An international team of astronomers has uncovered subtle but significant signs that the cosmic engines powering quasars, some of the universe’s brightest objects, may have evolved over billions of years. This revelation, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, could reshape a long-standing assumption about how supermassive black holes behave through cosmic time. The findings hinge on an unexpected shift in the relationship between two key types of light: ultraviolet and X-ray emissions.

Quasars And Their Blinding Brightness

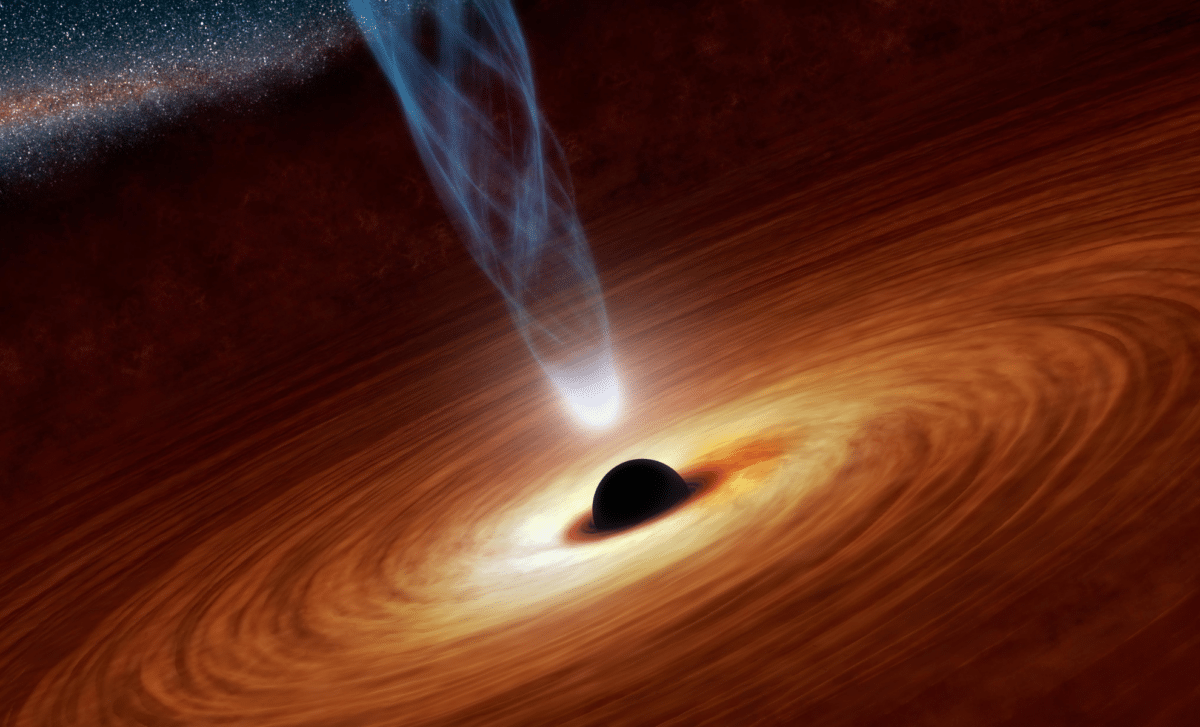

Quasars were first identified in the 1960s and have puzzled astronomers ever since. Powered by supermassive black holes actively accreting matter, quasars emit staggering amounts of energy. As gas spirals into the black hole, it forms a hot, luminous accretion disk that can outshine entire galaxies. The friction within this disk heats the infalling matter to millions of degrees, radiating across the electromagnetic spectrum.

From this glowing disk emerges ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which then interacts with the corona, a surrounding halo of high-energy particles, to generate X-rays. This well-understood UV-to-X-ray process has been remarkably consistent across observations, forming the backbone of many cosmological models.

A Universal Rule That May No Longer Apply

For decades, astronomers assumed a stable correlation between UV and X-ray emissions in quasars, using it to understand black hole environments and even as a tool to map the expansion of the universe. But the new study suggests this correlation may not be as universal as once believed.

Using data from eROSITA and the XMM-Newton observatories, the researchers examined a large population of quasars across cosmic time. They discovered that quasars in the early universe, roughly 6.5 billion years ago, displayed a noticeably different relationship between their ultraviolet and X-ray outputs than those seen in the modern universe.

“Confirming a non-universal X-ray-to-ultraviolet relation with cosmic time is quite surprising and challenges our understanding of how supermassive black holes grow and radiate,” said Dr. Antonis Georgakakis, co-author of the study.

The team employed multiple statistical techniques to validate the anomaly. “We tested the result using different approaches, but it appears to be persistent.”

How Researchers Uncovered The Anomaly

The turning point came with the eROSITA X-ray telescope, whose broad sky coverage provided an unprecedented sample of quasars. While the survey is relatively shallow, it captures a wide array of sources, many of which were only detected with a handful of X-ray photons.

To make sense of this sparse data, the researchers turned to Bayesian statistical modeling, allowing them to detect small yet significant patterns that traditional methods might have missed.

“The eROSITA survey is vast but relatively shallow; many quasars are detected with only a few X-ray photons. By combining these data in a robust Bayesian statistical framework, we could uncover subtle trends that would otherwise remain hidden,” explained Dr. Maria Chira, the lead author of the study.

By integrating eROSITA’s coverage with archival XMM-Newton data, the team created a comprehensive profile of quasars across different epochs. Their findings, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, challenge one of the field’s cornerstone assumptions.

Implications For Cosmology And Black Hole Physics

The implications of these results extend beyond quasar physics. For years, astronomers have used quasars as “standard candles,” cosmic benchmarks for measuring vast distances and investigating the shape of the universe. These measurements rely heavily on the assumption that black hole environments have remained consistent over time.

If the UV-X-ray relationship changes with redshift, then some previous cosmological interpretations may need revisiting. This could have ripple effects on our understanding of dark energy, cosmic expansion, and even the large-scale structure of the universe.

Still, the researchers urge caution. It remains possible that some of the observed variation may be due to observational biases or selection effects.

Future surveys, including upcoming eROSITA all-sky scans and next-generation multiwavelength observatories, are expected to clarify whether this trend reflects true physical evolution or merely methodological noise.