money on other pressing needs. But conceptually, the field is in a much better position now.

We know much better what the building blocks are. We have a clearer idea of what we’re aiming for: a protocell with replicating RNA, possibly with simple peptides synthesized at the same time. We’re also getting a better sense of what energy sources might have driven the process.

I would say we’re getting remarkably close to the point where someone will do an experiment where you start in a laboratory with a mixture of chemicals that is obviously not alive, and within a couple of weeks you end up with simple cells showing all the hallmarks of life.

That will be an extraordinary experiment. It will finally remove the last vestiges of vitalism—the idea that there’s something special about biology that means it can’t be recreated from chemistry. Wöhler’s synthesis of urea destroyed most of vitalism, but some elements still persist.

If we can demonstrate by experiment that we can kick-start biology just by mixing the appropriate chemicals in the right sequence in a way that simulates what happened on early Earth, that will dispel vitalism completely. Then we’ll have a rational explanation for how it all started and why we’re here.

Tibi Puiu:

So other research groups I’ve read about showed some semi-synthetic RNA, semi-synthetic DNA, even. I think recently someone reduced the number of codons in an E. coli bacterium. There are interesting developments in sort of synthetic life, if you can call it this way, but I think you raise a super interesting point: we can imagine some point in time in the future when some research group actually makes life from scratch. And I’m trying to imagine the implications of this. I mean, how will people cope with this?

Prof. John Sutherland:

You mentioned reducing the number of codons. Jason Chin, for example, has reduced the number of codons in E. coli down to 57 in the latest version, and that number will likely get lower.

What he’s doing is simplifying biology from the top down. Those of us working on the origin of life are approaching it from chemistry up. At some point, we hope those two approaches will intersect.

If you keep simplifying biology, you eventually reach systems with far fewer than 20 amino acids. We think we know what the first amino acids were, because they’re the ones we can make from our chemistry. It’s like tunneling under the English Channel from both sides—eventually the tunnels meet. It’s a very long tunnel, about 3.7 billion years of biological history, but humans are good at solving puzzles.

We’re not doing this just for fun. We’re doing it because we really believe it can be achieved. More and more people are working on this now because they can see that the end is in sight.

Tibi Puiu:

Finally, does your work inform the search for life on exoplanets? Should astronomers be looking for particular molecular signatures?

Prof. John Sutherland:

That’s a very thoughtful question, and it does connect directly to what we’re doing. There’s ongoing discussion between the chemistry community and the exoplanet community. In Cambridge, for example, I collaborate with people who study exoplanets and their atmospheres.

Chemists can suggest what astronomers might look for, and astronomers can tell chemists what they actually have a chance of seeing. We talk about biosignatures—gases, or combinations of gases, that might indicate life.

If life exists elsewhere, it might resemble Earth biology, which would suggest there’s only one solution. Or it might be different, which would suggest multiple solutions. Humans will create artificial life at some point, possibly superior in some respects to natural biology, which is constrained by the fact that it had to start on a rocky planet with a limited set of chemicals.

If life is found elsewhere, even once, it changes everything. If n equals two, then n almost certainly equals many more than two. And if that second form of life turns out to use the same chemistry as ours, with no possibility of panspermia, that would be a very strong indication that there may be only one way for life to start.

So I’m hugely in favor of these explorations. I think observations elsewhere may end up telling us more about our own chemistry than our chemistry tells us about them.