Anyone predicting in early 2000 that Athens would evolve into an important point on the international contemporary art map would almost certainly have received a skeptical look. Greece didn’t have a fully operational Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) at the turn of the century, nor a biennale, nor even a consistent presence of artists at major shows in different parts of the world. The country’s attention was on one thing: the 2004 Olympic Games. This meant that the husks of abandoned industrial facilities needed to be swiftly turned into new infrastructure in a Balkan-Mediterranean capital that, though beleaguered, was fast connecting with the rest of the planet.

In 2003, the painting “Asperges Me” (Dry Skin) by Belgian artist Thierry de Cordier, shown at the “Outlook” exhibition, caused a minor cultural earthquake in Athens. The image of a penis in dialogue with a crucifix was not treated as an invitation to reflection, but as a threat to the moral order. The piece was taken down and the curator was dragged through the courts for putting up such an “obscene and disgraceful painting,” viewed as the “creation of a perverted artistic mind.” A series of reports in the international media noted that, rather than celebrating a success on the global art scene, Athens was projecting intolerance and fanaticism. Indeed, the first international contemporary art exhibition held in Greece as part of the Cultural Olympiad was marked by more than the “scandal” surrounding “Asperges Me.” There were incidents of vandalism involving other works which – presented outside conventional gallery spaces, in former industrial buildings and abandoned sites in Gazi – sparked heated debates about the relationship between the city, modern life, and art. And that was just the beginning.

‘Outlook,’ a part of which was held at the Benaki’s Pireos annex, was part of the Cultural Olympiad and a pioneering event.

‘Outlook,’ a part of which was held at the Benaki’s Pireos annex, was part of the Cultural Olympiad and a pioneering event.

All told, it took the first two decades of the 21st century for Athens to acquire something resembling an art scene through its public institution

Despite these incidents, the groundwork for a flourishing contemporary art scene had already been laid by the turn of the new millennium. This process began quietly but decisively with education. The Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA), through accomplished visual artists who were also generous and committed teachers, played a key role in preparing the ground for later successes, shaping outward-looking, open-minded artists, many of whom began to make an international name for themselves.

Moreover, a number of the school’s graduates became art teachers at schools, before the subject practically disappeared from school curriculums. It is to this cultivation of a visual culture through the educational system that we owe today’s boom in gallery exhibitions, artistic collaborations and platforms – and, above all, a generation of art lovers in their 30s and 40s who fill the halls of museums and galleries.

The ‘homeless’ museum

The path was far from easy. The aspiration to endow Athens with a functional museum of contemporary art became a test of endurance. The National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (EMST) was founded in 2000, but had no permanent home. Repeated delays, administrative deadlocks, changes in leadership and the partial or intermittent use of the Fix brewery building for roughly 15 years repeatedly called the institution’s very viability into question.

The National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum, by contrast – older and more institutionally sound – followed a parallel path. Planning for its major expansion began in 2008, with construction starting in 2014, keeping the museum closed for long stretches. The project was completed in 2021, doubling the available space, but not without cost: a prolonged absence from the public eye and an intense debate over the role and identity of the “new” National Gallery.

The extension of the National Gallery doubled its exhibition spaces, but also sparked a debate about its role and character.

The extension of the National Gallery doubled its exhibition spaces, but also sparked a debate about its role and character.

All told, it took the first two decades of the 21st century for Athens to acquire something resembling an art scene through its public institution. In February 2020, the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (EMST) finally opened to the public in full operation, while the reopening of the National Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum coincided with the 200th anniversary of the 1821 Greek War of Independence. In the years that followed, both institutions were tested by the financial crisis and the pandemic, as were private museums and galleries.

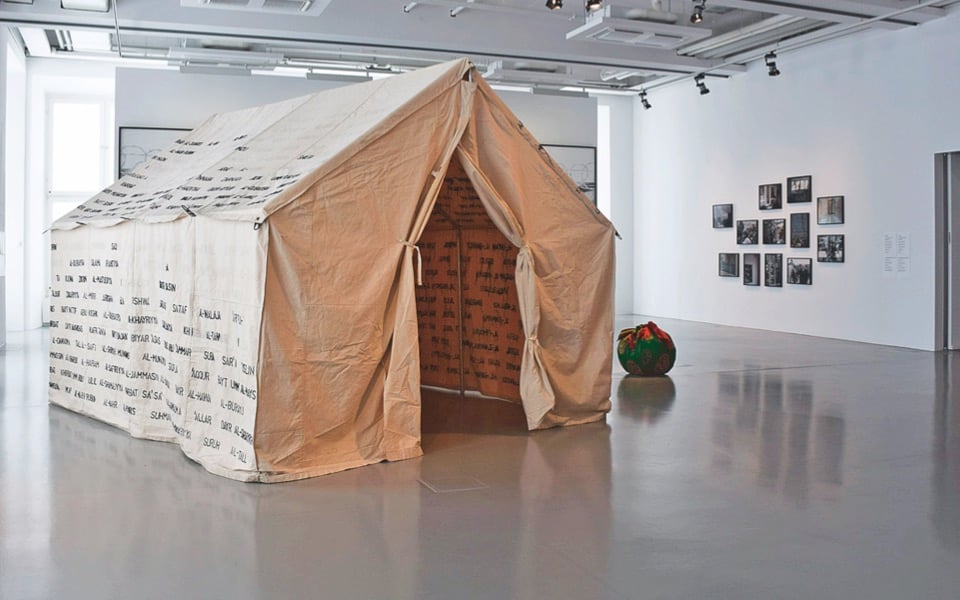

Meanwhile, the already well-fertilized cultural ground was bearing fruit. The first Athens Biennale, titled “Destroy Athens,” was held in 2007 at the Technopolis municipal cultural center, and more followed. Documenta 14 (2017), split between the exhibition capital of contemporary avant-garde art, Kassel, and Athens, turned the city into a site of political, social and historical inquiry, focused on the Greek crisis, economic debt, democracy and colonialism.

At the same time, the dynamic presence of cultural organizations such as NEON and institutions like DESTE, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and the Onassis Cultural Center – Stegi played a decisive role by hosting international-caliber art exhibitions. After a long and eventful journey, the Basil and Elise Goulandris Museum also opened its doors in 2019, bringing a major collection of modern and contemporary art to the central neighborhood of Pangrati. Together with the renovation and reactivation of the Athens Conservatoire, the axis stretching from Vassileos Konstantinou Avenue along Syngrou Avenue to the seafront has effectively become an art route.

One of Edgar Degas’ famous dancer statues is included in the wonderful collection of modern art on show at the Goulandris Museum. [InTime News]

One of Edgar Degas’ famous dancer statues is included in the wonderful collection of modern art on show at the Goulandris Museum. [InTime News]

Add to this the Museum of Cycladic Art’s contemporary turn and Athens now regularly presents the work of major, internationally renowned artists that were once out of the average Greek’s reach.

Thanks to private initiatives, moreover, Greek art has also strengthened its international presence. There are now regular participations in biennales, collaborations with major international museums and works that travel abroad.

Private collections

Another important part in cultivating a broader artistic culture was played by Greek collectors who chose to share their acquisitions with the public. One of the most recent of such major initiatives was the donation in 2022 of 350 artworks from the Dimitris Daskalopoulos Collection to four institutions: Athens’ EMST, the Tate in London, the Guggenheim in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago.

The expansion of art galleries in Athens was not the result of some plan but unfolded gradually. In the early years of the 21st century, most galleries were clustered in and around Kolonaki. Yet the city extended far beyond the scene in which art was being presented. Galleries began moving into new neighborhoods – formerly neglected areas such as Kerameikos, as well as districts further east or north.

This dispersal signaled economic vitality and engagement with more diverse audiences. Reports from the Hellenic Statistical Authority do not point to an explosion, but to stability: The number of exhibitions fluctuates only slightly. What has changed is their density, and geography.

The first Athens Biennale, dedicated to the theme ‘Destroy Athens,’ was held in 2007 at the municipality’s Technopolis cultural center in Gazi.

The first Athens Biennale, dedicated to the theme ‘Destroy Athens,’ was held in 2007 at the municipality’s Technopolis cultural center in Gazi.

The simultaneous closure of historic art spaces such as Nees Morfes and Desmos marked the end of a cycle in the promotion of Greek art that had shaped the previous century. However, it also contributed to the development of the Institute of Contemporary Greek Art (ISET), a nonprofit organization founded in 2009 with the aim of preserving, recording and documenting contemporary Greek art from 1945 to the present.

In 2021, ISET’s archive and facilities were donated to the National Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum, under whose auspices the institute now operates. Long-standing guardians of the history of modern Greek art also include the Benaki Museum and the Basil and Marina Theocharakis Foundation, founded in 2004.

The realization that the lack of memory is a bigger threat to contemporary Greek art than the lack of work has mobilized both the National Gallery – Alexandros Soutzos Museum and the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens. Under the leadership of Syrago Tsiara at the National Gallery and Katerina Gregos at EMST, both public museums have incorporated archival exhibitions into their annual programming.

Through these initiatives – and more broadly – we have also seen a determined effort to correct the narrative of art history by showcasing – not on entirely equal terms – women artists who have produced, and continue to produce, work of an exceptional caliber.

The Documenta 14 exhibitions turned Athens into an international platform for political, social and historical inquiry through the visual arts.

The Documenta 14 exhibitions turned Athens into an international platform for political, social and historical inquiry through the visual arts.