Are quantum particles polygamous? New experiments suggest some of them abandon long-standing partnerships when conditions get crowded.

Quantum particles do not behave like isolated dots.

They interact, form bonds, and follow strict social rules. One of the most fundamental divides separates fermions and bosons.

Fermions refuse to share quantum states. Bosons happily pile together.

Those opposing traits underpin everything from solid matter to superconductors.

But new work shows that quantum relationships can break down in unexpected ways.

Researchers found that under extreme conditions, particles once thought to be strictly “monogamous” can suddenly change partners.

The result flips long-held assumptions about how particles move through materials.

When quantum norms fail

Electrons sometimes bind tightly to atoms, locking a material into an insulating state.

In other cases, they roam freely and carry electric current.

Under special conditions, electrons even pair with each other into Cooper pairs, enabling superconductivity.

Another important pairing involves electrons and holes.

A hole forms when an atom in a material loses an electron, leaving behind a mobile positive charge.

When an electron and hole bind, they create an exciton. Physicists often describe excitons as monogamous because breaking them apart requires energy.

Excitons behave like bosons. Individual electrons remain fermions.

That contrast makes them ideal for studying how fermions and bosons interact.

JQI Fellow Mohammad Hafezi and his colleagues wanted to see how changing the balance between these particles affects motion inside a material.

They predicted that packing a material with fermionic electrons would block excitons and slow them down.

The experiment produced the opposite result.

“We thought the experiment was done wrong,” says Daniel Suárez-Forero, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher who is now an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “That was the first reaction.”

The team built a carefully aligned layered material. Its structure forced electrons and excitons into a tidy grid of allowed positions. Electrons refused to share those sites. Excitons could hop between them.

At low electron densities, excitons behaved normally.

As more electrons entered the system, exciton motion slowed. Their paths became indirect as they navigated around occupied sites.

Then the system crossed a threshold.

When nearly every site filled with an electron, exciton mobility jumped sharply. Instead of freezing, excitons suddenly traveled farther than before.

“No one wanted to believe it,” says Pranshoo Upadhyay, a JQI graduate student and lead author of the paper.

‘It’s like, can you repeat it? And for about a month, we performed measurements on different locations of the sample with different excitation powers and replicated it in several other samples.”

The team repeated the experiment across samples, setups, and even continents. The effect persisted.

“We repeated the experiment in a different sample, in a different setup, and even in a different continent, and the result was exactly the same,” Suárez-Forero says.

Beyond exciton monogamy

Theory eventually caught up with experiment.

The researchers realized that excitons did not sit in the same way as free electrons and holes.

“At least this was what we thought,” said Tsung-Sheng Huang, a former JQI graduate student of the group who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Spain.

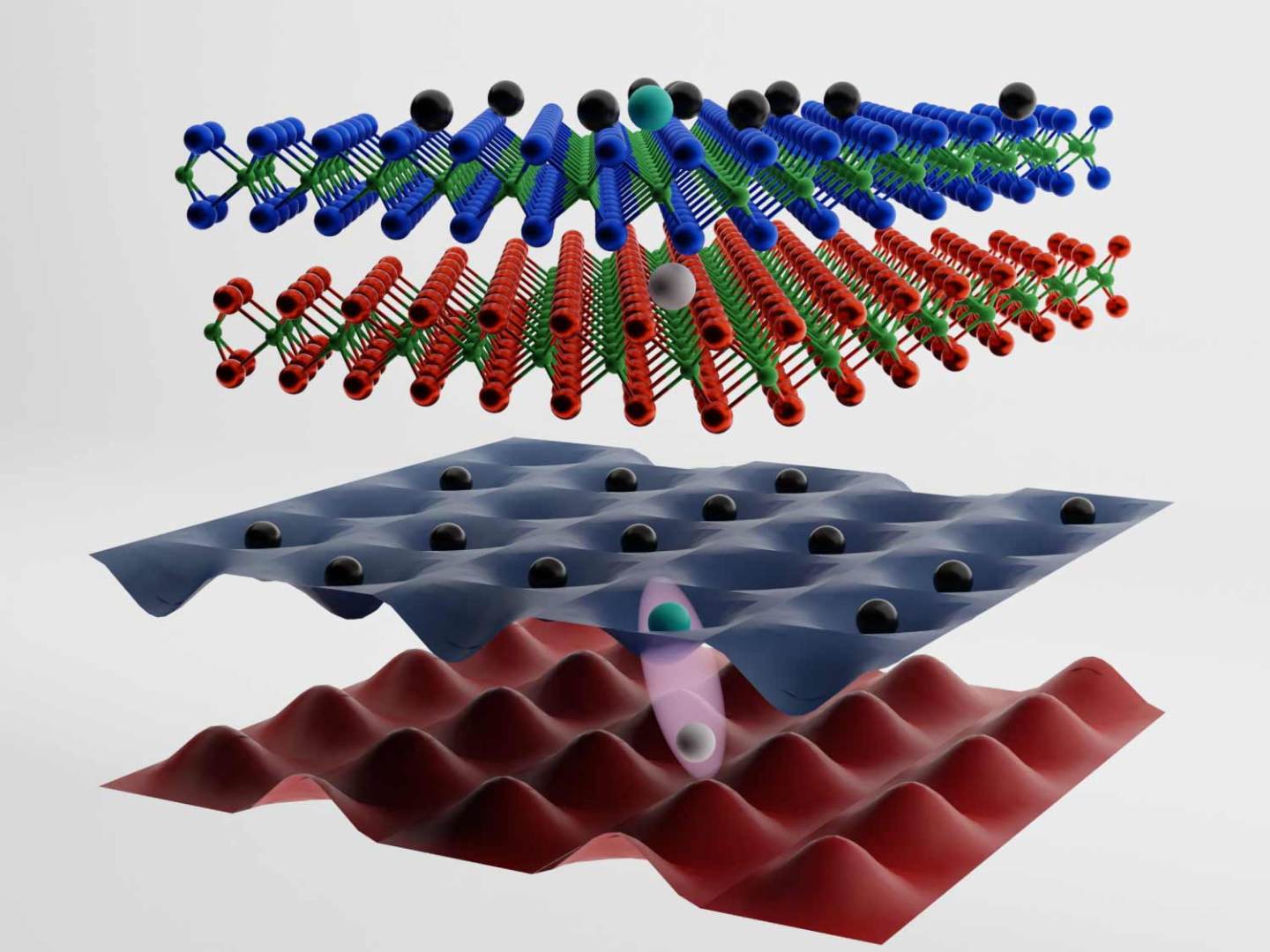

Layered material shows electrons and excitons moving through a quantum landscape. Credit – Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI

Layered material shows electrons and excitons moving through a quantum landscape. Credit – Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI

“Any external fermion should not see the constituents of the exciton separately; but in reality, the story is a little bit different.”

At very high electron densities, holes inside excitons began treating all nearby electrons as equivalent. The exclusive bond broke down.

Holes effectively switched partners repeatedly, a process the team calls non-monogamous hole diffusion.

That rapid partner-switching allowed excitons to move straight through the crowded system.

Instead of weaving around obstacles, they traveled efficiently before recombining and emitting light.

The researchers triggered the effect simply by adjusting the voltage.

That control makes the phenomenon attractive for future electronic and optical devices, including exciton-based solar technologies.

The study is published in the journal Science.