New York City’s medical examiner will begin offering free genetic testing to blood relatives of people who die suddenly from inherited conditions — a first-of-its-kind program that officials say could save lives.

The city’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner will launch the new Genetic Intervention Family Testing Services, or GIFTS, program in early 2026 and will screen living relatives for the same genetic conditions that killed their loved ones. It marks the first time a medical examiner’s office in the country will test living patients, city officials said.

“We’ve had the experience of families losing a second loved one to a genetic problem,” Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Jason Graham said in an interview. “While we deal with death every day, everything we do here is for the living.”

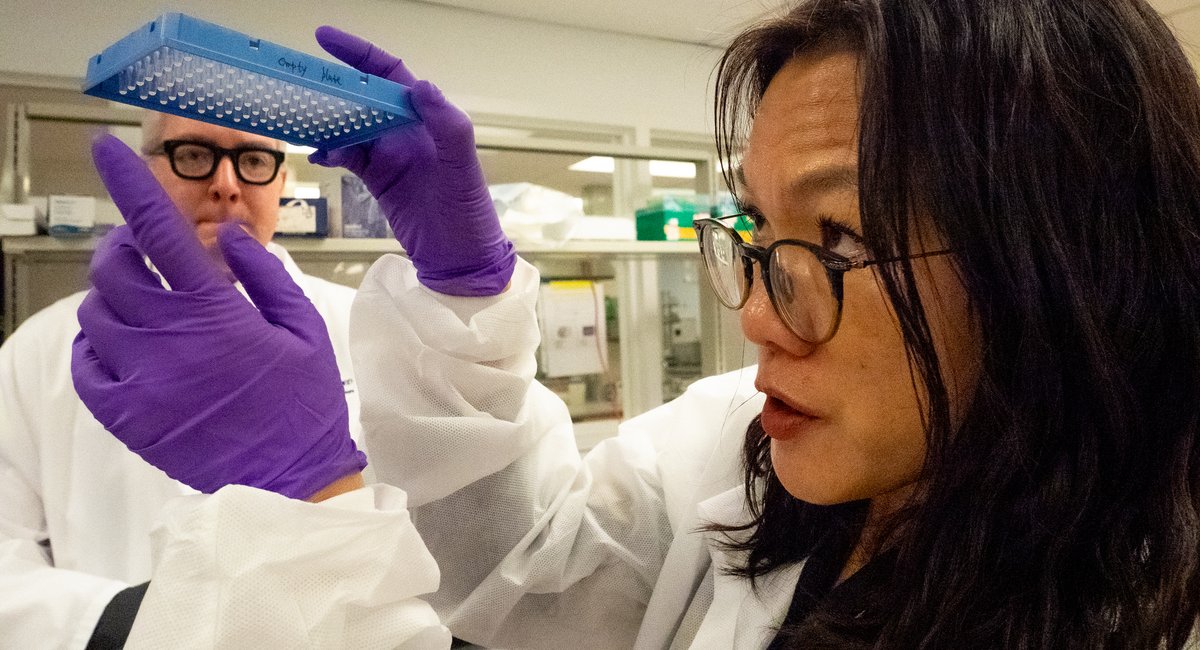

The medical examiner’s office investigates approximately 40,000 deaths per year in New York City. Its molecular genetics laboratory, founded by Dr. Yingying Tang in 2003, is the only one of its kind in a medical examiner’s office in the country — most other jurisdictions send samples to private labs.

That in-house capability allows the lab to perform about 500 molecular autopsies each year, identifying genetic causes of death in roughly 100 cases. Those conditions include epilepsy, Long QT syndrome and other cardiac arrhythmias — heart rhythm disorders that can cause sudden death but are often treatable with medication or lifestyle changes.

Other medical examiner’s offices that rely on private labs face a fee-for-service model that limits testing. Rather than screening hundreds of genes, they may only test for conditions they already suspect — potentially missing true causes of death, city officials said.

Until now, at-risk family members in New York were referred to outside clinics for their own genetic testing. But some never followed through.

“Sometimes these are people of meager means who just lost a family member and we’re able to help,” said Sarah Saxton, a genetic counselor at the medical examiner’s office. “Sometimes they don’t have time to make a doctor’s appointment.”

Under the new program, families can come to the medical examiner’s office for a simple oral swab, or receive a test kit by mail. Graham said the city budgeted $600,000 to fund four lab scientists, an additional genetic counselor and equipment.

Tang said her team uses next-generation sequencing to cast a wide net.

“The human genome is 20,000 genes long — we only have to analyze for 300 different genes to see if they have the markers for this range of diseases,” she said.

Dr. Michelle Jordan, vice president of the National Association of Medical Examiners and a practicing medical examiner in San Jose, California, said the program could serve as a model for other jurisdictions.

“If they’re offering in-house testing, that would really streamline the approach — not just for the autopsy itself, but for the families,” Jordan said. “If they find a gene like Long QT syndrome and those next of kin don’t have a doctor, that would be an added advantage.”

Graham said he made the $600,000 program a budget priority because of the life-saving potential.

“We’re in a very unique position to access a population that is often being untouched by any other sector of the government,” he said. “It has the potential to be very direct, lifesaving work.”