In late September 2024, Hurricane Helene reached Florida’s Gulf Coast, bringing storm surges and widespread damage. At the same time, 88 kilometres above the surface, sensors aboard the International Space Station (ISS) registered a distinct pattern in Earth’s upper atmosphere. The detection has drawn attention to an emerging area of space weather research, revealing a direct link between major weather systems and dynamic atmospheric conditions far above ground level.

NASA’s Atmospheric Waves Experiment (AWE), installed on the ISS in November 2023, captured images of gravity waves—ripple-like disturbances in the mesosphere—that extended hundreds of kilometres from the hurricane’s impact zone. These wave patterns were recorded in the airglow, a faint emission of light produced by atmospheric gases.

This event provided clear visual evidence that a storm on Earth can influence the upper atmosphere in measurable ways. It also offered validation that the AWE instrument can reliably observe such interactions on a global scale. For engineers and atmospheric scientists, the discovery helps explain how weather near the surface affects conditions where satellites operate.

Gravity waves recorded over Florida

During Helene’s landfall on 26 September 2024, AWE detected concentric bands in the mesosphere, roughly 88 kilometres above the surface. These gravity waves formed circular patterns similar to ripples in water, expanding outward from the hurricane’s central region.

AWE principal investigator Ludger Scherliess, a physicist at Utah State University, confirmed the source of the waves. “Like rings of water spreading from a drop in a pond, circular waves from Helene are seen billowing westward from Florida’s northwest coast,” Scherliess said in a report from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Gravity waves in the atmosphere are triggered by disturbances such as hurricanes, thunderstorms, volcanic eruptions or mountain winds. They influence temperature, pressure and air density, particularly in the mesosphere, where they have not been widely measured on a continuous basis until now.

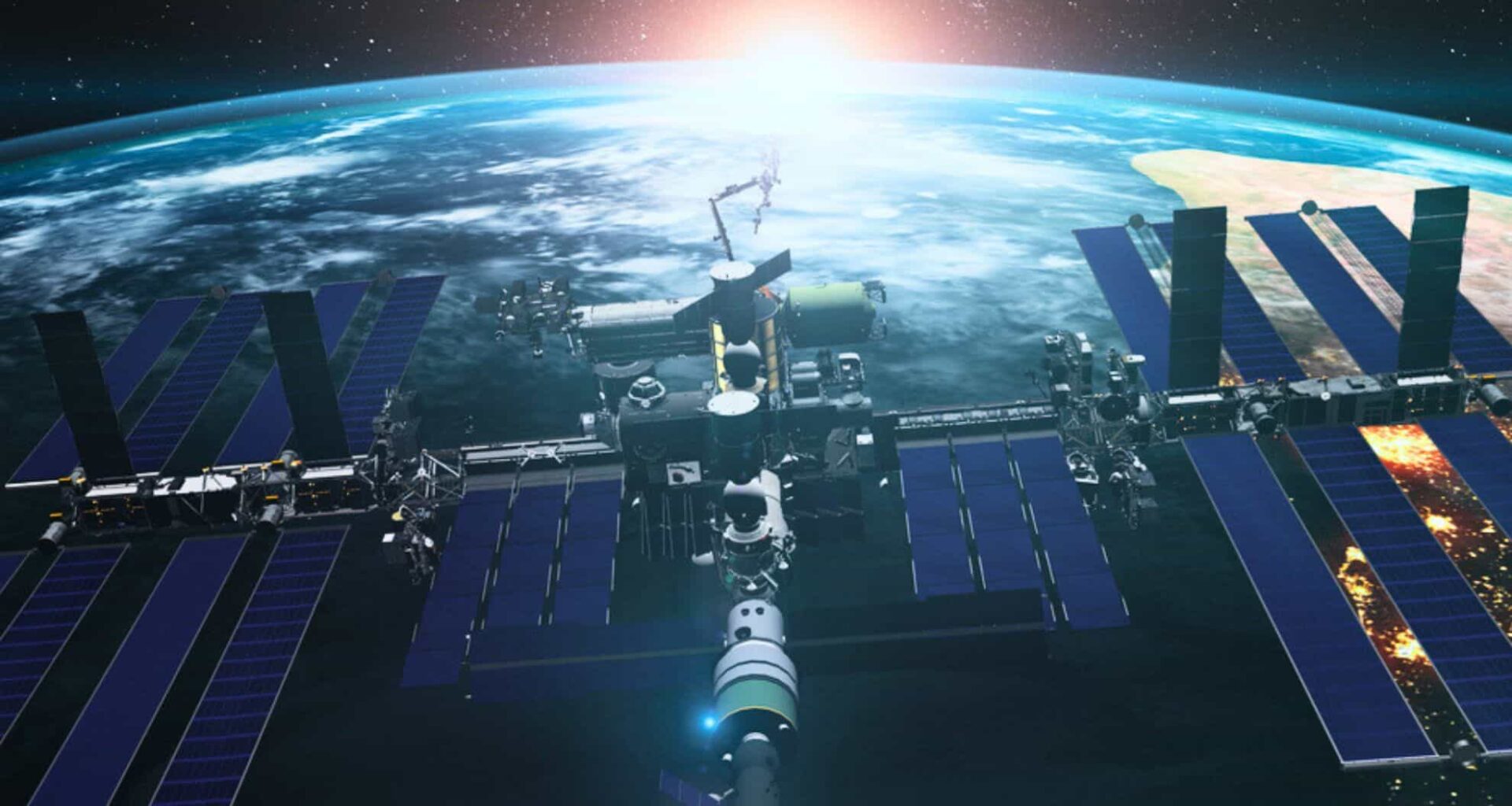

As the International Space Station traveled over the southeastern United States on Sept. 26, 2024, AWE observed atmospheric gravity waves generated by Hurricane Helene as the storm slammed into the gulf coast of Florida. The curved bands extending to the northwest of Florida, artificially colored red, yellow, and blue, show changes in brightness (or radiance) in a wavelength of infrared light produced by airglow in Earth’s mesosphere. The small black circles on the continent mark the locations of cities. Credit: Utah State University/NASA

By observing these waves through fluctuations in airglow, the AWE instrument enables researchers to identify how surface-level weather events can affect the structure of the upper atmosphere. NASA’s AWE mission overview describes this atmospheric layer as poorly understood due to its altitude, which is too high for weather balloons and too low for traditional satellite instruments.

AWE’s role in atmospheric research

The AWE instrument is part of NASA’s Heliophysics Explorers Program and operates in coordination with the Space Dynamics Laboratory at Utah State University. It is designed to examine how terrestrial weather contributes to space weather, particularly in regions of the atmosphere where previous data have been limited.

One of AWE’s key capabilities is its ability to track airglow, which becomes visible in specific wavelengths when high-altitude gases emit light due to solar energy. These emissions change subtly when gravity waves pass through the mesosphere, allowing for their detection and analysis.

Another tool in the mission, the Advanced Mesospheric Temperature Mapper (AMTM), plays a supporting role by measuring infrared variations linked to wave activity. The AMTM is sensitive enough to function in mesosphere temperatures, which can fall below -100°C, and adds further depth to the measurements gathered during storms such as Helene.

Mike Taylor, the former principal investigator of the AWE mission, described its launch in November 2023 as the culmination of decades of work in upper-atmospheric science. “From the ISS, our mapping camera will capture images from space on a global scale,” he said in an interview published by Utah State Today.

Implications for satellites and low Earth orbit

The mesosphere, despite being a low-density region, plays an important role in satellite safety and performance. Gravity waves can alter air density, which affects satellite drag. Even minor shifts in drag can influence the orbital path of spacecraft, leading to adjustments in positioning or lifespan reduction.

AWE’s detection of gravity waves linked to Helene provides actionable data for aerospace engineers and satellite operators. Knowing when and where upper-atmosphere disturbances occur makes it easier to prepare for subtle environmental changes that impact communication signals, navigation systems and orbital mechanics.

Such effects are rarely visible to ground-based observers but are critical for spacecraft operating in low Earth orbit. The ability to monitor them continuously from space enhances resilience in space infrastructure and improves models of atmospheric dynamics.

The findings from AWE may also contribute to broader studies of space weather, particularly in how disturbances in Earth’s atmosphere propagate upward and interact with charged particles in the ionosphere and magnetosphere. These interactions can affect radio waves, satellite communication and GPS accuracy.