New York

—

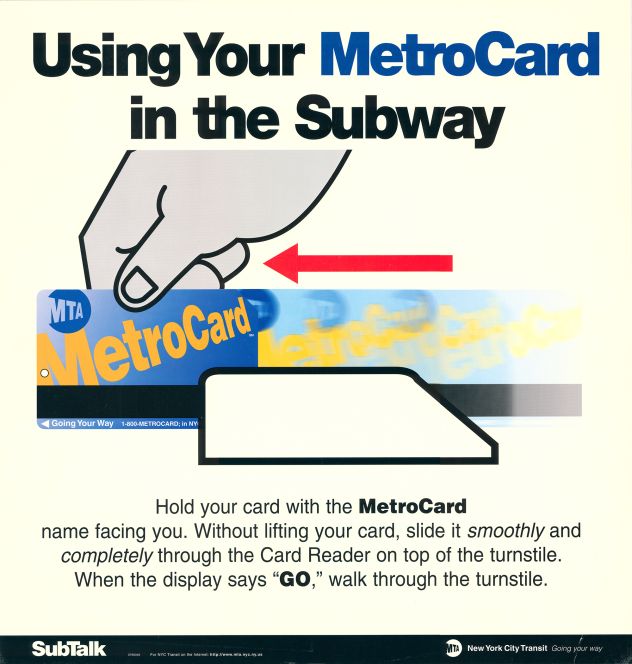

For more than three decades, lifelong New Yorkers and tourists visiting the Big Apple have shared the experience of a MetroCard swipe gone wrong. Swiping the transit card too fast or too slow, with the stripe facing the wrong side, or having insufficient fare all led to the subsequent, seemingly judgmental thud of the turnstile slamming into you.

“It’s embarrassing. You feel like you’re not an authentic New Yorker if you’re not swiping your MetroCard the right way,” said Mike Glenwick, 37, who has lived in the city most of his life and has been collecting limited-edition MetroCards since he was six.

Now the days of swiping the blue and yellow plastic cards are numbered. Come January 1, the Metropolitan Transit Authority will no longer sell MetroCards, and riders will be required to use OMNY, a contactless fare payment system. (Existing MetroCards will continue to be accepted at terminals, though MTA said their “final acceptance date will be announced at a later time.”)

Bidding farewell to the card has been a journey for New Yorkers and the MTA alike.

New York City subway’s iconic tokens were the default form of fare payment before the MetroCard was introduced. When tokens were initially rolled out in 1953, they were about the size of a dime and most had a hollowed-out Y between an engraved N and C, spelling out NYC.

Though clunky to carry around, they were easy to use: all transit passengers had to do was drop the tokens into a turnstile or farebox. For the MTA, it overcame the issue of being able to increase fares without having to redesign fare collection systems to accept various kinds of coins.

But in 1983 Richard Ravitch, then the commissioner of the MTA, began to envision a different fare payment system. Instead, he floated a magnetic stripe card with a stored value.

“His argument was that New York is a very modern cosmopolitan city and there are other modern cosmopolitan cities that are using this as their fare payment system,” said Jodi Shapiro, curator of the FAREwell MetroCard exhibit at the New York Transit Museum. But as his idea gained traction, it quickly became about more than just keeping up with other cities. At one point the MTA considered integrating MetroCards with pay phones so callers didn’t have to use coins (that didn’t end up happening, though).

The MTA initially thought the shift to MetroCards would “spell the death knell for fare evasion” since many riders were previously getting away with using various other kinds of coins and tokens, said Noah McClain, a sociology professor who has researched MetroCard technology and fare evasion trends. But that was hardly the case: “Fare evasion certainly endured, albeit often in different forms.”

One famous one, “swipers,” as they came to be known, sold bent MetroCards that allowed riders to fraudulently bypass turnstiles. Separately, a group of hackers was able to successfully reverse engineer many parts of the MetroCard.

But riders saw benefits, too. One of the biggest selling points for the MetroCard was that users could purchase different, more flexible fares. That included discounts for seniors, disabled people and students, as well as cards that offered unlimited rides throughout the month.

Cards also came with a massive perk that tokens didn’t: free transfers. One swipe of a MetroCard on a bus or subway meant riders didn’t have to pay again if they transferred to another bus or subway train.

But just as New York subway tokens became icons of the city, so did the MetroCard. And that was by design.

“MetroCards were made to be collected,” Shapiro said. The year the MTA launched the MetroCard, 1994, was also when it released an inaugural limited edition card. Since then there have been around 400 commemorative MetroCards issued. Some of those have featured advertisements, a major source of revenue for the MTA, while others have commemorated historic events, such as Grand Central’s centennial anniversary and the first game between the Yankees and Mets in 1997, a tradition now known as the “Subway Series.”

Other notable cards include the Supreme-branded ones and the David Bowie ones aimed at marketing a museum exhibit timed to the release of cards. New Yorkers reported hours-long lines to purchase these at stations.

Glenwick has nearly 100 MetroCards in his collection, and his first featured members of the New York Rangers after the team won the Stanley Cup in 1994 for the first time in 54 years.

The idea to collect MetroCards immediately clicked for him: “It was something that was accessible to collect. I didn’t spend extra money because we used the MetroCards anyway,” he said.

Thomas McKean has lost track of how many MetroCards he’s accumulated over the past 25 years. It all started on a subway ride where he forgot to bring a newspaper or a book, something he’d typically do before the age of smartphones.

In their absence, to pass the time, he stared at his MetroCard, idly wondering how many words he could wring from its letters. When he got off the subway, he grabbed a fistful of MetroCards lying around on the ground of the station, and once he got home, he started making MetroCards with different words.

“And then without even realizing it, I got hooked because I love the material and aesthetic,” McKean told CNN. His designs were initially two-dimensional, using the front and back of MetroCards cut up and pieced together like a mosaic, but eventually he started experimenting with three-dimensional designs, too.

McKean’s art has been featured at home goods store Fishs Eddy in Manhattan, as well as on the cover of a Time Out New York magazine. His art will also be featured at an upcoming exhibit at the Transit Museum’s Grand Central gallery. Over the years, he’s taken on several commissions. To his surprise, many of those customers aren’t based in New York and yet they exhibit the same admiration for the MetroCard as lifelong New Yorkers.

McKean said he has several thousand untouched MetroCards left in his reserves in addition to all the scraps from prior projects. “I never throw anything away until it’s just too small to use.”

A tap-and-go future

The transit system going forward, OMNY, short for One Metro New York, replaces swipes with taps at turnstiles via smartphones or smartwatches with mobile wallets, credit cards or OMNY cards.

For now, riders can still use cash to purchase OMNY cards for $1 at vending machines at subways and at retailers across the city. But many feel as though it’s a matter of time before the MTA stops accepting cash, like many retailers have, which has essentially excluded people who are unbanked and lack a credit or debit card. (The MTA didn’t respond to CNN’s request for comment.)

“While there’s no doubt the MetroCard will remain an iconic New York City symbol, tap-and-go fare payment has been a game changer for everyday riders and visitors, saving them the guessing game on what fare package is most cost efficient for their travels and making using NYC’s transit system much easier,” MTA chief customer officer Shanifah Rieara said in a statement in March, when the phaseout of the MetroCard was announced.

At the time, the MTA said the change will save the agency $20 million annually “in costs related to MetroCard production and distribution; vending machine repairs; and cash collection and handling.”

But for all the benefits that the MTA has advertised OMNY contains, including unlimited rides after your 12th of the week, Glenwick is not ready to make the transition.

“I feel like part of my childhood is disappearing… I don’t want to let it go until I have to.”