When gamma-ray bursts were first discovered by the military, their declassified origin left astrophysicists puzzled. They couldn’t explain how such luminosity could exist. A newly detected burst now challenges what scientists thought they knew.

“There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Shakespeare’s famous line from Hamlet might have crossed the minds of the astronomers behind a recent discovery, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and shared on arXiv.

On July 2, 2025, several instruments detected a gamma-ray burst named GRB 250702B. NASA’s Fermi satellite first spotted it in high-energy rays, triggering a series of observations in other wavelengths — particularly X-rays. Combining data from multiple sources helps scientists better identify the origin of a GRB.

Did you know?

Back in the late 1960s, U.S. military satellites built to detect illegal nuclear explosions unexpectedly recorded bursts of cosmic gamma rays. Scientists overseeing the Vela satellites quickly realized these weren’t human-made events, but cosmic ones. When the findings were later declassified, they astonished the scientific community.

The energy released by these events seemed incomprehensible — until researchers proposed that GRBs were not spherical explosions but narrow jets. This revelation reduced the energy estimates dramatically, though they remained immense, finally making sense within known astrophysics.

Scientists later classified GRBs into two groups: short bursts lasting less than two seconds and long ones lasting around ten. The short type likely comes from neutron star collisions, producing kilonovae — explosions stronger than novae but weaker than supernovae.

Long GRBs, meanwhile, are thought to result from massive, fast-rotating stars collapsing under gravity to form Kerr black holes. These black holes create accretion disks lasting several dozen seconds and produce jets powerful enough to rip through the star’s surface, resulting in hypernovae. This is known as the “collapsar” model — a combination of collapse and star.

Infrared observations using ESO’s Very Large Telescope later pinpointed a distant galaxy where GRB 250702B occurred. To the surprise of astronomers, this gamma-ray burst didn’t last seconds but more than seven hours — the longest ever observed.

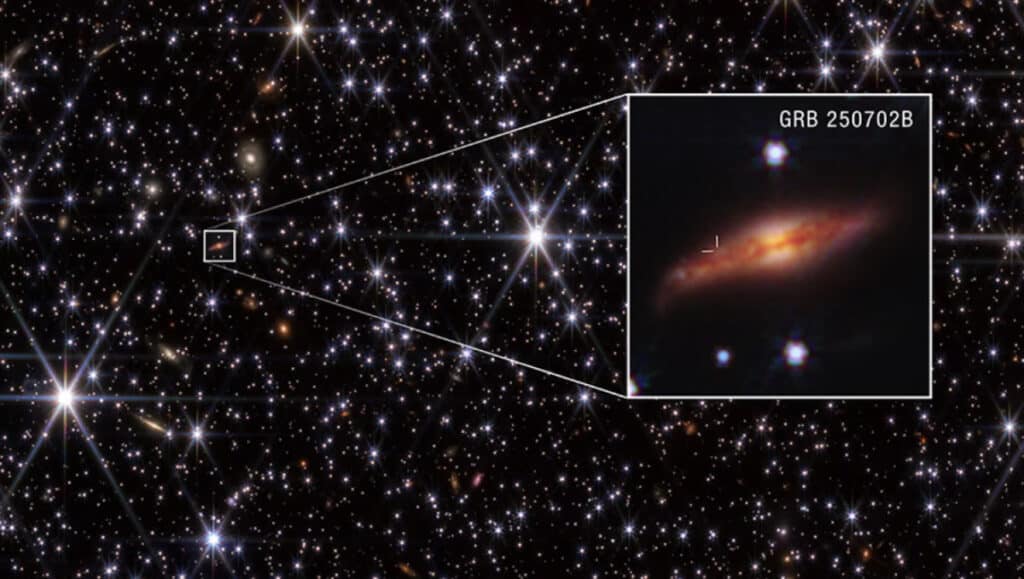

On October 5, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope provided astronomers with the sharpest image ever obtained of the host galaxy of the gamma-ray burst GRB 250702B. This galaxy is so distant that its light takes about 8 billion years to reach us. The burst appears within a field of stars in the very dense central plane of our Milky Way galaxy. In the enlarged image, lines indicate the burst’s position near the upper edge of the galaxy’s dark dust lane. This location rules out the possibility that the burst is linked to the supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s core. The complete infrared image is about 2.1 arcminutes in diameter. © NASA, ESA, CSA, H. Sears (Rutgers). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

A battery of telescopes

A team led by Jonathan Carney, a PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, kept observing the event for 18 days using some of the world’s most powerful telescopes: the 4-meter NSF Víctor M. Blanco Telescope and the twin 8.1-meter Gemini North and Gemini South telescopes of the international Gemini Observatory.

According to a NOIRLab statement, Carney explained, “The ability to rapidly aim the Blanco and Gemini telescopes is crucial for studying transient events like gamma-ray bursts. Without that capability, our understanding of the dynamic night sky would be limited.”

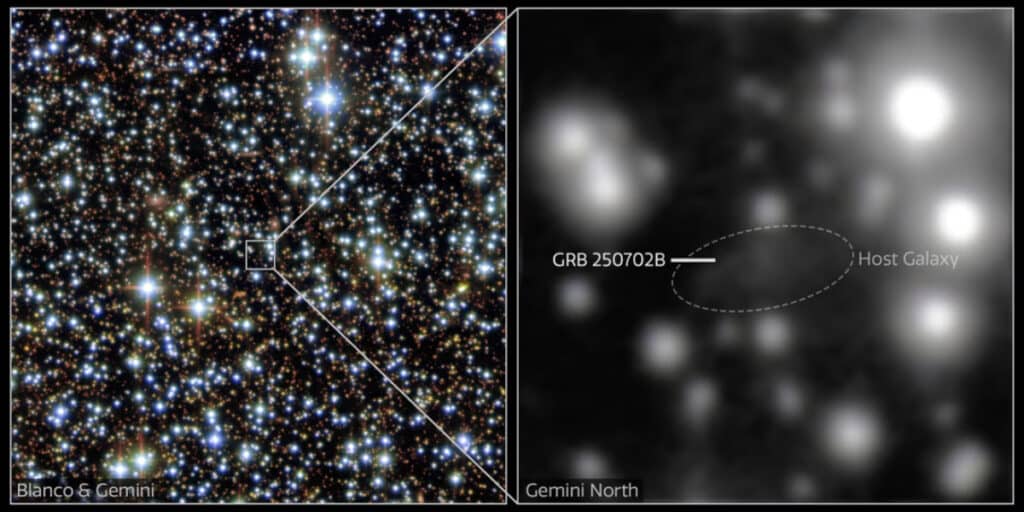

The image on the left shows the star field around the host galaxy of GRB 250702B. It combines observations from the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii and the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), installed on the 4-meter Víctor M. Blanco telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. On the right: a close-up of the host galaxy, taken with the Gemini North telescope. This image, which covers 9.5 arcseconds, is the result of more than two hours of observations. The host galaxy is barely visible, however, due to the thick layer of dust surrounding it. The optical and near-infrared data from DECam were acquired on July 3, while the near-infrared observations from Gemini North were made on July 20. © Gemini International Observatory/CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA. Image processing: M. Zamani and D. de Martin (NSF NOIRLab)

The collected data revealed a relativistic jet matching models of long GRBs — where a massive star collapses into a black hole and erupts in an enormous hypernova. Astronomers also detected vast amounts of dust around the jet’s source and found that its host galaxy was far more massive than typical GRB hosts.

A stunning artist’s impression of a hypernova explosion with the formation of a black hole in the parent star. These computer-generated images illustrate the hypernova model, which is expected to account for the majority of long gamma-ray bursts. Before a very massive star explodes, a black hole forms in place of its core, subsequently engulfing the rest of the star. As an accretion disk also forms, with jets of particles emerging from the star’s surface and propagating through the interstellar medium, creating a shock wave. Gamma-ray photon emissions then occur. © Desy, Science Communication Lab

A micro–Tidal Disruption Event?

Data indicate that the GRB originated in a dense, dusty environment — possibly a thick dust lane in the host galaxy aligned with the Earth’s line of sight. Yet these observations don’t fit established models, pushing scientists to consider new hypotheses.

One theory suggests that a star — or perhaps a smaller object like a planet or brown dwarf — was torn apart by a compact object such as a stellar black hole or neutron star, forming a miniature tidal disruption event (TDE). Another possibility involves an intermediate-mass black hole — a type estimated to range from a hundred to a hundred thousand solar masses — ripping apart a nearby star.

If that second scenario is true, it would mark humanity’s first observation of a relativistic jet from an intermediate-mass black hole devouring a star. While more data are needed, current findings support this intriguing possibility.

A TDE occurs when a star passes too close to a supermassive black hole, whose tidal forces flatten it into a so-called “stellar pancake.” The star may explode, with part of its material consumed by the black hole.

The idea was first proposed in the 1970s by Jack Hills, Juhan Frank, and Martin Rees, based on earlier work by Lynden-Bell. In the early 1980s, Jean-Pierre Luminet and Brandon Carter at the Paris Observatory built precise models and simulations, publishing their pioneering studies in Nature (1982) and Astronomy & Astrophysics (1983). Their work showed how tidal forces could compress a star into a pancake-like form.

Carney concluded, “This research opens a fascinating window into cosmic archaeology — reconstructing the details of an event billions of light-years away. These discoveries remind us how much we still have to learn about the universe’s most extreme phenomena and the importance of continuing to imagine what lies beyond.”

Laurent Sacco

Journalist

Born in Vichy in 1969, I grew up during the Apollo era, inspired by space exploration, nuclear energy, and major scientific discoveries. Early on, I developed a passion for quantum physics, relativity, and epistemology, influenced by thinkers like Russell, Popper, and Teilhard de Chardin, as well as scientists such as Paul Davies and Haroun Tazieff.

I studied particle physics at Blaise-Pascal University in Clermont-Ferrand, with a parallel interest in geosciences and paleontology, where I later worked on fossil reconstructions. Curious and multidisciplinary, I joined Futura to write about quantum theory, black holes, cosmology, and astrophysics, while continuing to explore topics like exobiology, volcanology, mathematics, and energy issues.

I’ve interviewed renowned scientists such as Françoise Combes, Abhay Ashtekar, and Aurélien Barrau, and completed advanced courses in astrophysics at the Paris and Côte d’Azur Observatories. Since 2024, I’ve served on the scientific committee of the Cosmos prize. I also remain deeply connected to the Russian and Ukrainian scientific traditions, which shaped my early academic learning.