Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

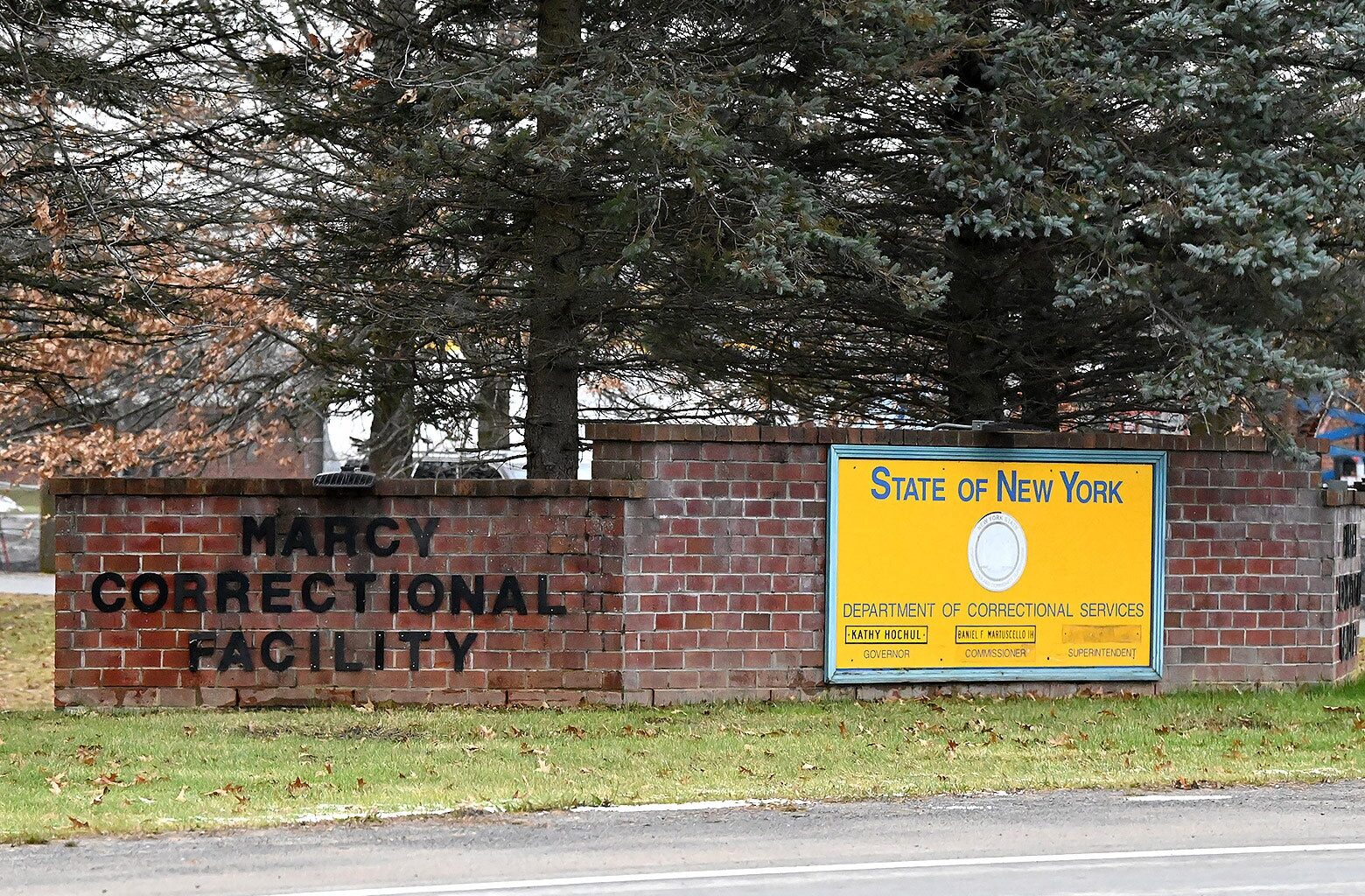

On Nov. 17, Abdallah Hadian, a civilian imam, strode into a state correctional facility in New York with a firearm. Moments later, he went into the administration building and placed the gun to his head.

Word of the 55-year-old imam’s suicide traveled nearly as quickly as the bullet that took his life.

In prison, no one bats an eye at hearing that an inmate killed themselves. This is especially true among fellow prisoners. Hearing that a fellow prisoner was stabbed to death, or overdosed, elicits a shrug, maybe a nervous laugh. Although we attribute such incidents to the violent and miserable nature of the place we inhabit, most people on the outside chalk these deaths up to the so-called mental health crisis inside correctional facilities, a phenomenon that gets significant attention. It adds to the unfair narrative of prisoners being bloodthirsty lunatics, a framing that benefits tough-on-crime politics.

As a prisoner, though, when you hear that a civilian staff member who left their family every day to go to the awful confines of prison—the same prison where Robert Brooks was murdered—took their own life in such a shocking fashion, it makes you wonder what we’re doing wrong. More importantly, the question swings in the air: What might someone who is living in the free world but considering killing themselves learn from prisoners about hanging on?

I’ve been there. I’m serving my 16th year for manslaughter. In 2009 a drunken argument with my girlfriend devolved into a physical altercation with deadly weapons. She stabbed me, I stabbed her, she died. I immediately attempted to end it all.

Obviously, I didn’t succeed. In the hospital, I soldiered through the physical misery of a collapsed lung. Then I wrestled with the shame and guilt of killing someone that I had loved, emotions that were all the more amplified when I was forced to relive the trauma in court. I’d be lying if I told you that I hadn’t contemplated every means of suicide.

I believe that I Iived through that awful and tragic experience to be held accountable, not only by the victim’s family but, less sympathetically, to the mirror. The pressures of life, which in that moment felt unbearable, proved bearable.

In my role as a journalist, I found purpose and draw from that dark place when reporting stories about characters who have their own dark encounters. I think it has enabled me to develop as a writer who draws out the humanity of prisoners that the tabloids leave behind. In interviewing the subjects of my stories, I always find myself threading our shared experiences into narratives pegged to universal themes like parenting, drug use, and—for obvious reasons a reoccurring motif—the feeling of the walls closing in. But the experience of isolation in prison is not monolithic.

Like most of the prisons I’ve had the displeasure of living in, Eastern NY Correctional Facility during the “happiest time of the year” offers no gifts under a Christmas tree. No “Happy Holidays” decorations. Just yellowed suicide-prevention memorandums posted on the bulletin board. Guys live here under the weight of life sentences and have been away from their families and loved ones for decades. Other guys haven’t gotten visits in years but still find reasons to wake up, to put both feet on the ground, and, oddly enough, even to smile.

I can’t help but admire the resiliency of old-timers, some of whom have lost every family member, who have more time in prison than I have on this earth. They keep it simple, play Scrabble or spades and talk shit. Once able-bodied men, they walk with canes, one step at a time.

It is the coping mechanisms of the prisoner, our survival under this added layer of extreme inhumanity, that may make us the most apt case studies for suicide prevention.

One day this season, I overheard some of the GED students inside our school building tell the prison’s acting educational supervisor, Nicole Cooke, that they didn’t have anything to be grateful for during the holidays.

Bianca Garcia and Jason Bryan Silverstein

One of the Most Basic Rights in the Book Is Regularly Denied to ICE Detainees

Read More

“I didn’t like that,” she told me from behind a large wooden desk. This gave her an idea.

She had a tree painted on the wall, leaving the branches bare. Photocopied drawings of jars containing the words I’m thankful for were distributed to everyone who wanted to decorate the tree. She told guys to write what they were grateful for inside the paper jars, which stood in for the tree’s leaves.

Although the gratitude tree remained on the wall for about a month, as I attended my classes I walked right past it without reading a single jar.

The same day that I went inside the school building to finally put my own note on the gratitude tree, the jars had been taken down. I spoke with Cooke, and she removed them from her drawer and handed me the stack of paper jars. I sat down alone in the academic library and counted 82 altogether. I plucked through them one by one, reading their contents. Forty-six of them contained the word family or mi familia. Some included only a word or two, like mom or even Ms. Cooke. Suddenly, I realized that in my hands these small pieces of paper weighing next to nothing contained something so heavy and intimate—people and things that gave my community a sense of hope and purpose, reasons for living. I felt a little wrong riffling through them, but I was inspired to witness a collective will to live. As Albert Camus said, “Rarely is suicide committed through reflection.”

That’s when I noticed that a handful of these jars had been filled out by staff, people who, like Hadian, the imam, get to go home every day. Their end-of-year reflections had been displayed side by side with the prisoners’ jars on the tree: a shared message of thankfulness and hope displayed for everyone who took part or who bothered to look.

Sign up for Slate’s evening newsletter.