A newly found world has joined the growing catalogue of known exoplanets, yet its basic properties appear to contradict long-standing astrophysical models. The planet is large, composed mostly of gas, and orbits a star hundreds of light-years from Earth. That much fits within expectations.

What sets it apart is the size of the star it orbits. Unlike the type of stars typically associated with gas giants, this one is exceptionally small and dim. The planet, on the other hand, is far from modest in scale.

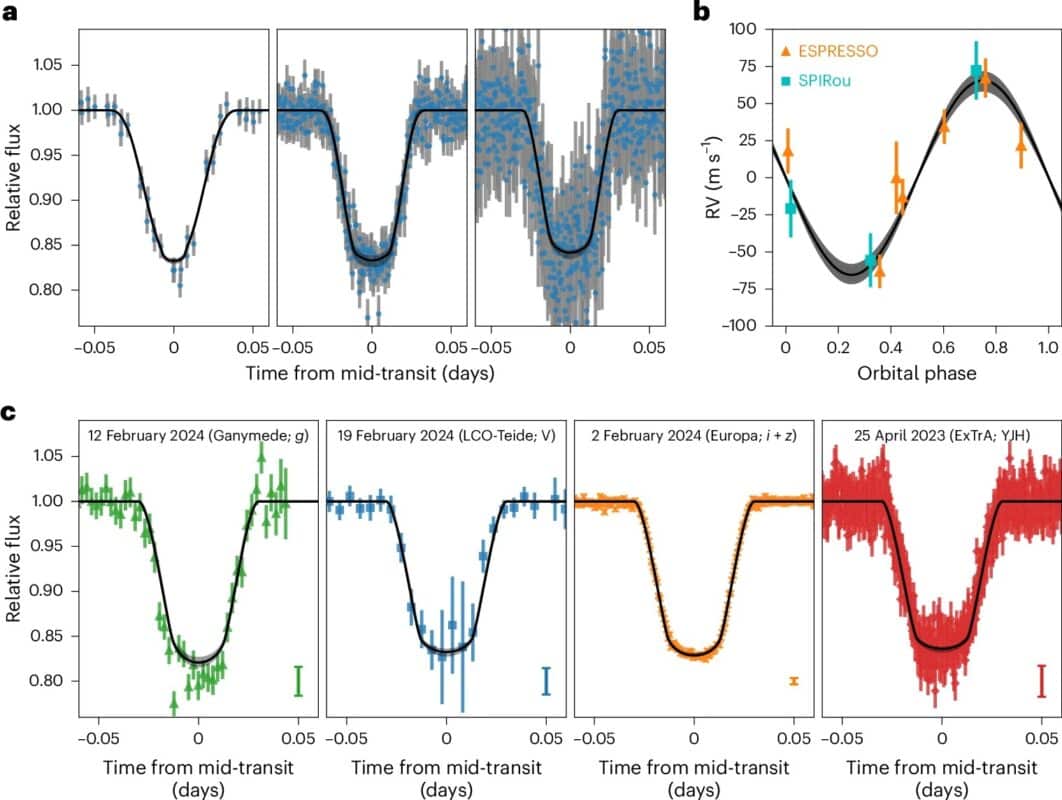

Initial data from space-based telescopes flagged the system for closer inspection. Further ground-based observations confirmed the planet’s dimensions and orbital characteristics. The results have left researchers re-evaluating some foundational principles of planetary formation.

Smallest-Known Host for a Gas Giant

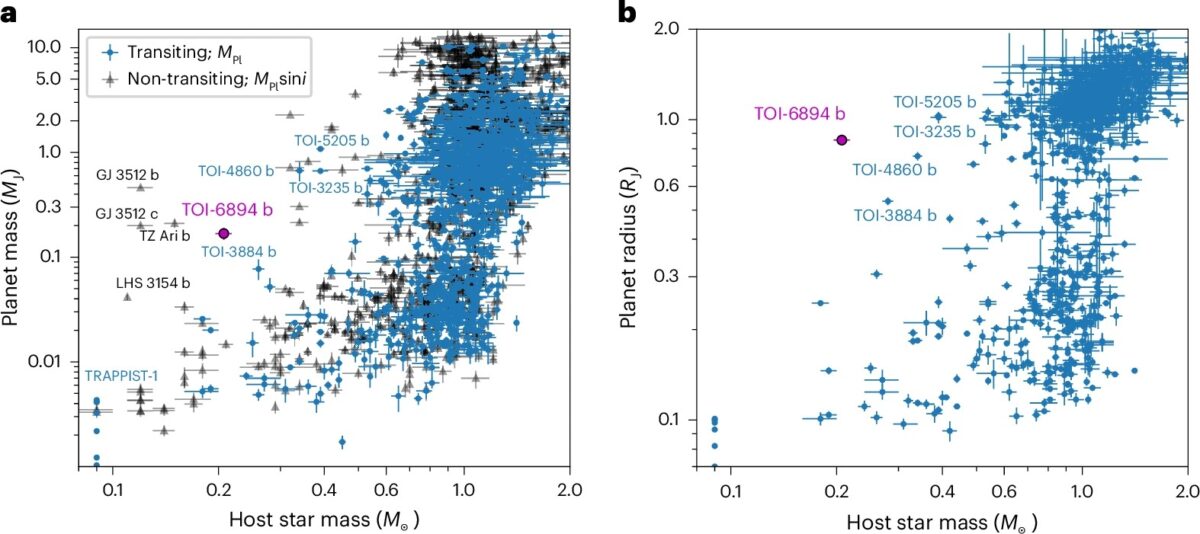

The planet, TOI-6894b, is physically larger than Saturn, although it has only about half that planet’s mass. It orbits a red dwarf star that is roughly 20 percent the mass of the Sun, making it the lowest-mass star known to host a transiting gas giant.

This type of planet is generally believed to form in systems with more substantial protoplanetary disks. The detection of TOI-6894b came through NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), part of an ongoing mission to identify exoplanets around nearby stars.

Follow-up confirmation came from the Very Large Telescope (VLT) operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile, one of the most advanced ground-based telescopes currently in use.

Edward Bryant, lead author and astronomer at University College London (UCL), stated in a report by Earth.com: “We did not expect planets like TOI-6894b to be able to form around stars this low-mass. This discovery will be a cornerstone for understanding the extremes of giant planet formation.”

Researchers involved in the study, published in Nature Astronomy, note that the star is 60 percent smaller than any previously known to host a gas giant. This alone places the system well outside the boundaries of what standard models predict.

Formation Models Under Scrutiny

Conventional planet formation theory holds that gas giants arise through core accretion, a process in which solid material coalesces to form a core that then attracts gas from a surrounding disk. This requires both time and material. Smaller stars like TOI-6894 are believed to have thinner, shorter-lived disks, making it difficult to form such large planets before the gas disappears.

The research team explored whether alternative processes could account for the presence of TOI-6894b. One possibility is gravitational instability, where parts of the disk collapse directly into a gas-rich planet. Another involves modified accretion mechanisms in low-mass stellar environments, though neither explanation fully accounts for the observed data.

“This is one of the goals of the search for more exoplanets,” said Vincent Van Eylen, co-author at UCL’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory. “By finding planetary systems different from our solar system, we can test our models and better understand how our own solar system formed.”

Red Dwarfs as Planetary Hosts

Red dwarfs like TOI-6894 are the most common stars in the Milky Way, making up approximately three-quarters of the stellar population. Historically, such stars were not seen as likely hosts for giant planets, due to their limited disk mass and low luminosity. The discovery of TOI-6894b, if not an isolated case, could significantly affect current estimates of planet distribution in the galaxy.

Daniel Bayliss, co-author and astrophysicist at the University of Warwick, stated: “Most stars in our galaxy are actually small stars exactly like this, with low masses and previously thought to not be able to host gas giant planets. So, the fact that this star hosts a giant planet has big implications for the total number of giant planets in our galaxy.”

The system also reinforces the value of widening the scope of exoplanet surveys. By focusing more attention on faint stars often excluded from earlier studies, astronomers may uncover a previously underestimated population of large planets around small stars.

Atmospheric Science Opportunities

Beyond its unusual mass ratio, TOI-6894b is also of interest for atmospheric analysis. The planet’s equilibrium temperature is estimated at around 420 Kelvin (147°C), low by exoplanet standards. This cool environment may support methane-dominated chemistry, which is rare and challenging to detect.

Amaury Triaud, co-author and astrophysicist at the University of Birmingham, said in the Earth.com article: “Based on the stellar irradiation of TOI-6894b, we expect the atmosphere is dominated by methane chemistry, which is exceedingly rare to identify.” He added that it could serve as a valuable reference for studying atmospheric molecules such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

The planet is now a scheduled target for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is operated by NASA and partners including the European Space Agency (ESA). The JWST’s spectroscopic tools are expected to analyse the planet’s atmospheric layers in more detail, potentially detecting ammonia or other trace gases for the first time outside our Solar System. Details about the mission and its instrumentation are available through NASA’s JWST science portal.