Fusion reactors are designed to produce clean energy, but new theory suggests they could also generate one of physics’ most elusive particles.

A proposal from U.S. researchers argues that large fusion plants may inadvertently create axions – hypothetical particles that could make up dark matter.

The key insight is that the axions would not come from the super-hot plasma where fusion occurs, but from the reactor’s own structure.

According to the new study, fast neutrons released during fusion reactions slam into surrounding metals and lithium.

This triggers rare nuclear processes that could emit axions capable of escaping the reactor and reaching nearby detectors.

The work was led by Professor Jure Zupan at the University of Cincinnati (UC) in Ohio. His research tracks possible dark matter particles, and treats reactor hardware as a new source of axions.

Dark matter remains unseen

Dark matter reveals itself through gravity: galaxies rotate far faster than the pull of their visible stars and gas can account for.

The best measurements show that dark matter makes up about 84.4% of all matter in the universe, dominating the cosmic mass budget.

If axions make up that unseen mass, producing them near reactors could help constrain which theoretical models remain viable.

Axions are difficult to detect

Axions would slip through most materials because they interact only feebly with familiar particles and forces.

Searches often rely on rare conversions into light or electrons, which means even big detectors can wait years.

A clear signal would still need cross-checks, because many models predict related particles that would not make up dark matter.

Fusion reactors release fast neutrons

In a common fusion fuel mix, a helium nucleus stays trapped while a neutron flies out of the plasma.

That escaping neutron carries most of the reaction’s energy, so surrounding structures must absorb a steady beating.

The fusion-reactor axion search proposal depends on this constant bombardment, because it seeds the rare reactions that matter.

Why tritium must be bred

Tritium, radioactive hydrogen that has two neutrons, is scarce in nature, so practical reactors plan to make more during operation.

A 12-year half-life and constant fuel use push designers to breed tritium by letting neutrons strike lithium.

Those same neutron hits can also excite nuclei, setting up the chance to release a new light particle.

Wall capture releases particles

Neutron capture can leave a nucleus in the reactor’s lithium or steel wall materials in an excited state, with excess energy that must be released.

A nuclear transition, an excited nucleus dropping energy by emission, could send out an axion or another light particle.

Because the particle barely interacts, it can pass through shielding and appear just outside the reactor vessel.

Neutron slowing effects

Neutrons that do not get captured can still scatter, losing energy in many smaller collisions inside surrounding structures.

When a charged particle slows down, it emits braking radiation, releasing energy that can give rise to new particles.

The proposal treats this as a second production channel, although it matters most when neutrons keep enough energy.

Particles reach detectors

The proposal relies on these particles traveling tens of feet from the reactor core, far enough to reach detectors positioned outside the reactor structure.

A detector placed 33 feet (10 meters) away could look for interactions that normal neutrons and gamma rays rarely mimic.

Distance matters because the flux spreads out quickly, so experiments need either big reactors, big detectors, or both.

Heavy water detector

The detection concept uses a large tank of heavy water – made with deuterium instead of regular hydrogen – near a fusion facility.

When an axion hits a deuterium nucleus, it can split the pair into a free proton and neutron.

That breakup leaves a clear signature, since the outgoing neutron can be counted and the proton can be tracked.

Fusion reactor signal versus noise

A real test would compare detector rates when the reactor is running with rates when it is shut down.

The biggest background comes from solar neutrinos, tiny particles made in the Sun’s core, that also break deuterium, so timing helps.

Even with backgrounds, the proposal could rule out large slices of parameter space if no excess appears.

Pop culture to physics

In season five of The Big Bang Theory, several episodes tucked the axion puzzle onto whiteboards, with no dialogue explaining it.

“Neutrons interact with material in the walls,” said Professor Zupan. The show’s sun-based math misses the wall reactions, and that is exactly where the proposal finds its advantage.

Limitations of theory

Some production estimates rely on quick scaling arguments, because the exact nuclear reactions in wall materials are not fully mapped.

Better reactor-specific simulations would track where neutrons slow down and which atom types they hit, using measured reaction probabilities.

Until those inputs improve, the proposal can sketch promising reach but cannot guarantee a detectable rate at any single facility.

The future of fusion reactors

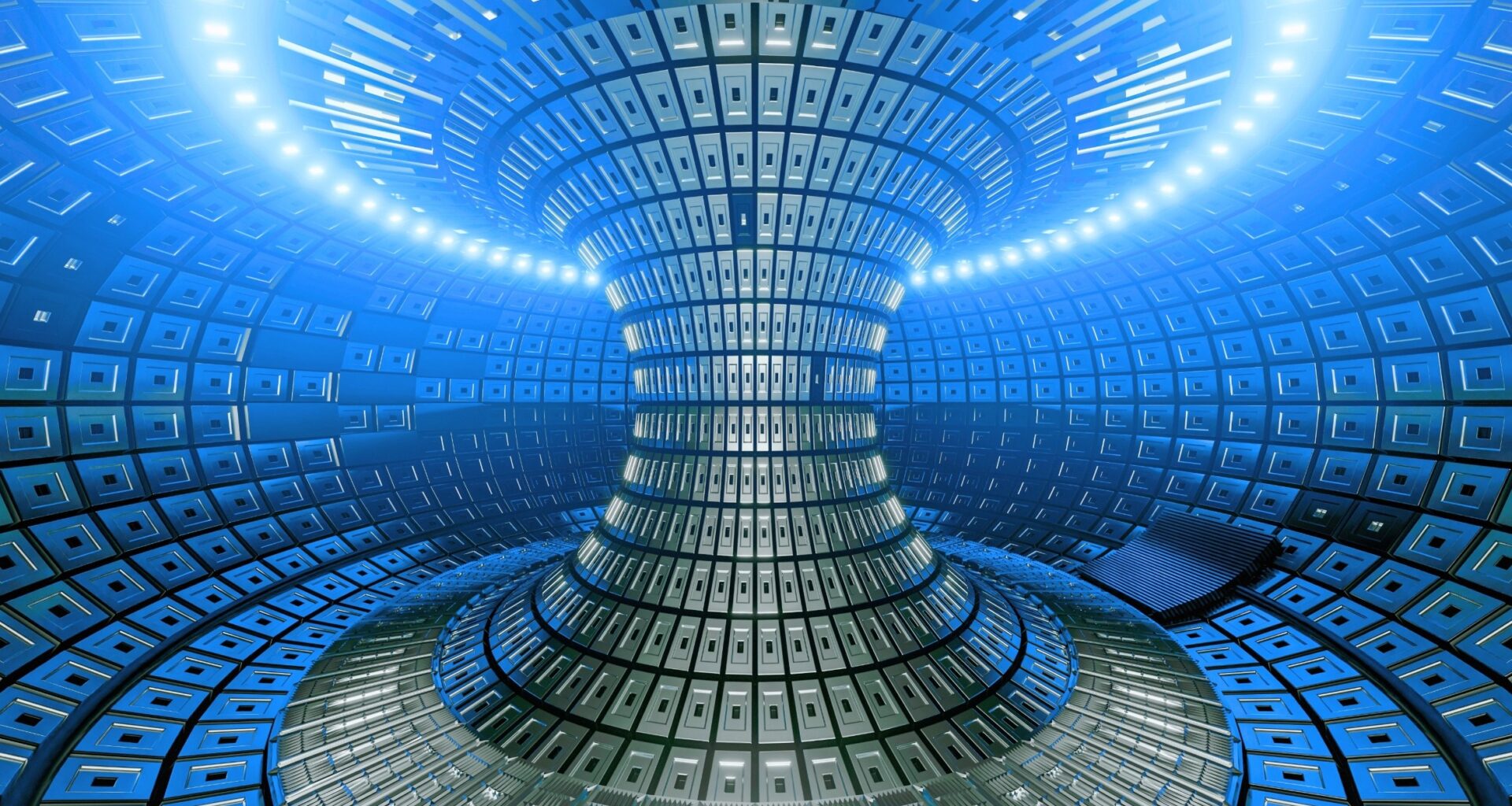

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) site in southern France shows the scale of machines now under construction.

ITER will test key technologies like tritium breeding, and later plants could run longer and produce more neutrons.

If engineers can reserve nearby space for detectors, ITER-class facilities could double as particle laboratories without changing their energy mission.

Neutron-rich fusion linings could become controlled sources for testing one candidate for dark matter directly.

Next, researchers need reactor-specific simulations and detector designs that can confirm or refute the proposal with clear controls.

The study is published in the Journal of High Energy Physics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–