Employees of powerhouse insurance company Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts donated more to Massachusetts’ most powerful elected officials last year than any other company, according to a Globe analysis of campaign finance data.

The top individual donor to Governor Maura Healey and five of the Legislature’s top Democrats in 2024 was the head of Tufts Medicine. And health care and insurance industry officials donated more money to House Speaker Ron Mariano and Senate President Karen E. Spilka’s than executives and employees from any other industry, according to the Globe analysis.

The Globe identified the state’s most frequent and generous donors through a first-of-its-kind analysis of state-level campaign finance data that highlights how powerful business interests dole out campaign donations while seeking, or hoping to prevent, major policy changes.

That political largesse — showcased in scores of both small-dollar donations and maximum contributions, often from a company’s C-suite — underscores what experts say is both the immense influence wielded by the health care industry on Beacon Hill, as well as its dependence on policymakers to set rates, write regulations, and fund programs.

People working in the health care and insurance sectors combined to give $357,000 to those half-dozen political leaders, trailing only two other categories identified by the Globe: those working in real estate and construction, who collectively poured $413,000 into those officials’ accounts, and a broader group that includes hundreds of consultants, lobbyists, and public relations officials who are not tied to one particular business sector.

The health care industry is both a powerful hub in Greater Boston’s identity, economy, and social fabric — and also one of its most fragile.

“The reason is obvious: It’s not a free market,” said Richard Frank, a health care economist who also served on a state commission several years ago that examined medical pricing. One CEO, he said, “never passed up the opportunity to say ‘no margin, no mission‘” — a common term health care executives use to stress that without financial stability, hospitals can’t stay open and provide vital services to the public.

“I don’t view that as being nefarious,” Frank said. “[The health care industry’s] bread is buttered the same way.”

The Globe examined nearly 9,000 contributions made last year to Healey, Mariano, and Spilka, as well as the House’s No. 2 Democrat and the Legislature’s two budget chiefs — a group of lawmakers who exert an outsized influence over what becomes law. With the help of a sorting algorithm, Globe reporters classified each donation within one of more than two-dozen industries, from banking to biotech — a data point not often readily apparent in the state’s campaign finance database.

The Globe’s analysis found that collectively, the six most powerful Democrats raised just under $3 million over the course of 2024. Most of the lawmakers included in the Globe’s analysis also handily won reelection. Their races are rarely competitive, which means they don’t necessarily need the money they rake in to retain their influential seats.

The donations flowed during a busy legislative session that produced several sweeping health care bills, touching everything from midwives to breast cancer screenings to prescription drug costs.

Under Massachusetts’ campaign finance law, corporations and businesses are barred from giving directly to a political candidate or officeholder’s campaign. But individuals who work for them can give up to $1,000 annually, meaning well-heeled executives often help drive the flood of cash politicians rely on to run for office, host parties, or attend dinners.

Collectively, Spilka and Mariano — the Legislature’s top two Democrats — received more than $91,000 from the health care and insurance industries alone, accounting for roughly $1 of every $4 they raised last year, according to the Globe analysis.

Boston’s health care industry is enormously important and complex, helping power the region at the same time many of its major players are also navigating their own financial hardship. Hospitals and insurers can often be on opposing sides of an issue. The ripple effects of just one company’s failure — or in the case of Steward Health Care, its leaders’ potentially criminal actions — can be enormous.

“The employees’ direct donations to political leaders offer another avenue of influence and can help make sure they have a seat at the table,” said Alan Sager, a professor of health law, policy, and management at the Boston University School of Public Health.

“They’re trying to protect their institutions,” Sager said. “They know in a crisis, how state government acts could hurt them — or help them.”

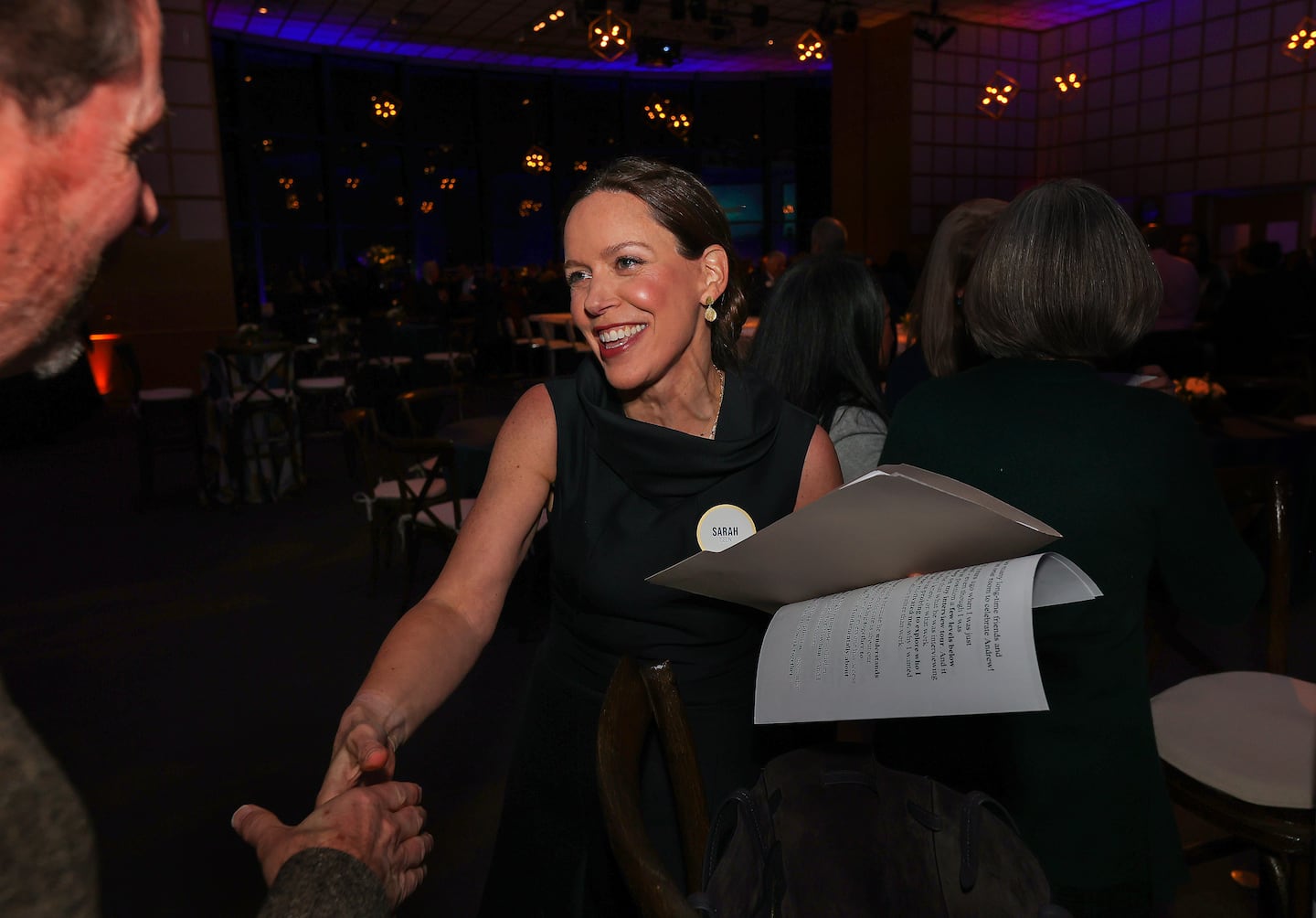

Blue Cross Blue Shield chief executive Sarah Iselin was among nearly 50 employees from the insurance giant to make donations to several of Massachusetts’ top Democrats last year.Barry Chin/Globe Staff

Blue Cross Blue Shield chief executive Sarah Iselin was among nearly 50 employees from the insurance giant to make donations to several of Massachusetts’ top Democrats last year.Barry Chin/Globe Staff

Those working for Blue Cross Blue Shield, Massachusetts’ largest health insurer, collectively gave $36,000 to those six Democrats, outpacing those at any other corporation in health care or any other sector.

About 50 Blue Cross Blue Shield employees accounted for more than 100 contributions, including to state Representative Aaron Michlewitz, state Senator Michael Rodrigues, and House majority leader Michael Moran.

Ruby Kam, Blue Cross Blue Shield’s chief financial officer, gave $3,000 in total to Healey and legislative leaders, as did its chief operating officer, Richard Lynch. Then-vice president and lobbyist Michael Caljouw, who now serves as Healey’s insurance commissioner, also made four $200 donations, the maximum allowed for a lobbyist per candidate. (Caljouw did not respond to questions submitted to him through a Healey spokesperson.)

As Beacon Hill’s leaders weigh far-reaching health care bills, Blue Cross Blue Shield wants to “ensure the voices of our members and employer customers are heard in those discussions,” said company spokesperson Amy McHugh. One way to do that, she said, is to make political donations.

Unlike some major hospital leaders, Blue Cross Blue Shield employees, she said, don’t make contributions through trade groups’ political action committees. The Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association’s PAC, for example, contributed thousands of dollars to lawmakers last year after taking donations from hospital executives it helps represent.

Blue Cross Blue Shield, however, has its own PAC, the Cross and Shield Political Action Committee, which is fueled by donations from several of its top employees. That, too, spread thousands of dollars in donations to lawmakers last year beyond its executives’ personal donations, records show.

McHugh did not make Blue Cross Blue Shield chief executive Sarah Iselin available for an interview. Iselin, who is also a registered lobbyist, donated the maximum $200 to Healey, Mariano, Spilka, and Michlewitz.

“We are proud to advocate for affordability, quality and equity in healthcare,” McHugh said in a statement. “A strong healthcare system is essential to Massachusetts’ future, including our state’s ability to attract and retain businesses and workers.”

Employees at Tufts Medicine and its affiliated hospitals, including Lowell General Hospital and MelroseWakefield Hospital, gave $21,725, the Globe found. Beyond Blue Cross Blue Shield, only those working for WilmerHale, who gave $23,500 to Healey, and Quincy-based Arbella Insurance, which donated a combined $22,800 to the six Democratic leaders, gave more.

Healey worked at WilmerHale for a decade before moving into politics.

No individual gave more than Michael Dandorph, the president and chief executive of Tufts, the nonprofit hospital chain that Dandorph warned in 2024 would need more government help amid deep financial losses.

Dandorph gave maximum $1,000 donations to each of the six elected officials whose campaign filings the Globe analyzed.

Tufts officials declined to make Dandorph available for an interview, instead saying in a statement that employees across the organization “may engage in civic activities,” including making donations.

“Personal contributions by employees, including leadership, are made as private citizens,” the statement said.

Employees from Mass General Brigham and its affiliated hospitals and health plan gave roughly $9,400 to the six Democratic leaders last year, according to state data. Those at Point32Health, the owner of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care and Tufts Health Plan, contributed about $8,800.

Blue Cross Blue Shield has given in other ways in the past, too. The organization chipped in $25,000 to Healey’s inaugural committee, which under state law is allowed to take contributions from corporations. Blue Cross Blue Shield also funneled $150,000 to a campaign that opposed a failed 2008 ballot question that sought to eliminate the state income tax. A decade later, it gave $100,000 to a committee that successfully campaigned against repealing transgender discrimination protections.

Former Steward chief executive Ralph de la Torre was a regular political donor before his resignation last year, and even hosted a fund-raiser at his home featuring then-President Barack Obama.

Many of the leading health care institutions also lobby the same elected officials — a lot. Blue Cross Blue Shield spent $460,000 on lobbyists last year, more than any other corporate spender. The Massachusetts Association of Health Plans, which represents most health insurers outside of Blue Cross Blue Shield, spent $1.3 million, the most of any business group.

“They have a lot of money to throw around,“ Frank, the economist, said. ”It’s not always for the good but it’s not always for the bad, either.”

Anjali Huynh, Yoohyun Jung, and Emma Platoff of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

How we reported this story

The Globe used a machine learning classification model to analyze about 9,000 campaign finance contributions made in 2024 to six top Massachusetts politicians: Maura Healey, Ronald Mariano, Aaron Michlewitz, Michael J. Moran, Michael J. Rodrigues, and Karen Spilka. The contributions data come from the Massachusetts Office of Campaign & Political Finance.

The model sorted donations into 30 different industry categories — ranging from real estate and healthcare to cannabis and consulting — by analyzing the contributor’s name, occupation, and employer. When employer information was vague or unclear, the model ran automated internet searches to better identify the donor’s affiliations. Each contributor was assigned to just one primary industry category based on the most relevant available information. Every prediction made by the model was reviewed and verified by Globe reporters to ensure accuracy.

Matt Stout can be reached at matt.stout@globe.com. Follow him @mattpstout. Samantha J. Gross can be reached at samantha.gross@globe.com. Follow her @samanthajgross. Neena Hagen can be reached at neena.hagen@globe.com.