It has long been accepted fact that football’s richest league resides in England. The Premier League was not immediately a financial behemoth when it was formed in 1992 but today, 33 years and billions of pounds later, there is no doubting where the money lies.

That is borne out every few months when a new transfer window rolls around, and the English clubs splurge like no others. Wage bills, too, are dominated by Premier League sides. In 2023-24, the most recent season for which we have a full dataset, teams from England occupied nine of the top 20 spots in the list of European football’s highest payers.

The money swirling around the English game has naturally made it an attractive proposition to would-be buyers. As detailed by The Athletic before the current season began, the Premier League’s club owners are vast and varied. A collective 78 per cent of the 2025-26 season’s 20 competing sides is owned by non-UK individuals or enterprises, and the sources of wealth which have allowed those owners to buy into British football span a multitude of industries.

With all that money and all that interest, a natural question poses itself: how much are Premier League clubs worth?

The query is an intractable one. Just as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so some might find value where others scoff.

Since the beginning of the 2019-20 season, during which the Covid-19 pandemic badly affected finances across football, out of 102 pre-tax results published by Premier League clubs, only 27 (26 per cent) were profitable. Yes, Covid-19 played its part, but it is telling that even after the pandemic subsided, many teams continued to lose money, in large part because the growth in wages and transfer fees has outstripped revenues.

Roger Bell, who formerly co-founded consultancy firm Vysyble and still tracks industry numbers, highlights to The Athletic that in the 16 seasons from 2008-09 to 2023-24, Premier League clubs made an economic loss — a performance measure which takes into account all the costs, to the ownership, of doing business — of £7.87billion ($10.6bn at the current rate). Perhaps even more striking is that around half of that loss came from just six teams: Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur.

That those same six sides are routinely valued the highest would therefore seem bemusing. How can a club be valuable if it costs the ownership so much in capital to run them?

Of course, football is unlike many other businesses, and prestige remains a huge factor. What’s more, perhaps unspoken by many but increasingly true, lots see value in the idea that clubs will continue to accumulate value in the eyes of others: owners might not be able to draw cash out in dividends but, eventually, they’ll be able to sell up at a nice profit to willing buyers.

To that end, The Athletic has pored over industry estimates, looked at recent club financials and cobbled together estimates of our own.

Value is a movable feast, particularly for those teams that drop out of the league’s bottom end each May. What’s more, broader factors which would directly impact club values are unknowable; income from TV broadcast deals could fall, new rules could restrain investment or, whisper it, something like a European Super League could rear its head in an unknown future.

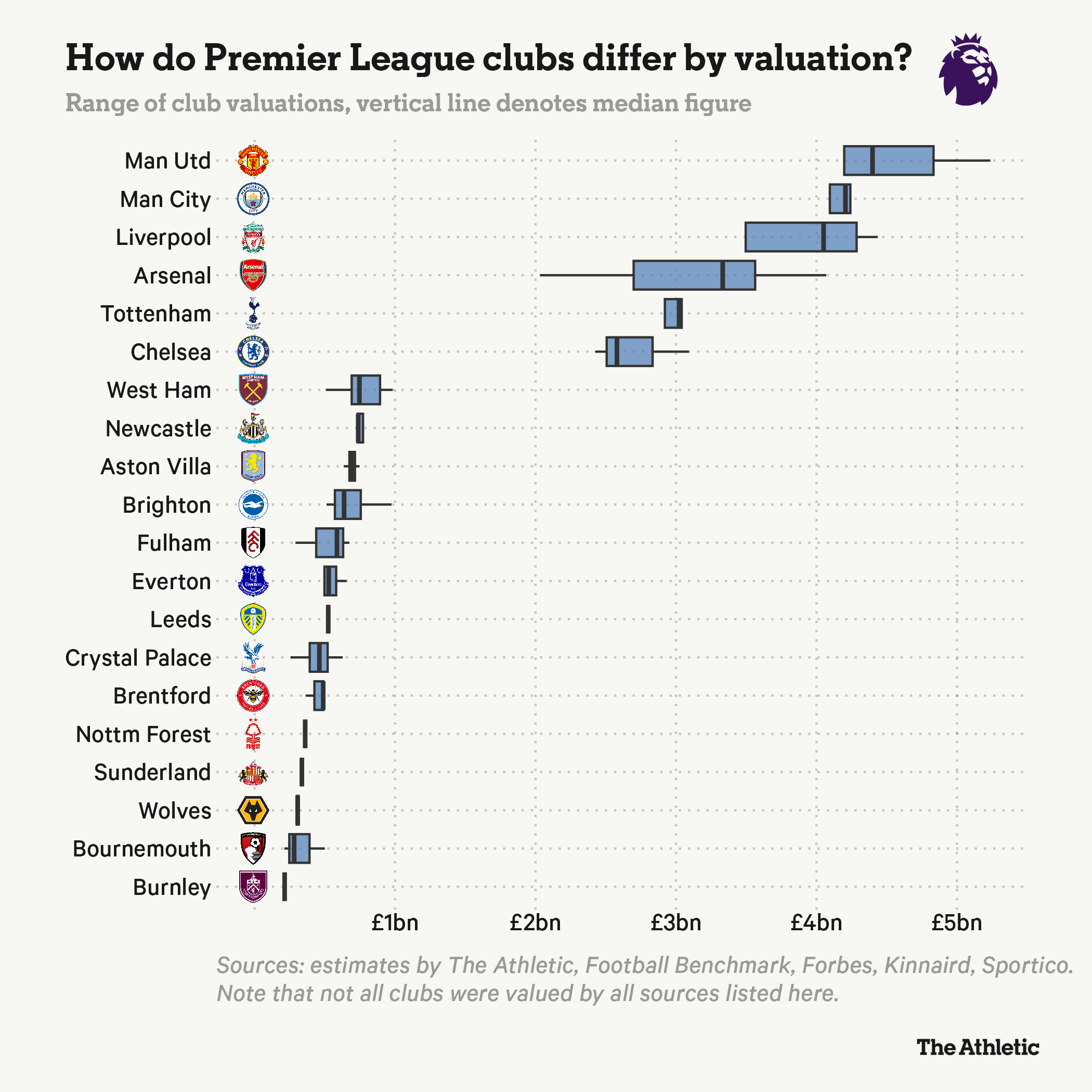

As a result, putting a definitive figure on each club is a fool’s errand. But we know, or can estimate, enough to bucket them up into broader categories. And our work and research have yielded a range for each team which, at the very least, is a decent indication of their individual worth.

These ranges have been put together courtesy of estimates by The Athletic, Football Benchmark, Forbes, Kinnaird and Sportico.

This first graphic, perhaps unsurprisingly, shows a clear hierarchy among English football’s top 20. How we reached these results is explained below.

The ‘Big Six’ (£2.5billion-plus)Manchester United (The Athletic’s estimate: £4.2bn-£4.6bn)

The ‘Big Six’ (£2.5billion-plus)Manchester United (The Athletic’s estimate: £4.2bn-£4.6bn)

As England’s only publicly listed club (excluding the 13 per cent of Tottenham Hotspur which can be traded every other month), Manchester United are the one Premier League side for whom we have a running, up-to-date valuation.

The stock price at the time of writing of around $16 (just under £12) translates to a market cap of £2.06billion. Add the debt on and deduct the club’s cash balance, and you get to an enterprise value of around £2.7bn — a figure well below where most observers peg United’s current value.

And also below where Sir Jim Ratcliffe put it when he bought up over a quarter of the club in February 2024. Then, Ratcliffe bought in at $33 (£26.16) a share, leading to a deal which valued United at £4.3billion.

United have long been English football’s monolith, even as footballing performance has crumbled since Sir Alex Ferguson’s 2013 retirement as their manager. In many of the publicly available lists of club valuations, United continue to top the Premier League.

Both Manchester City and Liverpool can be said to give them a good run for their money, but even amid a financial picture which led to up to 450 jobs at United being scythed, their stature is such that they probably still remain England’s most valuable club, with a worth not dissimilar from the amount Ratcliffe’s deal indicated.

Manchester City (£4bn-£4.4bn)

In 2008, Manchester City were snapped up by the Abu Dhabi United Group (ADUG) for around £200million, a figure which bears little resemblance to the club’s worth now. The latter has been borne out in the huge changes at City over the past 17 years, as well as share sales in the intervening years.

Six years ago, American private equity firm Silver Lake snaffled up 10.4 per cent of the club’s parent entity, City Football Group (CFG), for $500million (£388m at the time). The deal valued CFG at $4.8bn (£3.7bn).

Of course, CFG is not City alone, even if they were the first and remain the foremost jewel in a sizeable multi-club crown. That £3.7billion valuation might have primarily comprised City, but it also covered all of CFG’s numerous accoutrements, and it is difficult to see how City the club and City the group could now exist without one another. As The Athletic has previously detailed, the club wage bill disclosed in reports by European football governing body UEFA for City is a fair sight higher — 15 per cent in 2023-24 — than that detailed in the Premier League side’s standalone accounts, reflecting the size of the contribution CFG makes to operations at the stable’s premier side.

Valuing just the team who play their home games at the Etihad Stadium is tricky, then, though in truth, if City were to ever be sold in full, it would almost certainly come as part of a broader CFG package. Wherever that figure landed, it is clear that, albeit through huge investment and a favourable regulatory landscape in the early years of ADUG, City are now one of the Premier League’s most prestigious clubs and, like United, top the £4billion mark.

Liverpool (£3.9bn-£4.3bn)

When Fenway Sports Group (FSG) bought Liverpool for £230.4million in October 2010, it took over a club brought low by a leveraged buyout, which immediately wreaked havoc on finances.

Fifteen years on, Liverpool were in a position where they could spend some £400million on new players in the most recent transfer window, a feat only one other English club had previously managed. Under FSG, they have won two Premier League titles and a Champions League, and are in the midst of huge commercial growth off the field.

Improvements to club facilities, both at their home stadium Anfield and in the building of a new training ground, have combined with FSG’s canny financial management and Liverpool’s longstanding renown and global supporter base to create a hugely valuable football club. Regular valuers of Premier League clubs tend to have them either second only behind Manchester United, or third, with the other Manchester outfit now separating the two teams in red.

FSG encompasses other sports, meaning its value isn’t quite so analogous to Liverpool’s as CFG’s might be to City’s. But a transaction in September 2023 was instructive. Then, Dynasty Equity bought a stake believed to be around three per cent. Using the £127.3million which subsequently flowed to club coffers got us to an FSG football, and therefore Liverpool, valuation of £4.24bn — more than 18 times what the group paid in 2010.

John W. Henry’s FSG own the majority of Liverpool (Michael Regan/Getty Images/Getty Images For The Premier League)

Arsenal (£3.2bn-£3.5bn)

Already 67.05 per cent shareholder KSE Inc UK, ultimately owned by Stan Kroenke, acquired a further 30.05 per cent stake in Arsenal from Alisher Usmanov in 2018 for £550million, valuing the club as a whole — which KSE now entirely owns — at £1.83bn.

Arsenal’s value has risen since then, via a combination of a broader uptick for English clubs and KSE’s own significant backing. The owners have helped turn the north London side back into bona fide title contenders and, this season, a team prominent in discussions about potential Champions League winners, too.

Some observers are more bullish on Arsenal than others, with the odd £3billion valuation sneaking in. Others feel they sit below that, but above the £2bn mark. The complicating factor in all of this is that revenues are growing rapidly at the Emirates Stadium; turnover was up 24 per cent and £150m in 2023-24 alone, with a further £50m-plus increase likely once 2024-25 financials are released.

Factor such growth in and apply a revenue multiple in keeping with that of the biggest clubs, as The Athletic has done, and Arsenal’s valuation would top £4billion. In part as a result of the quick increase in turnover, their range across our sample of independent valuations is the widest among the 20 clubs.

Tottenham Hotspur (£2.9bn-£3.2bn)

Sales talk was rife at Tottenham Hotspur after they sought potential external investment via Rothschild & Co, although that has now ended after majority shareholder ENIC said it had no desire to sell. But speculation about the club’s value has long been part of the background music in their part of north London.

The Athletic has previously detailed their chairman Daniel Levy’s desire to obtain a selling valuation of £3.75billion for Spurs. He is, of course, no longer involved at the club. Onlookers have often thought that valuation too high, with a mark closer to £3bn generally deemed more appropriate. The Lewis family, who own Spurs through ENIC, have bucked years of trend, investing notable recent sums at a club which long ran on their own resources while Levy was chairman.

Having already built themselves a stadium that is the envy of most clubs, not just at home but worldwide, spending this new money wisely and building a team which can compete regularly might help push Tottenham’s value up to that level.

Chelsea (£2.5bn-£2.7bn)

Roman Abramovich’s decision to put Chelsea up for sale following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine led to the last time a ‘Big Six’ club were sold in full. Three months after all-out war began, Chelsea were snapped up by a consortium led by Clearlake Capital’s Behdad Eghbali and Jose E Feliciano.

The group paid £2.5billion for the club, albeit with £150m in deferred consideration that, per the accounts of Abramovich’s selling company, is deemed unlikely to have to be paid. Chelsea’s new owners also committed to investing a further £1.75bn in the club over the next 10 years, a promise they’ve made much headway on: nearly £800m in owner funding went into the club in their first two seasons in charge.

Chelsea’s value is both pushed and pulled by their location. On the one hand, they’re in affluent west London; on the other, difficulties in securing either improvements to their Stamford Bridge stadium or building a new home ground limit the club’s growth potential. Other than Manchester City, who are in the midst of extending and improving the Etihad, Chelsea are the only club among the ‘Big Six’ who don’t earn over £100million a season in matchday income.

Club valuers generally don’t seem to think the needle has moved on Chelsea much since that 2022 takeover, even as the club have spent heavily. Figuring out the Stamford Bridge situation might help.

The contenders (£500million-plus)West Ham United (£710m-£780m)

West Ham’s ownership group welcomed its newest member in November 2021, when Czech investment group 1890s Holdings, helmed by energy magnate Daniel Kretinsky, purchased a 26.99 per cent stake in the east London club for £182.5million.

That valued West Ham at £676million, which seemed about right and in keeping with their football standing: some way off the ‘Big Six’, but very much aiming to be one of the best of the rest. On-pitch performances have waned more recently, and the current season is as obvious a relegation battle as you could expect to see. Going down would, naturally, depress West Ham’s value.

West Ham are a curious club financially, laden with contradictions that their London Stadium home bears out best: they don’t own it, which generally isn’t useful for a valuation, but the lease they hold is incredibly generous and won’t expire until 2115. At which point, most investors today would surmise, it will be someone else’s problem.

Their location in the UK’s capital stands them in good stead, even if attendances would be expected to drop in the second-tier Championship.

West Ham’s valuation, a high one by the standards of most English clubs, is the one among our list which is the likeliest to tumble the most if they were to be relegated this season.

Newcastle United (£700m-£770m)

Newcastle’s transformative takeover was a little more than four years ago but, even then, the £305million paid by a consortium led by Saudi Arabia’s state Public Investment Fund (PIF) to end the reign of Mike Ashley seemed a bit of a steal.

In their years under Ashley, Newcastle were underfunded and treading water and, as PIF and partners identified long before the takeover actually went through, ripe for growth. Fans flocked in post-sale, commercial revenues are ticking up and, though profitability and sustainability rules (PSR) have prevented PIF pouring in the amounts of money Manchester City received from their Gulf state-linked buyout 13 years prior, Newcastle have still received more owner funding than most. A £45million share issue this month took total new cash into the club to nearly £500m in four years.

Newcastle’s value has risen with their on-field stock, where they have gone from mid-table and occasional relegation-fearers to a club who have played Champions League football in two of the past three seasons. Winning the Carabao Cup last season might not add loads onto a club’s value, but it didn’t hurt the feeling of Newcastle as a team on the grow, nor does the ability to tap into the enthusiasm that the takeover set in motion. Matchday takings at St James’ Park are up considerably.

Speaking of, their home stadium is probably the next main impediment to further value growth as, several years into the role, the club’s current owners are yet to decide what to do: revamp Newcastle’s iconic current home or build a new one. Works have taken place to improve what was a rudimentary training ground.

Newcastle’s value has grown since 2021 and, in many eyes, at least doubled. Infrastructure improvements will be needed to maximise it.

Infrastructure improvements are needed at Newcastle (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

Aston Villa (£660m-£730m)

It is more easily forgotten now, but when Aston Villa were bought by Nassef Sawiris and Wes Edens from Tony Xia in 2018, they were a Championship side and in a financial crisis under Xia, as reported the following year by The Athletic.

Under the duo, Villa have received huge amounts of owner funding, and results have flowed accordingly: mid-table in the second-tier Championship less than a decade ago, they contested a Champions League quarter-final this year.

Villa’s growth has been primarily owner-backed, so in recent seasons, they’ve rubbed up against rules-based trouble. In turn, that has seen plans to revamp Villa Park given greater impetus and importance, which in turn would add to a valuation that has increased hugely since Sawiris and Edens took over. Atairos Partners, an American investment company, has bought up a 31.08 per cent holding in V Sports, Sawiris and Edens’ management company which owns 100 per cent of Villa as well as smaller stakes in a club apiece in Portugal and Spain.

Atairos invested nearly £100million into V Sports in 2024, raising its stake in the group by 9.79 per cent as a result. Extrapolate that, and you get to an overall V Sports valuation of £1.021bn, much of it attributable to Villa.

Again, the club have received enormous owner funding since 2018 but that value eclipses it — most think it bullish and that Villa should still be some way shy of £1billion, but the club’s worth will only rise if they continue to compete for Champions League spots and get those stadium works done.

Brighton & Hove Albion (£610m-£670m)

Brighton are a club far removed from the day Tony Bloom assumed a controlling interest at the end of the 2000s, spending less than £20million to bump his shareholding in the then third-division club up to the 77 per cent mark.

Bloom’s inputs have been significantly higher since, but then so, as a result, is Brighton’s valuation.

Widely held up as one of the smartest clubs in English football, Brighton have become Premier League mainstays, boast a modern and well-appointed stadium with a capacity nearing 32,000 and, in both 2022-23 and 2023-24, profited so much from their player trading model that they were able to repay Bloom over £100million of shareholder loans which had at one point topped £400m, as seen in their accounts across 2022-23 and 2023-24.

Those debts were still a smidgen under £300million at last check, but all of the valuations included in our sample suggested Bloom would be able to earn that money back and more besides.

Brighton’s is a tale of huge value enhancement over less than two decades; the curious unknown is whether hypothetical new owners would be able to keep up the outstanding work of the Bloom era or whether the club’s value rests more heavily on his shoulders.

Fulham (£560m-£620m)

Fulham’s frequent toing and froing between the top two divisions has abated in recent seasons, and the completion of the new Riverside Stand at their Craven Cottage stadium has helped raise the value of a club acquired by current owner Shahid Khan for £121.1million in July 2013.

Khan’s investment in the west London club since that date has far outstripped the purchase price. In November 2024, it was estimated that this topped £766million. To that end, making his money back were he to sell looks difficult, albeit far from impossible.

Fulham benefit from location, and much will be dictated by the cash that flows from that new stand. If they can spin big money from it, it will help elevate a valuation towards the near £900million Khan has invested so far.

Everton (£500m-£550m)

Years of ownership woes and worries came to an apparent end for Everton in December last year, when Roundhouse Capital Holdings (RCH), a UK-based holding company for The Friedkin Group, Inc. (TFG), bought Farhad Moshiri’s 94.1 per cent stake in the club. Subsequent activities have seen RCH’s holding rise to 99.5 per cent.

Everton’s valuation is made even more complicated by the Hill Dickinson Stadium: the cash flowing from their impressive new home, which opened this summer, isn’t yet publicly known. Even so, Everton look in a much less parlous state than they did as recently as just over 12 months ago. Troublesome loans have been refinanced and TFG has already shown a willingness to fund its new acquisition.

Combine those factors with a stadium which should increase club revenues markedly on what could be earned at predecessor Goodison Park and we’ll be able to more confidently predict Everton as a club pushing beyond that half-billion-pound valuation mark.

Leeds United (£500m-£550m)

After two years away, Leeds are back in the Premier League this season and under new management with 49ers Enterprises. As detailed by The Athletic in September, the owners put the club’s valuation following promotion in May at £527million, aided by significant recent shareholder investment.

That, of course, was a valuation sent forth by an ownership group in a pitch deck looking to attract further investment; it is hardly devoid of motive.

Even so, Leeds’ value has jumped with their top-flight return and, even before it, they were one of the more valuable non-Premier League sides, boasting strong support which translates into impressive matchday and commercial revenues.

Both that pitch deck and the club more widely have detailed impending works to their Elland Road stadium, with expansions intended to increase capacity by around 9,000 to 47,000 for the 2028-29 season. A further increase to 53,000 is in the planning.

Leeds are targeting a £1billion valuation by 2030, and while there’s still some way to go on that, it isn’t as outlandish as it might be for other recently-promoted clubs. Those Elland Road works will boost income, and projections in the deck detailed revenues of £271m by 2027-28.

A standard revenue multiple for a club such as Leeds would leave them still some way shy of their aim, but an upward trajectory for a club with their backing, both in the stands and, now, the boardroom, makes that aim achievable.

The restCrystal Palace (£440m-£480m)

Other than the publicly-listed Manchester United, Crystal Palace offer us the most recent reliable example of how much any of the Premier League’s clubs are worth in today’s market.

At the end of July, 42.92 per cent of Palace changed hands, as John Textor’s Eagle Football Holdings (EFH) sold that stake, the largest holding of the south London side’s varied shareholder base, to Woody Johnson, owner of the NFL’s New York Jets. Subsequent public filings from EFH disclosed that Johnson paid $205million (£151m using the exchange rate on the day of the transaction) for a little over two-fifths of Palace.

In turn, that valued the club as a whole at £353million — which was around £100m below the average of figures in our sample and calculations.

A couple of things depressed the value of EFH’s stake when selling to Johnson.

For one, Textor was keen to get out. He and executive chairman Steve Parish were not aligned in their views over how Palace were run or multi-club ownership. And they won last season’s FA Cup, creating issues around European qualification.

The second factor limiting value relates to how control of Palace is divided up. In general meetings, the club’s main shareholders have equal say, regardless of the size of their stake. Voting rights more closely track share percentages in other matters. A full sale of Palace should value them higher than last summer’s figure of £353million.

Woody Johnson bought a significant shareholding in Crystal Palace (Ed Mulholland/Getty Images)

Brentford (£340m-£380m)

Much like Bloom at Brighton, Matthew Benham took over at Brentford when his boyhood club were in England’s third tier.

Benham started by loaning the west London side monies, which could be converted to shares, but by the time he assumed a 96.23 per cent holding in June 2012, the cost of purchasing Brentford was pretty low; cobbling together public records suggests less than £10million got that job done and that under £20m took him to 100 per cent ownership.

Though Benham has put in more money since, it has long been usurped by the club’s value. Brentford are now in their fifth consecutive Premier League season, have a player-trading model the envy of many and, crucially, have replaced the quaint but decaying Griffin Park with the small (capacity: 17,250) but well-appointed and modern Gtech Community Stadium.

Expanding the Gtech isn’t an option due to its location, and there’s a limit to how high Brentford’s value as a club will go. That is perhaps borne out in Benham’s recent decision to cash in on the undeniably impressive work done under his hand; he sold a 10 per cent stake to Gary Lubner and Matthew Vaughn in June this year, and those two have the option to buy a further 15 per cent before February next year.

Monetary specifics weren’t disclosed, and while The Athletic reported Benham was keen to secure a valuation of £400million for Brentford, public filings for Best Intentions Analytics, the holding company which owns the club and in which Lubner and Vaughn bought their stake, suggest an overall valuation closer to £350m was achieved. That figure is not certain but would track to The Athletic’s estimate, even as some others put the club’s value at around £100m higher.

Nottingham Forest (£340m-£380m)

Evangelos Marinakis and business partner Sokratis Kominakis took full control of Nottingham Forest in May 2017, 80 per cent in Marinakis’ favour. Since then, they have gone from fourth bottom of the Championship to playing in Europe.

Forest are among many clubs in the current Premier League boasting plans to improve their stadium, with a public consultation period announced in early December over plans to expand the City Ground to a capacity of 52,000.

Doing that would naturally enhance Forest’s value and would also underline the level of support they can call upon. Marinakis has invested a lot since taking over, but continued Premier League status has helped move their value towards a favourable position even against the money sunk in to date.

Sunderland (£320m-£350m)

Sunderland are the most difficult club to value of the Premier League’s current cohort, by virtue of this being their first season back in the top flight in eight years. That fact renders using recently published financials worthless when generating a valuation of the club today, and also means there’s a dearth of publicly available valuations.

What is obvious is that Sunderland’s value has risen significantly since current chairman Kyril Louis-Dreyfus first took up a stake in the club in February 2021. Louis-Dreyfus didn’t manage a majority share until later than that but, even with a distinct lack of clarity around how much he ultimately paid for a holding which now sits at 64 per cent, it is clear he and co-owner Juan Sartori are sitting on an asset worth much more than they’ve so far invested.

Value has been driven by savvy player trading, as well as tapping two resources which were already present but poorly utilised by past owners: infrastructure and the fans.

On the former, the current regime has undertaken a refresh of the Stadium of Light, which, when isolated, would look minimal but in combination improves a home ground that was starting to look tired, having opened in the late 1990s. Noteworthy sums have also been spent modernising the training ground. An already ardent fanbase have been wooed by impressive marketing and commercial offerings, while zooming up the pyramid from the third division has hardly hurt; home games are now routinely sold out, even as ticket prices have risen.

A Bloomberg report recently suggested a party had, unsuccessfully, tried to buy a stake at a price which would have valued Sunderland at an overall £450million. Even if that were rejected, it seems high for a team only six months into their top-tier return after almost a decade in the lower divisions, but this club’s worth is only heading one way.

Wolverhampton Wanderers (£280m-£310m)

Valuing Wolves becomes rather trickier when we consider their current situation: rooted to the bottom of the table with just two points from the season’s first 17 matches.

Avoiding relegation from here might well drift into miracle territory, and it’s a fact of English footballing life that tumbling into the Championship can take a sledgehammer to a club’s value. Not all relegated sides are the same, and many bounce straight back, but from the current vantage point, it is impossible to confidently say Wolves would do that.

Being a second-tier side need not mean a low valuation, with both Ipswich Town and Wrexham recent examples of a zeal to buy into that division at a buoyant price, but those clubs’ trajectories were rather moving in the opposite direction to that of a relegated team.

Wolves were subject to a recent bid from none other than John Textor, who offered current owners Fosun $200million cash and $350m (£259m at the current rate) worth of shares in his multi-club Eagle Football Group, which Crystal Palace recently left. Over £400m for a team experiencing Wolves’ current malaise seems a pretty good deal, one which outstrips most valuations of them now, but, as The Athletic reported when the offer arose, there were plenty of complicating factors surrounding Textor’s bid.

Bournemouth (£270m-£300m)

Bill Foley’s Black Knight group took control of Bournemouth in December 2022, paying former owner Maxim Demin £120million for his full 100 per cent stake in the club.

Bournemouth were a Premier League club then too, albeit only just; that deal was inked four months into a first season back in the top flight after two years away. Three years on, Bournemouth might not be totally free from the fear of relegation, but they’ve certainly advanced as a club.

Even so, there’s a ceiling to their valuation in the current guise. That’s a byproduct of the spectre of dropping out of the Premier League — something most teams in the division are only one bad season away from — but also the club’s current infrastructure, or relative lack thereof. Their Vitality Stadium home holds just 11,307 spectators, comfortably the league’s lowest capacity.

Black Knight has overseen some impressive player trading in its short time in charge, and there has been longer-term work done, too. A new training ground finally opened in March this year, having first been announced in 2017; the pandemic waylaid plans under Demin but they got kickstarted under Foley. More broadly, he and Black Knight operate a multi-club structure, with Bournemouth its clear centrepiece.

Plans to nearly double their stadium’s capacity to 20,200 were unveiled this summer, with the works hoped to be finished ahead of the 2027-28 season. Getting that done and building out the club’s hospitality offering — another stated Black Knight aim — will help further enhance the value of a club who, while low relative to their peers, are steadily growing.

Burnley (£200m-£220m)

Burnley were taken over by ALK Capital in December 2020 in a £150million deal that sought to enhance the commerciality of a club who repeatedly had to punch above their own weight. Two relegations and two promotions since, and another relegation battle this season, make it difficult to argue Burnley’s value has been especially enhanced under their new owners, at least not yet.

By most measures, Burnley’s valuation as a current Premier League club probably sits around the £200million mark. Their Turf Moor home stadium is charming but old, even as a programme to install over 1,100 square metres of digital advertising displays has been completed under ALK.

Until they can both steer themselves northward of top-flight relegation battles with confidence and bring about more substantial infrastructure improvements, it is hard to see Burnley’s value rising much further.