In advanced chemistry labs and classrooms around the world, one rule has quietly endured for nearly a century. Introduced in the early 20th century, it has been repeated often enough to pass almost without question, shaping how organic structures are imagined, drawn and dismissed.

Yet within this long-standing assumption lies a structural limitation that has defined what chemists consider impossible to make. Its boundaries have rarely been tested in practice, in part due to the difficulty of proving an exception without violating fundamental chemical principles.

Recent research from a team at the University of California, Los Angeles, published in Science, may now force a revision. Their experiments, focused on a class of molecules known for their supposed instability, suggest that the rule’s constraints are not as fixed as once believed.

A New Path Through Structural Strain

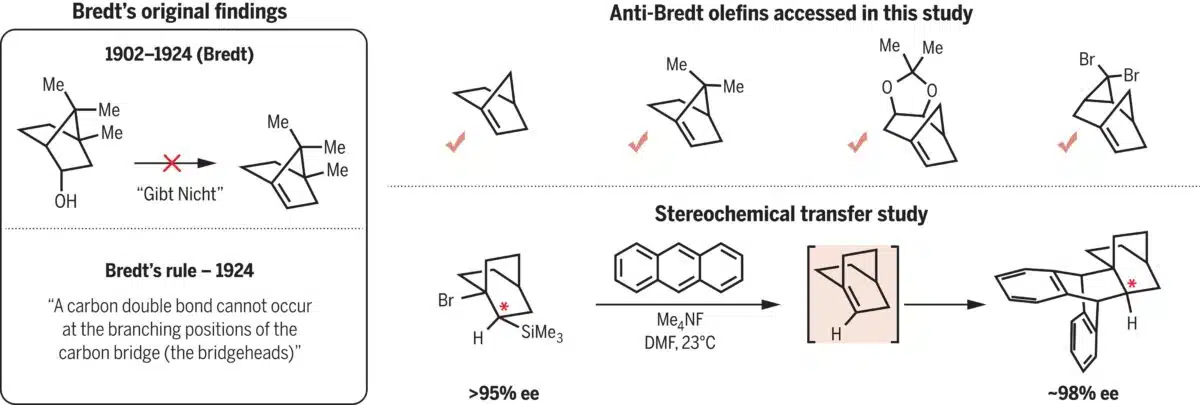

Researchers at UCLA, led by Professor Neil Garg, have developed a method to generate anti-Bredt olefins. These are molecules containing a double bond at a bridgehead position, previously thought to be too geometrically strained to form. Such compounds have long been considered unfeasible due to Bredt’s rule, a principle formulated in 1924 by German chemist Julius Bredt, which holds that these configurations are unstable in small, bridged ring systems.

Bredt’s rule (1924) and anti-Bredt olefins generated in this study. Credit: Science

Bredt’s rule (1924) and anti-Bredt olefins generated in this study. Credit: Science

Using a multi-step chemical sequence, the team avoided isolating the unstable intermediate. Instead, they designed a system where a fluoride ion initiates a fast reaction that forms the forbidden double bond just long enough for it to be captured by another molecule. The result is a stable end product, but one that could only form if the anti-Bredt olefin briefly existed.

While the fleeting intermediates were not directly observed, the chemical evidence pointed clearly to their involvement. In one key experiment, the team used a chiral starting material, a molecule with a defined spatial orientation, and found that the final product retained the same handedness. This outcome, researchers say, is only possible if the reaction passed through the proposed structure.

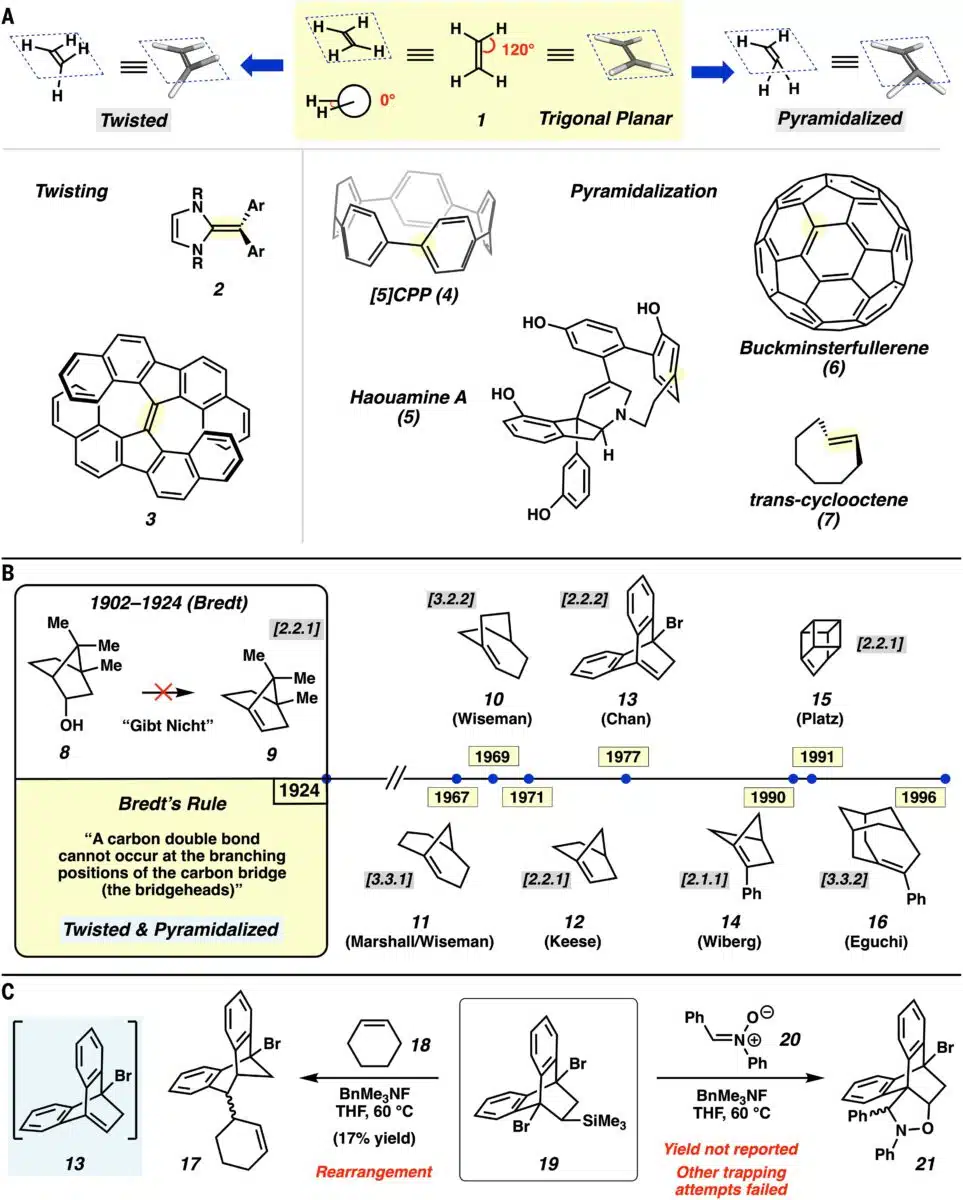

Geometric Distortions Of Unsaturated Compounds And Historical Perspective Of Anti Bredt Olefins. Credit: Science

Geometric Distortions Of Unsaturated Compounds And Historical Perspective Of Anti Bredt Olefins. Credit: Science

Computational simulations supported the results, aligning with the lab observations and confirming that such high-strain intermediates could, under the right conditions, be both formed and used synthetically.

“People aren’t exploring anti-Bredt olefins because they think they can’t,” Garg said, according to Earth.com. “What this study shows is that contrary to one hundred years of conventional wisdom, chemists can make and use anti-Bredt olefins to make value-added products.”

How Bredt’s Rule Shaped Generations of Chemists

Bredt’s rule, now a core concept in structural organic chemistry, emerged from studies of ring strain and geometric limitations in bridged bicyclic molecules. It states that placing a double bond at the bridgehead atom of such a structure is energetically prohibitive unless the ring size exceeds a certain threshold.

For decades, this principle has been treated as a rule of exclusion. Molecules that appear to violate it have been categorised as “anti-Bredt” and considered artefacts of theoretical drawing rather than viable chemical species. As noted in the historical context of Bredt’s work, these conclusions were based on both structural reasoning and the lack of empirical examples.

![Structural Analysis Of [2.2.1] Abo 12 And Synthesis Of A Precursor For Abo Generation](https://www.europesays.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Structural-analysis-of-2.2.1-ABO-12-and-synthesis-of-a-precursor-for-ABO-generation-600x1200.jpg.web.webp) Structural Analysis Of [2.2.1] Abo 12 And Synthesis Of A Precursor For Abo Generation. Credit: Science

Structural Analysis Of [2.2.1] Abo 12 And Synthesis Of A Precursor For Abo Generation. Credit: Science

The UCLA study does not disprove the rule in general. It reveals that exceptions are possible in dynamic systems where unstable species can form transiently and react before breaking down. This distinction reframes the rule as a reliable generalisation rather than a physical absolute.

“This is not a tiny correction,” Earth.com reported. “It is like learning that you can divide by zero under narrowly defined conditions.”

In practical terms, the work opens new possibilities for working with strained ring systems. It also offers a framework for re-examining other long-standing limitations in chemical synthesis that may be bypassed using similar strategies.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Molecular Architecture

The ability to generate three-dimensional molecular scaffolds has direct relevance for drug discovery, where molecular shape strongly influences binding efficiency and biological activity. Many existing compounds, particularly those that are flat or symmetrical, fail to interact optimally with complex biological targets such as enzymes, receptors or transport proteins.

![Scope Of Trapping Reactions With [2.2.1] Anti Bredt Olefin 12](https://www.europesays.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Scope-of-trapping-reactions-with-2.2.1-anti-Bredt-olefin-12-1200x1154.jpg.webp.webp) Scope Of Trapping Reactions With [2.2.1] Anti Bredt Olefin 12. Credit: Science

Scope Of Trapping Reactions With [2.2.1] Anti Bredt Olefin 12. Credit: Science

“There’s a big push in the pharmaceutical industry to develop chemical reactions that give three-dimensional structures like ours because they can be used to discover new medicines,” Garg said in the Earth.com article.

The structures made possible by the UCLA method introduce spatial complexity that could be leveraged to improve molecular interactions in biological systems. As pharmaceutical chemists increasingly pursue “escape from flatland” strategies, such as those described in drug discovery literature, new geometries like these offer a way forward.

Beyond pharmaceuticals, the same molecular frameworks may find application in advanced materials, functional polymers and catalysis, where geometry and stability determine performance. Designing systems that accommodate or briefly stabilise reactive intermediates could help improve selectivity and control in industrial chemistry.

Rewriting the Role of Rules in Chemical Education

The broader significance of the study lies in how chemical rules are framed and applied. For many students, rules like Bredt’s are taught as firm constraints on molecular structure. The UCLA findings present a case for treating such principles as flexible models rather than strict boundaries.

“We shouldn’t have rules like this – or if we have them, they should only exist with the constant reminder that they’re guidelines, not rules,” Garg said. “It destroys creativity when we have rules that supposedly can’t be overcome.”

Interest in replicating and expanding the work is growing. Labs in the US and Europe are reportedly adapting the reaction sequence for different systems, while materials scientists are considering its utility for building reactive intermediates in semiconductors, bioactive materials and high-performance coatings.