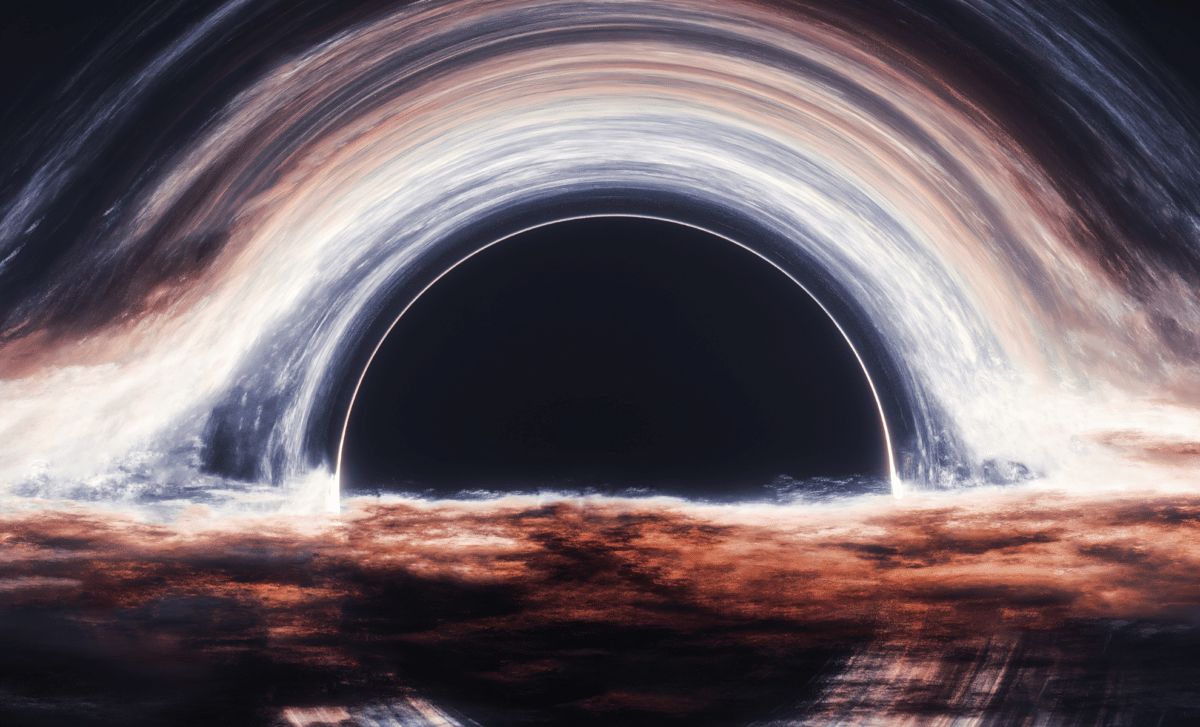

A recent study published on arXiv has revealed a black hole so massive and so ancient that it challenges long-standing models of how such cosmic giants form. Detected by Boyuan Liu and colleagues from the University of Cambridge using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), this black hole—located in galaxy Abell 2744-QSO1, weighs in at around 50 million times the mass of the Sun and appears to exist in a region nearly devoid of stars. This could mark one of the first viable candidates for a primordial black hole, a theoretical object dating back to the birth of the universe.

A Black Hole Without Stars: A Challenge to Standard Cosmology

The galaxy Abell 2744-QSO1, observed as it appeared just 13 billion years ago, presents a strange case. While harboring a massive black hole, the surrounding area lacks the expected stellar population that usually accompanies such a gravitational giant. This contradicts conventional models, where stars form first, eventually collapsing into black holes or feeding them over cosmic time.

“This is a puzzle, because the traditional theory says that you form stars first, or together with black holes,” says Liu.

The observation suggests something extraordinary: the black hole may have preceded star formation entirely, implying a radically different formation scenario than what current astrophysical models predict.

One potential explanation gaining traction is the primordial black hole hypothesis, first proposed by Stephen Hawking. These theoretical black holes would have formed directly from extreme density fluctuations moments after the Big Bang, bypassing the usual stellar lifecycle entirely.

This idea, long considered speculative, is now gaining renewed interest.

“With these new observations that normal [black hole formation] theories struggle to reproduce, the possibility of having massive primordial black holes in the early universe becomes more permissible,” Liu continues.

Such an object could have grown rapidly through mergers in the dense early universe, accumulating mass without relying on the collapse of stars.

Simulations Point To A Primordial Origin

The study, published on arXiv, incorporates advanced simulations to explore scenarios where massive black holes can exist in low-stellar-density environments so soon after the Big Bang. These simulations support the possibility that black holes formed from primordial density spikes rather than stellar processes.

One major obstacle has been reconciling the observed mass, 50 million solar masses, with primordial formation theories, which typically predict lower-mass black holes. Yet new models suggest that such black holes may not only have formed early but also merged quickly in a densely packed early universe.

“Here we are 50 times more massive,” Liu notes, emphasizing the scale difference compared to standard primordial predictions. “However, it is true that these primordial black holes are expected to be strongly clustered, and so it may well be that they managed to merge to quickly become much more massive.”

This clustering effect could create conditions ripe for rapid merging, leading to supermassive black holes like the one in Abell 2744-QSO1. If true, this would radically alter our understanding of how the first cosmic structures evolved, suggesting black holes played a foundational role in the formation of early galaxies, not the other way around.

The Implications For Black Hole Formation Models

The discovery has deep implications for our models of cosmic evolution. Current theories often begin with Population III stars, the first, metal-free stars, which collapse into black holes over millions of years. These black holes then grow by accretion and mergers, eventually forming the supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

Yet the object in Abell 2744-QSO1 appears too massive and too early to fit within that framework.

“It’s not decisive, but it’s an interesting and a kind of important possibility,” Liu says, referring to the primordial origin hypothesis. If black holes like this one can form independent of stars, it would overturn decades of astrophysical assumptions, requiring new theories to explain the formation of structure in the early universe.

Further observations with JWST and future telescopes will be crucial to confirming whether Abell 2744-QSO1 is indeed home to a primordial black hole, or if another exotic process is at play.

What This Could Mean For Cosmology

This candidate black hole reopens one of the most speculative yet tantalizing chapters in theoretical physics, the role of primordial black holes as dark matter. If they exist in sufficient numbers, they might even account for some or all of the missing mass in the universe.

Even if they don’t explain dark matter, their presence could reshape our timelines of structure formation, galaxy evolution, and the conditions of the early universe.

At the very least, Abell 2744-QSO1 represents a phenomenon that defies conventional logic, pushing the boundaries of what telescopes like JWST can uncover about the cosmos, and about its deepest, darkest mysteries.