By analyzing rare meteorites known as carbonaceous chondrites, researchers have shed new light on the elemental makeup of asteroids that formed over 4.5 billion years ago. These ancient rocks, fragments of primitive asteroids, may contain critical materials needed to build infrastructure in space and reduce reliance on Earth-based resources.

The push to understand asteroid composition isn’t just scientific, it’s strategic. As missions to the Moon and Mars become more realistic, sourcing materials directly from space could reduce mission costs and environmental impact.

One team, led by Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez at the Institute of Space Sciences (ICE-CSIC), believes that carbon-rich asteroids could one day serve as material reservoirs, particularly for extracting water and transition metals. According to their findings published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, meteorite analysis is helping to identify the most resource-rich asteroids for future missions.

Rare Meteorites Reveal the Hidden Chemistry of Early Asteroids

Carbonaceous chondrites, a type of meteorite that naturally falls to Earth, offer scientists a rare look at the makeup of undifferentiated asteroids, those that never melted or stratified. These primitive bodies preserve the original material from the early solar system, making them valuable for both research and potential mining.

According to Trigo-Rodríguez, “The scientific interest in each of these meteorites is that they sample small, undifferentiated asteroids, and provide valuable information on the chemical composition and evolutionary history of the bodies from which they originate.” Yet, they are rare: only about 5% of meteorites found on Earth belong to this category, and many disintegrate before they can be recovered. Those that do survive are usually discovered in desert regions like the Sahara or Antarctica, where dry, stable conditions help preserve them.

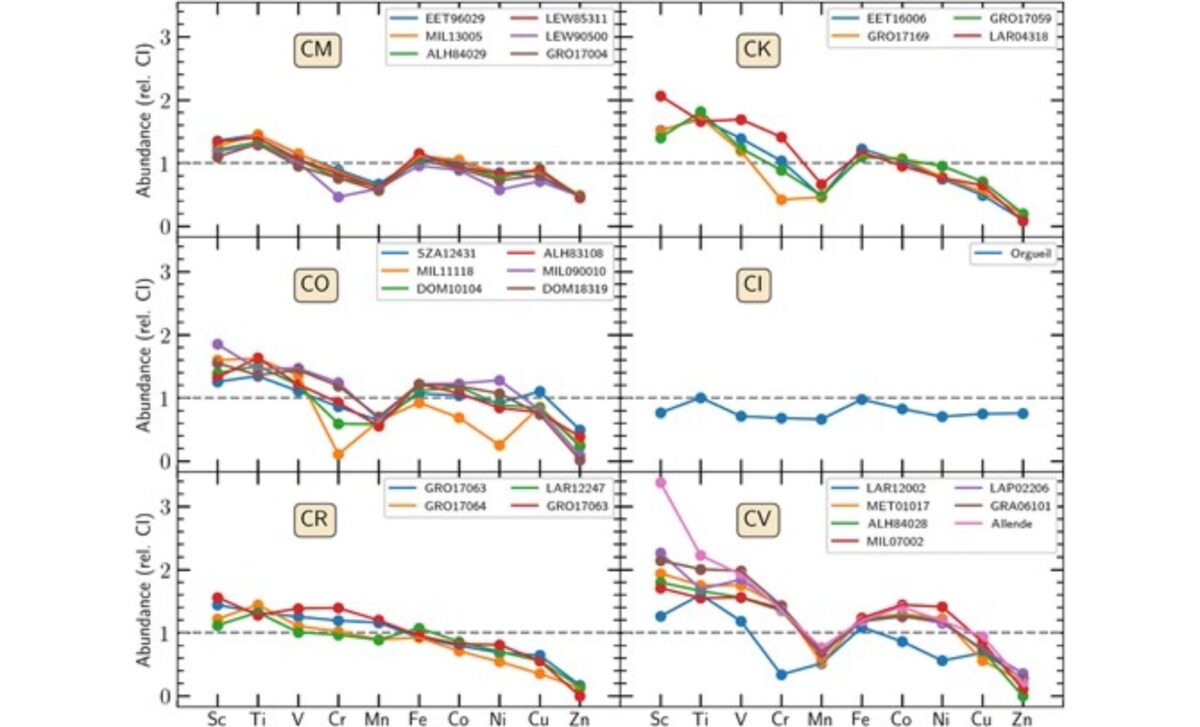

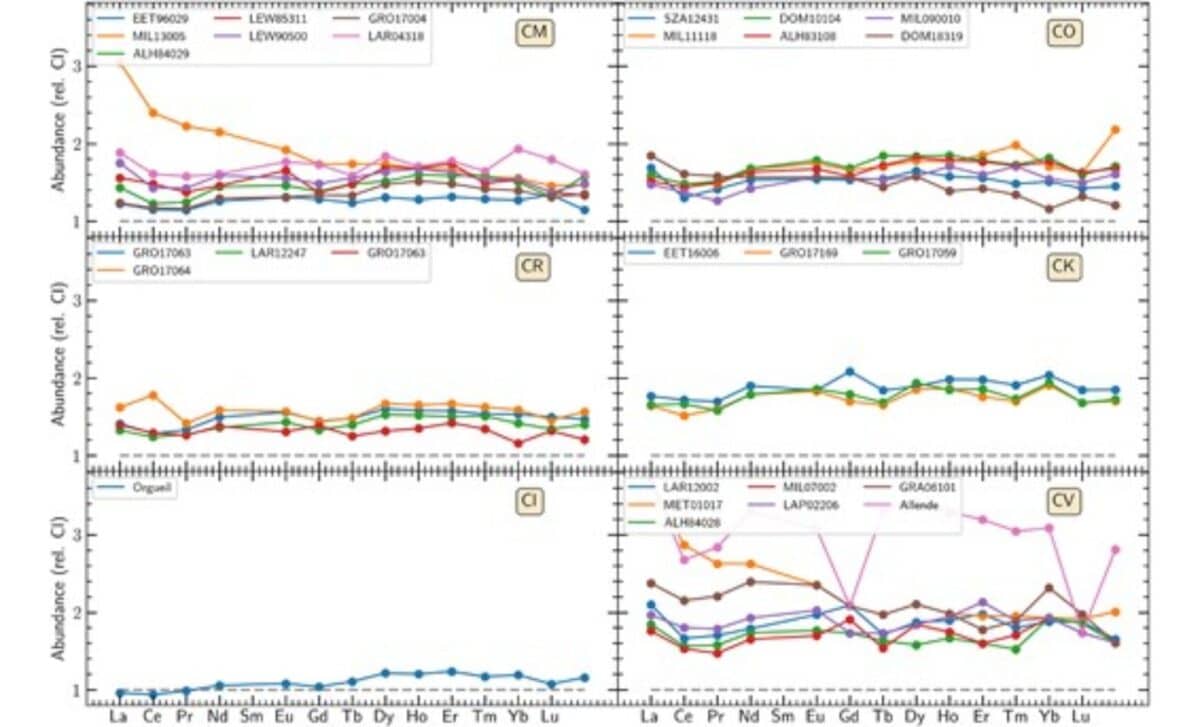

For the study, researchers selected samples across six chondrite groups (CI, CM, CO, CK, CV, and CR), many of which were retrieved from NASA’s Antarctic meteorite collection. Chemical analyses using ICP-MS and ICP-AES techniques revealed detailed information about the presence of transition metals like titanium and manganese, as well as trace amounts of valuable elements such as cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements. These insights are critical for evaluating which asteroids could be viable targets for future resource extraction missions.

Primitive Asteroids May Hold Metals, but Not All Are Equal

The ICE-CSIC team’s results point to significant differences in metal content between various meteorite groups. While many asteroids contain metals like Fe, Ni, and Co, the abundance and form in which they are found vary based on the asteroid’s history.

Data show that meteorites from the CV and CK groups are among the most titanium-rich, up to twice the concentration found in the CI group, considered the solar system standard. In contrast, other elements such as copper and zinc were often found in lower concentrations. CR chondrites, however, stood out with elevated levels of manganese.

These elemental variations are not trivial. As reported in the study, “Compared to the abundances on Earth’s upper crust… CCs have higher abundances of most transition elements,” especially heavier ones that aren’t as abundant in surface rocks due to Earth’s geological differentiation.

Still, the study makes clear that mining primitive asteroids won’t rival Earth’s richest deposits any time soon. While these space rocks do contain valuable elements, the concentrations are typically lower than those found in terrestrial mineral deposits. For instance, the abundance of REEs in most carbonaceous chondrites is 10 to 100 times lower than what is found in the Earth’s upper crust. Nevertheless, these asteroids may still prove valuable for missions in space, where launching materials from Earth is costly and logistically complex.

Asteroid Mining: Promising, but Far from Simple

The research team emphasizes that asteroid resource extraction remains highly experimental. According to Pau Grèbol Tomás, one of the co-authors, “Studying and selecting these types of meteorites in our clean room using other analytical techniques is fascinating… however, most asteroids have relatively small abundances of precious elements.”

The study notes that while asteroid regolith, the loose surface material, might make sample collection easier, scaling that up to industrial-level mining is an entirely different challenge. In fact, some chondrite groups have experienced aqueous alteration or thermal metamorphism, further complicating extraction due to altered chemical states of metals.

Asteroids of the K spectral class, which show olivine and spinel absorption bands, are identified in the study as promising targets, especially those linked to the CO and CV chondrite families. According to the researchers, these undifferentiated, relatively pristine bodies have retained their native metals without much alteration. That makes them strong candidates for future missions focused on mining operations or in-situ resource utilization (ISRU).

Jordi Ibáñez-Insa, a co-author from Geosciences Barcelona, adds that the environmental benefits shouldn’t be overlooked: “The search for resources in space could be susceptible to minimizing the impact of mining activities on terrestrial ecosystems.” Efforts like NASA’s OSIRIS-REx and JAXA’s Hayabusa2 missions are already returning material from asteroids like Bennu and Ryugu. These missions have begun validating the connections between specific asteroids and carbonaceous chondrite types, reinforcing the value of sample return missions in guiding future mining efforts.