A groundbreaking study published in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences suggests that a remote rock quarry in Algeria may help scientists detect fossilized life on Mars. The research, led by Youcef Sellam, explores how gypsum, a sulfate mineral found both on Earth and Mars, can preserve microbial life. Using a laser-powered mass spectrometer, the team demonstrated how biosignatures trapped in gypsum could be identified with instruments small enough to travel to Mars. This method may influence how future missions search for evidence of past life on the Red Planet.

Martian Clues Hidden In Algerian Rocks

The Sidi Boutbal quarry in Algeria, a region once submerged under the Mediterranean Sea, has yielded geological conditions strikingly similar to those found in ancient Martian lakebeds. The area, rich in gypsum formed as the sea evaporated over five million years ago, became the center of a detailed astrobiological investigation. According to Sellam, “These deposits provide an excellent terrestrial analog for Martian sulfate deposits.” The presence of gypsum is not just convenient; it’s crucial. The mineral’s ability to trap and preserve microbial filaments makes it an ideal candidate for fossil record retention.

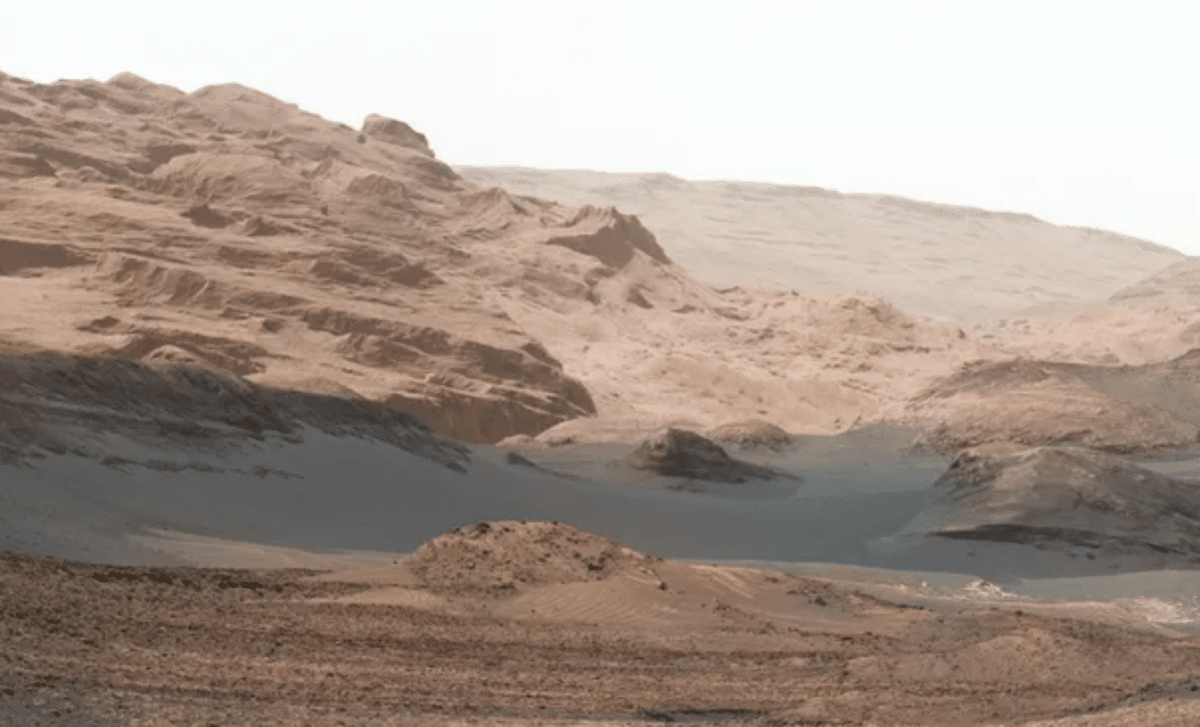

The quarry of Sidi Boutbal, Algeria, where the sampling was carried out. © Youcef Sellam

The quarry of Sidi Boutbal, Algeria, where the sampling was carried out. © Youcef Sellam

The study team uncovered microscopic fossil filaments embedded in gypsum, alongside dolomite, pyrite, and clay minerals, an ensemble often associated with microbial activity. Sellam explained, “One of these minerals is gypsum, which has been widely detected on the Martian surface and is known for its exceptional fossilization potential. It forms rapidly, trapping microorganisms before decomposition occurs, and preserves biological structures and chemical biosignatures.” These findings highlight the importance of mineral context when searching for life. The same types of mineral associations on Mars could point to similar biological processes once occurring there.

The Power Of A Portable Laser

To analyze the samples, researchers used a laser ablation ionization mass spectrometer, a compact and rugged device designed for planetary missions. The laser vaporizes tiny amounts of material from the sample surface, turning it into plasma, which is then scanned to identify the molecular composition. This method enables scientists to look for biosignatures, or chemical fingerprints left behind by life.

Sellam emphasized the significance of the tool: “Our laser ablation ionization mass spectrometer, a spaceflight-prototype instrument, can effectively detect biosignatures in sulfate minerals. This technology could be integrated into future Mars rovers or landers for in-situ analysis.” The ability to bring laboratory-grade analysis to the Martian surface could revolutionize how missions are designed. Rather than just collecting samples for later study on Earth, future missions could evaluate the potential for life on site, refining target areas for sample return or deeper exploration.

The study, detailed in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, shows how the combination of portable instrumentation and mineralogical understanding can guide the design of life-detection strategies in extraterrestrial environments. It’s a leap forward in bringing astrobiology into operational space missions.

Microbial Fossils, Biosignatures, And The Life Detection Challenge

Despite the promise, identifying true biosignatures on Mars remains far from straightforward. “While our findings strongly support the biogenicity of the fossil filaments in gypsum, distinguishing true biosignatures from abiotic mineral formations remains a challenge,” said Sellam. “An additional independent detection method would improve the confidence in life detection. Additionally, Mars has unique environmental conditions, which could affect biosignature preservation over geological periods. Further studies are needed.”

Indeed, the alien nature of Martian microbes, assuming they ever existed, might make their fossilized forms hard to distinguish from non-biological structures. Even on Earth, where scientists know what to look for, verifying biological origins in ancient rocks often demands multiple lines of evidence. On Mars, this complexity is magnified by harsh radiation, chemical weathering, and uncertainty about past environmental conditions.

This is why a multi-instrument approach, combining spectrometry, imaging, and mineralogical analysis, is likely necessary. The integration of tools like Sellam’s laser spectrometer into rover missions could add vital redundancy and increase confidence in any claim of life detection. Instruments aboard upcoming missions like ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover, expected to launch later this decade, may benefit from this methodology.

From North Africa To The Red Planet

Sellam’s study is also notable for another reason. It marks “the first astrobiology study to involve Algeria.” The project bridges geology, planetary science, and biotechnology, highlighting the global nature of space research. It also demonstrates that analog environments are not limited to icy tundras or volcanic deserts. Sometimes they lie hidden in overlooked landscapes, waiting to be reexamined with new questions in mind.

The research also dovetails with the ambitions of NASA’s Perseverance rover, which is currently collecting samples to be returned to Earth. If samples containing gypsum and dolomite are included, their analysis could either confirm or refute the hypotheses developed from Earth analogs like those in Algeria. With the right instruments and frameworks in place, we may soon be able to tell whether life once flourished on Mars or if the search must continue.