In a remote sector of deep space, researchers have identified something unexpected — a signature that hints at molecular complexity on a scale rarely seen.

The signal originates from a location more than 12 billion light-years from Earth, placing it at a time when the universe was still young and formative. It comes from a source astronomers have studied for years, but recent observations revealed something new.

Data collected from multiple observatories across the globe confirmed the presence of a familiar but extraordinary compound. This detection, made under physical conditions once thought to be too extreme, now reshapes how scientists view the emergence of chemical building blocks in the early cosmos.

A Massive Reservoir Hidden in Plain Sight

The discovery centres on quasar APM 08279+5255, a powerful galactic nucleus fuelled by a supermassive black hole estimated to weigh 20 billion times more than the Sun. Quasars are some of the brightest and most energetic objects in the universe, typically located at the heart of distant galaxies.

This particular quasar lies so far away that its light began travelling toward Earth more than 12 billion years ago, when the universe was less than 10 percent of its current age. Despite its distance, APM 08279+5255 has drawn attention for years due to its extreme luminosity.

Recent analysis by teams at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Caltech has revealed that this quasar is surrounded by a colossal cloud of water vapour. The quantity is staggering: the equivalent of 140 trillion times the volume of all Earth’s oceans.

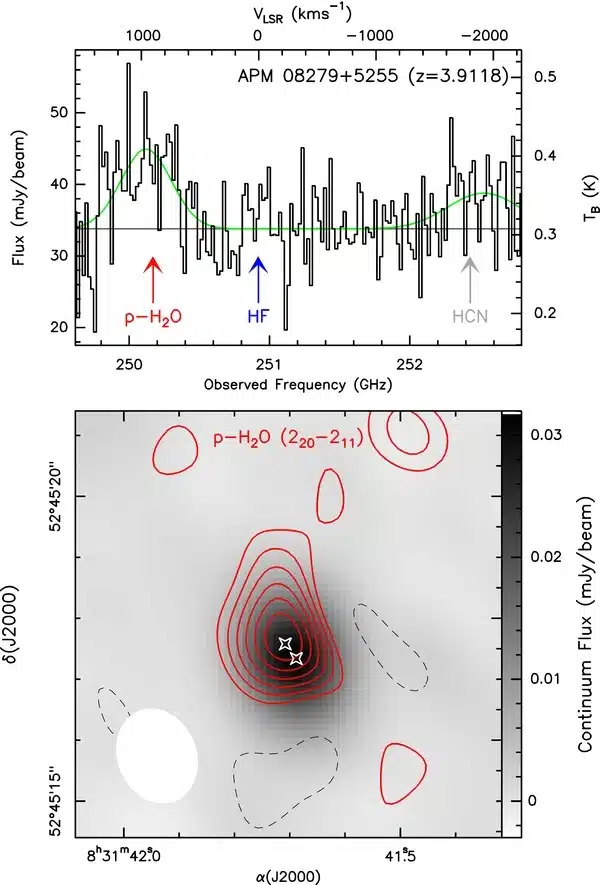

The top panel shows the observed spectrum of the distant quasar APM 08279+5255, highlighting a clear detection of water vapor (marked in red) at a specific frequency. Other molecular lines like HF and HCN are not detected. The bottom panel maps where the water emission is located (red contours), overlaid on an image of the quasar’s dust emission. The strongest water signal is concentrated near the quasar’s center. Credit: Astrophysical Journal Letters

The top panel shows the observed spectrum of the distant quasar APM 08279+5255, highlighting a clear detection of water vapor (marked in red) at a specific frequency. Other molecular lines like HF and HCN are not detected. The bottom panel maps where the water emission is located (red contours), overlaid on an image of the quasar’s dust emission. The strongest water signal is concentrated near the quasar’s center. Credit: Astrophysical Journal Letters

The presence of water was confirmed using multiple instruments, including the Z-Spec spectrometer at the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory in Hawaii, and the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-Wave Astronomy (CARMA) in California. A separate group led by Caltech physicist Dariusz Lis also identified a single water signal in 2010 using the Plateau de Bure Interferometer in France.

Physical Conditions Beyond Expectations

The quasar’s immediate surroundings, where this water vapour exists, are unlike the environments typically associated with molecular gas. These regions are characterised by intense radiation, strong gravitational forces, and elevated temperatures.

Measurements suggest that the water-bearing gas cloud maintains a temperature around minus 63 degrees Fahrenheit. While this would be considered cold by Earth standards, it is hotter and denser than similar interstellar gas found in the Milky Way or other local galaxies. The gas is roughly 300 trillion times less dense than Earth’s atmosphere, yet still unusually dense for such a distant cosmic environment.

In addition to water, researchers identified carbon monoxide, a molecule commonly used to trace interstellar gas. The coexistence of water and carbon monoxide in such quantities suggests the region contains chemically enriched material capable of fuelling black hole growth, triggering star formation, or dispersing into the broader galaxy.

This profile contradicts earlier assumptions that water in space primarily forms in cool, quiescent molecular clouds, where it helps interstellar gas collapse to form new stars. The environment near APM 08279+5255, however, is markedly more active and irradiated, as explained by Earth.com’s detailed coverage.

Rethinking Water’s Role in Cosmic Evolution

The early presence of water in such a location challenges long-held timelines about molecular formation in the universe. Astronomers have generally associated the emergence of complex molecules with more stable, evolved galaxies.

Finding water at this scale and distance indicates that interstellar chemistry developed under a wider range of conditions than models had predicted. It also suggests that the building blocks for habitable environments may have formed earlier — and more often — than previously thought.

Quasars like APM 08279+5255 serve as natural laboratories for understanding the structure and dynamics of the early universe. Their high luminosity allows researchers to study gas flows, chemical enrichment, and galaxy assembly from a vantage point that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Though the detection does not imply the presence of life or planets in this system, it demonstrates that life-supporting elements were present within the first billion years after the Big Bang.

Observations and Future Applications

The research was conducted by scientists from institutions including JPL, Caltech, the University of Colorado Boulder, the University of Maryland, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science in Japan. Funding came from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and supporting research institutions.

Instruments capable of observing submillimetre wavelengths were essential to the detection. These frequencies, located between radio and infrared light, are ideal for capturing molecular signatures in redshifted light from distant sources.

The Z-Spec spectrometer, designed to detect faint emissions from molecules like water, was critical in identifying not just a single line, but multiple transitions in the water spectrum. This confirmed both the presence and the vast scale of the water reservoir.

Future missions, including observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, are expected to extend the reach of such detections. They will target other quasar environments and earlier cosmic epochs, helping to refine current models of black hole evolution, interstellar chemistry, and the physical processes that shaped the early universe.