An interior staircase (right) connects two levels of the lower duplex.

Photo: Helen Street

There’s a row of five-story buildings off Fifth Avenue in Park Slope that seem to fit the neighborhood standard for prewar, working-class tenements — a central staircase divvying up ten dark railroad apartments. But 676 Union Street breaks the pattern. There is no central door but rather two on either side of a pair of windows. The door on the left leads up to two massive duplexes, stacked on top of each other, which each stretch the width and length of the building — 25-by-52 feet — giving the units about as much square footage as a small townhouse. The door to the right leads to what is maybe the building’s most intriguing feature: a 25-by-52-foot great room designed to serve as a shared art studio.

676 Union Street.

Photo: Helen Street

The building was created by two couples who met in the early 1980s, after the mayor announced a program to help artists take over abandoned apartment buildings. There were lots of meetings, and lots of interested artists, but the program never took off. Garrick Dolberg liked the idea enough to try doing the work on his own. In 1981, he was a sculptor with a day job in construction. His partner, Elisa Amoroso, was showing moody, Turner-esque landscapes but had studied architecture at Cooper Union. If buildings really were that cheap, maybe they could join up with another couple and try to hack it on their own. Charles Powell and Diana Meckley-Powell were interested. He had a day job in construction, too, and showed abstract paintings, while she made avant-garde musical compositions. “We were all kind of in the same position,” says Amoroso. They pooled their money, and went shopping.

Amoroso and Dolberg.

Photo: Courtesy Elisa Amoroso and Garrick Dolberg

Buildings in Manhattan were out of their budget, so they focused on Brooklyn. 676 Union was vacant, like a lot of buildings around Fifth Avenue at the time. The street was known as a mini-Amsterdam for drug dealers, overlooked by the cops, and Fourth Avenue was home to tire shops and mechanics. There were burned and vacant buildings nearby; landlords had been accused of torching properties, even with tenants inside, to get insurance payouts. 676 was listed for $100,000. The couples put in $50,000 each.

“I don’t think any of us were trying to make an architectural statement in any way,” says Amoroso. But they were envisioning a way to squeeze a Soho loft into a Brooklyn tenement — which wasn’t exactly standard. Together, they drafted a simple design that pulled the central staircase to one side, leaving four windows in back and four windows in front unimpeded. They took down walls but didn’t touch load-bearing columns. To save money, they stacked bathrooms and kitchens above each other. But the architect they hired to sign off on their plans was always shaking his head. “I do remember arguing with him,” says Amoroso. Still, she was unwilling to live in a small, dark apartment building, maybe because she had grown up in one — a three-family building in Chicago packed with her grandparents on the lower level, her aunts and uncles upstairs and down. “I don’t care about things,” she says. “I care about space.”

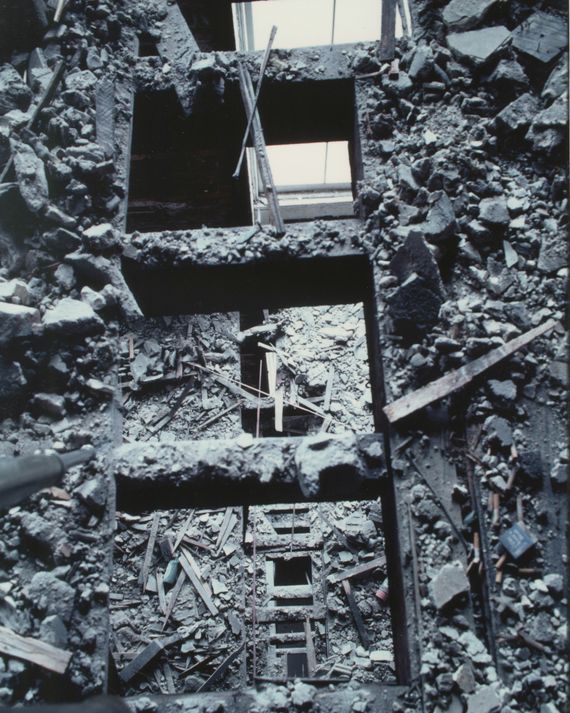

The view up through the gutted building.

Photo: Provided by Elisa Amoroso and Garrick Dolberg

Powell and Meckley-Powell wanted the upper unit because they liked the idea of expansive views and easier access to the roof deck. That worked out for Amoroso and Dolberg, who had dogs and wanted fewer stairs when they took them on walks. They agreed to a tenants-in-common agreement — the easiest way for a group to buy what was registered as a multifamily building, Amoroso says. The split was even, and they paid in cash with a shared $50,000 loan for construction, which “seemed to go on and on and on,” Dolberg says. They hired workers but also pitched in as laborers to gut the five-story building, then laid brand-new hardwood floors in the duplexes and added skylights to the top floor — more light for Powell’s studio. One fireplace was left in the living areas of each duplex unit, and others were covered over, their greenish stone hearths repurposed as exterior steps. The ground floor had been a storefront, and they bricked it over to match the rest of the building. “We tried to make it look residential,” says Dolberg.

A certificate of occupancy came in 1987 and they moved in. They kept the roof and backyard communal, along with the art gallery: Anyone could wander down and make something, or clean it up to turn it into an impromptu show space when a buyer came through — like the time Edward Albee came to buy a Dolberg piece. The Metropolitan Museum of Art bought one, too: a brass form that looks like a pyramid from one angle, but reveals itself to be a false front, like the set of a western movie, with legs propping it up — a visual trick that’s not too different from the old tenement that Dolberg turned into luxury housing. Amoroso showed her work at various galleries that always seemed to go under and found jobs working for other artists and as a graphic designer for an architecture firm, sketching signage. Dolberg’s galleries went under, too, and he took up a hobby building harpsichords. “We got disillusioned but kept making art,” Amoroso says. They had the space, after all.

Powell and Meckley-Powell had a child and added walls to make another bedroom. No one ever took in renters, though when Amoroso’s mother got sick, she took her in; a gift she could give, thanks to the square footage. Nieces and nephews visited for longer and longer stretches, grateful for a cool aunt and uncle in a neighborhood with Southpaw a few blocks away. But the couples are now all in their 70s. Powell and Meckley-Powell moved out this fall. Amoroso and Dolberg like the idea of moving to Italy — where her family is from and where Amoroso has citizenship. “We want to change our lives,” she says. “The initial idea was we could sell if we wanted to, and we never got around to it.”

The bricked-over storefront. The door on the left goes up to the duplexes, and the one on the right goes into the gallery.

Photo: Helen Street

The art-gallery space on the ground floor, with a harpsichord, of course.

Photo: Helen Street

Off to the left of the gallery space, in the back of a hall that leads up to the duplexes, is a small kitchenette that makes it easy to entertain on the patio out back without hiking up and down the stairs. Firewood and a massive CD collection show how they used the place.

Photo: Helen Street

The door to the second floor opens into a space that’s almost entirely open, with a kitchenette (left) and Amoroso’s painting studio (right).

Photo: Helen Street

The studio where Amoroso has been working steadily since 1987.

Photo: Helen Street

On the other side of the studio is a living area. The couple blocked it off with screens to create a bedroom for visiting relatives who sometimes stayed as long as a year.

Photo: Helen Street

An interior staircase leads up to the third floor. Dolberg added the bookcase (right) and other details after receiving the 1987 certificate of occupancy.

Photo: Helen Street

The couple used the space to host concerts for friends, sometimes with a harpsichordist who played one of the instruments that Dolberg learned to build.

Photo: Courtesy Elisa Amoroso and Garrick Dolberg

Upstairs is an open living and dining area

Photo: Helen Street

The kitchen.

Photo: Helen Street

Dolberg added built-ins (right) and a pantry just off the kitchen area.

Photo: Helen Street

The living area with an original fireplace.

Photo: Helen Street

The fireplace. Notice the greenish stone matches the steps outside, which were made with stone from fireplaces on other floors.

Photo: Helen Street

The artists never fussed over the space, which has the aesthetic of a Soho loft in prime Park Slope.

Photo: Courtesy Elisa Amoroso and Garrick Dolberg

In the rear of the same level overlooking the garden is the primary bedroom.

Photo: Helen Street

Dolberg put French doors he sourced for free in a second bedroom, now staged as a media room.

Photo: Helen Street

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related