Researchers have identified the deepest known methane seep in the Arctic, located almost 12,000 feet below the surface on Molloy Ridge in the Greenland Sea.

The discovery pushes known hydrate outcrops nearly 5,900 feet deeper than any previously confirmed site and exposes a living system at extreme depths.

Sonar picked up tall methane flares above the ridge – hinting at a cold seep, a seafloor leak of methane-rich fluids.

The work was led by Professor Giuliana Panieri at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, guiding ship sonar toward the plume source.

Her research focuses on methane chemistry and seafloor mapping, and the newly discovered Freya Hydrate Mounds quickly became a priority target for sampling.

Arctic conditions trap methane ice

High pressure and near-freezing water make methane and water lock together, so hydrates can form and survive for long periods.

In the Arctic, cold bottom water widens the hydrate stability zone, the depth band where hydrates stay solid, compared with warmer oceans.

That extra stability lets buried gas move upward through cracks, yet it also sets a sharp boundary where bubbles start dissolving.

Methane rises upward

Ship sonar tracked bubble trains rising more than 10,827 feet (3,300 meters), making them among the tallest methane plumes ever recorded.

As pressure drops during ascent, hydrate skins can peel away, and seawater mixes in to dissolve methane faster.

Because the plume rose to within about 984 feet (300 meters) of the surface, researchers can track how much gas persists.

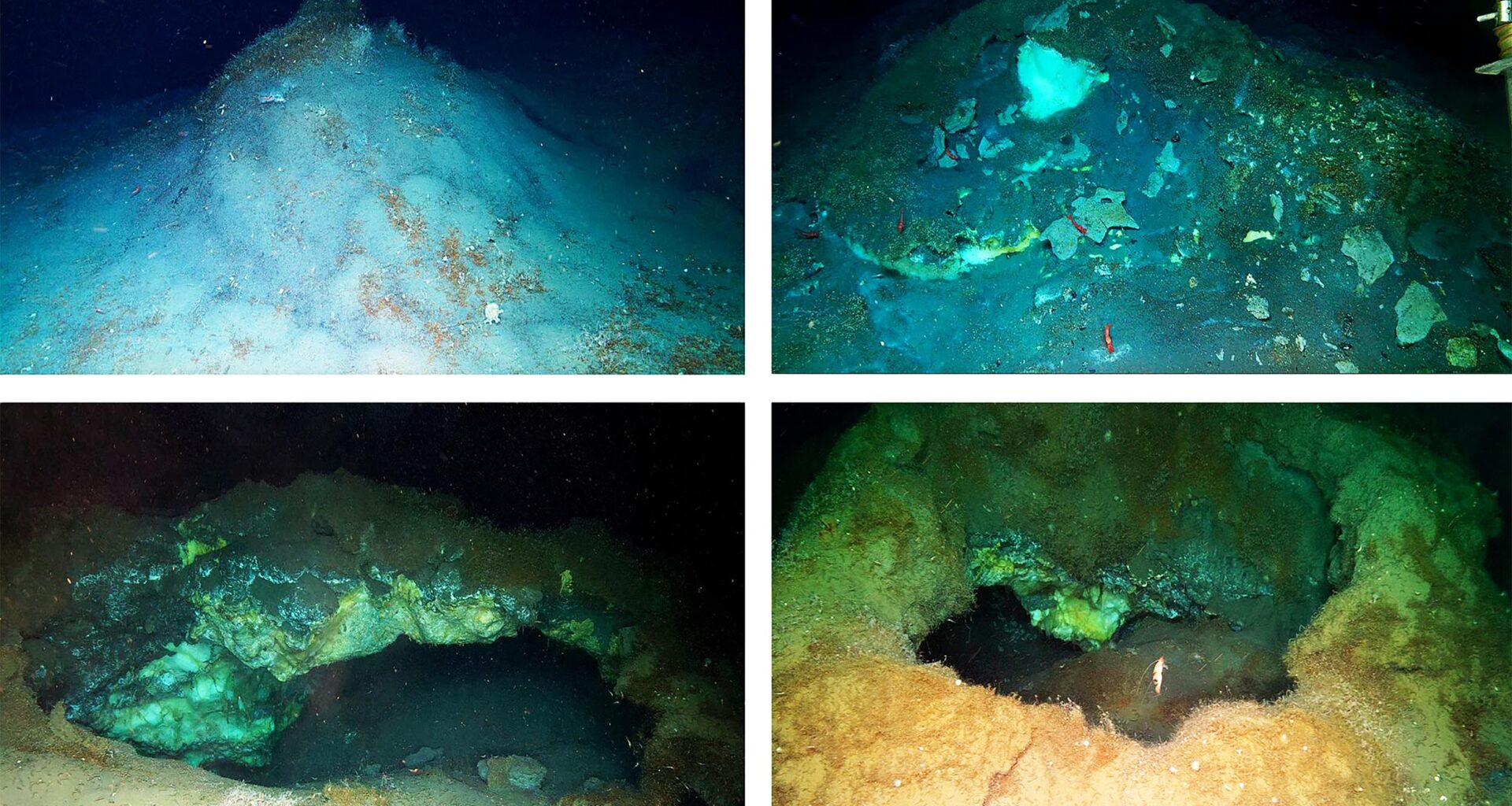

ROV image of a partially collapsed gas hydrate mound in the Molloy Deep (Freya mounds), where exposed gas hydrates are visible beneath sediment cover. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Deep gas origins

ROV image of a partially collapsed gas hydrate mound in the Molloy Deep (Freya mounds), where exposed gas hydrates are visible beneath sediment cover. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Deep gas origins

Gas tests revealed thermogenic gas, methane made by deep heat breaking organic matter, mixed with small amounts of heavier hydrocarbons.

The researchers also sampled crude oil, and chemical fingerprints pointed to Miocene source rocks that formed in fresh-brackish settings.

Those mixed fluids imply long-lived pathways through the ridge, which matters when assessing future drilling or mining disturbances.

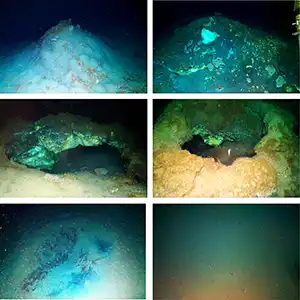

Camera surveys found three conical mounds and two collapse pits packed into roughly 330 by 330 feet (100 by 100 meters).

Some structures showed exposed hydrate at the top, while others had arches and fractures from dissociation, breaking apart as pressure changes.

“These are not static deposits,” noted Professor Panieri, as fractures and pits showed hydrate loss across the mound field.

Exploring the seafloor

Aurora, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), carried cameras and corers to the seafloor.

After the sample box reached the ship, pressure relief triggered rapid bubbling, because the hydrate lattice collapsed and released trapped gas.

That quick breakdown makes collection tricky, yet it also lets analysts capture fresh chemistry before microbes alter the mix.

Life without sunlight

At this depth, no sunlight reaches the bottom, so food webs depend on chemicals leaking from sediment.

Bacteria perform chemosynthesis, making food from chemicals instead of sunlight, and animals tap that energy through symbiosis.

Such communities can cluster tightly around a seep, which means a small patch of seabed can hold outsized diversity.

(A) In situ hydratemound fauna, including Sclerolinum forest. (B) Tube-dwelling maldanid polychaete. (C) Melitid amphipod. (D) Ampharetid polychaete. (E) Stauromedusa Lucernaria cf. bathyphila. (F) Rissoid and skeneid gastropods on a maldanid polychaete tube. (G) Thyasirid bivalve. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Animals thrive near methane

(A) In situ hydratemound fauna, including Sclerolinum forest. (B) Tube-dwelling maldanid polychaete. (C) Melitid amphipod. (D) Ampharetid polychaete. (E) Stauromedusa Lucernaria cf. bathyphila. (F) Rissoid and skeneid gastropods on a maldanid polychaete tube. (G) Thyasirid bivalve. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Animals thrive near methane

Dense fields of siboglinid tubeworms, tube worms that host bacteria inside their tissues, covered mound surfaces in a Sclerolinum forest.

The worms draw methane-fed and sulfide-fed bacteria into their bodies, and those microbes provide nutrients that keep hosts alive.

Snails, shrimp, and amphipods gathered among tubes and carbonate crusts, but the team also spotted collapsed pits with fewer animals.

Deep sea habitats are interconnected

Family-level comparisons linked the seep fauna with hydrothermal vents, seafloor hot springs that vent mineral-rich fluids, farther along the ridge system.

At the Jøtul vent field, about 165 miles (266 kilometers) away, researchers found several individuals of the same worm and snail families.

Because depth, not distance, best predicted similarity, managers may need regional maps that treat deep habitats as linked networks.

Methane rising from the seafloor

Methane leaving the seafloor does not automatically reach the air, especially when bubbles start dissolving high in the water column.

Microbes carry out methane oxidation, turning methane into carbon dioxide, and that process can reduce how much heat it traps.

Even so, tall flares help scientists test how fast those filters work, which matters for Arctic climate projections.

Freya gas hydrate mounds with different morphologies. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Methane hydrates store vast carbon

Freya gas hydrate mounds with different morphologies. Credit: UiT/Ocean Census/REV Ocean. Click image to enlarge.Methane hydrates store vast carbon

Global inventories vary widely, but some estimates place hydrate carbon near 11,000 billion short tons (10^19 grams) worldwide.

Those estimates depend on sonar coverage and on assumptions about how much gas sits inside sediments.

The Freya Hydrate Mounds add a rare deep measurement, which can tighten those ranges and guide monitoring for future change.

“This discovery rewrites the playbook for Arctic deep-sea ecosystems and carbon cycling,” said Professor Panieri.

“We found an ultra-deep system that is both geologically dynamic and biologically rich, with implications for biodiversity, climate processes, and future stewardship of the High North.”

Arctic warming affects methane stability

Methane carries a higher global warming potential, a measure comparing heat-trapping effects, than carbon dioxide over a century.

Because methane persists for about a decade, big leaks can warm quickly, even if they later fade away.

Deep sources like the Freya Hydrate Mounds may still send most methane into the ocean, yet their trends could signal Fram Strait warming.

Human activity in fragile ecosystems

Norway opened parts of its continental shelf for mineral activity, placing rare ecosystems closer to industry interest.

Environmental reviews must weigh deep-sea mining, extracting minerals from seafloor rocks and sediments, against habitats that recover slowly after disturbance.

“Understanding these unique habitats is essential for safeguarding biodiversity and supporting responsible decision-making in polar regions,” said Professor Panieri.

Future surveys in the deep Arctic

The Freya Hydrate Mounds link deep geology, methane chemistry, and unusual animal communities, showing how much of the Arctic seafloor remains unseen.

“There are likely to be more very deep gas hydrate cold seeps like the Freya mounds awaiting discovery in the region, and the marine life that thrives around them may be critical in contributing to the biodiversity of the deep Arctic,” said Jon Copley of the University of Southampton.

“The links that we have found between life at this seep and hydrothermal vents in the Arctic indicate that these island-like habitats on the ocean floor will need to be protected from any future impacts of deep-sea mining in the region.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–