Warning: This story contains content that may be distressing.

Sammie Corbett started self-harming when she was only nine years old.

She is now 24 and has lost count of the number of times she has attempted to take her own life.

“I don’t know the exact number, but well over 20 attempts, well over,” Sammie said.

If you or someone you know needs help:

“I had my first at 20 [years old] and that’s when my family knew what was going on because no one knew before that.”

Sammie was diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety after that first suicide attempt.

That attempt also marked the start of what has been a long and relentless journey to appropriate care and support.

“That’s when I went to my first psych ward … it was awful, the nurses treated you like you weren’t human,” Sammie said.

“They didn’t have any therapy or anything.

“You just stayed there for a week, no access to anything and nurses walking in on you when you’re on the toilet.”

Patient says emergency departments ‘don’t care’

Sammie Corbett has developed post-traumatic stress disorder because of her treatment at hospital. (ABC News: Rosie King)

In the past four years, Sammie has spent time in six mental health units both in Canberra and surrounding regional New South Wales towns, describing every experience as “re-traumatising”.

“As soon as they’ve dealt with whatever is going on physically, you wait and wait, rotting in anxiety, to see someone from the mental health team,” she said.

“Then they don’t take you seriously, they don’t care, they knock you down.

“I’ve had a few of them tell me that I’m 24 and need to stop doing this, and another one asked if I was just doing it for attention.

“Or I’m told it’s not a big deal and I’ll get over it in a few days.”

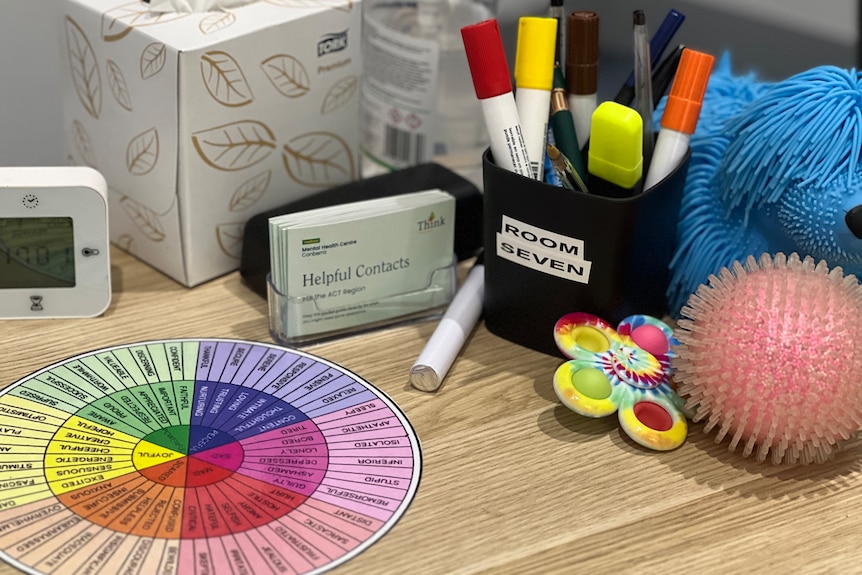

Some mental health programs in the ACT are not available to residents in NSW border towns. (ABC News: Rosie King)

Sammie said she had developed post-traumatic stress disorder because of her treatment at hospital.

“I don’t even try to get help anymore because it’s so traumatising that I don’t want to go through that,” she said.

“The thought of doing anything that could land me there, that’s probably the one thing that’s stopping me, being so scared of having to go to hospital.”

Access to out-patient clinics restricted

Having a New South Wales address adds another layer of complexity to Sammie’s ability to access treatment.

Sammie and her family call Royalla, a New South Wales town just south of the ACT border, home.

But some out-patient services in the ACT recommended upon discharge, are restricted to Canberra residents only.

Among them is the Step Up Step Down Program, which is a residential mental health program for people recovering from an acute mental health episode.

“They try to set you up when you’re leaving for out-patient clinics,” Sammie said.

“Because I’m not an ACT resident, a lot of them I didn’t qualify for, so I didn’t have a lot of options.

“We’re five minutes away from the ACT and yet there are so many options that wouldn’t take me — or couldn’t.”

Mother says system has ‘heartbreaking’ consequences

Sammie’s mother says border residents should not be excluded from vital ACT services. (ABC News: Rosie King)

For Sammie’s mum, Rochelle Corbett, watching the system fail her daughter time and time again has been both a heartbreaking and enraging experience.

“It’s absolutely heartbreaking,” Ms Corbett said.

“Sammie has just been so vulnerable and the people we thought could help her have been dismissive and disrespectful.

“There’s just no compassion shown to her and no grace for the situation she’s in — it’s been really, really difficult.”

Ms Corbett also said the fact that NSW border residents were being excluded from ACT services that could drastically help them recover needed to be addressed urgently.

“The stock standard response has been, ‘Just take Sammie to emergency when things get really bad’, which is not good enough,” Ms Corbett said.

“There must be some solution that can be implemented with the patient’s best interests at heart rather than red tape and policies.”

Units prioritise safety over comfort, official says

Canberra Health Service’s general manager for Mental Health Bruno Aloisi admitted emergency departments were not an ideal environment for patients in acute psychological distress.

“But when someone needs to access urgent care, it’s the environment that can provide that care quickly,”

Mr Aloisi said.

Bruno Aloisi says he regrets any instance where a patient isn’t treated with dignity. (ABC News: Matt Roberts)

Mr Aloisi also accepted the criticism that adult mental health units in the ACT were not homely or geared towards ensuring a patient’s long-term recovery.

Rather, he said their goal was to keep those staying there safe.

“Those environments are designed specifically around safety so that has to be considered,” he said.

“While we would like them to be more home-like, unfortunately, because of those considerations around safety, you can’t have it both ways.

“We could always absolutely make improvements, but they are designed with a specific purpose in mind, particularly at that acute end.”

Mr Aloisi also added that trauma-informed training was provided to all public health staff and said he was confident every employee was committed to providing “empathic, caring” treatment.

He said he regretted any instance when a patient was not treated with dignity, care or respect, adding that “would not be his expectation”.

Advocates call for redesign of emergency crisis care

The ACT’s Mental Health Community Coalition, the peak body representing the community-managed mental health sector, has long called for emergency departments to be redesigned with an improved focus on human rights.

Lisa Kelly says more funding is required for early intervention and prevention. (ABC News: Mark Moore)

“Emergency departments are not well-designed to manage people in mental health crisis,” chief executive Lisa Kelly said.

“That often requires somebody to take time and build rapport and connection and that’s not often what emergency departments are well-equipped to do.”

Ms Kelly also added that there was room for improvement when it came to the care and support provided in mental health units.

But she argued that too often the focus was on fixing services at the acute end of the mental health spectrum rather than on preventing people from reaching that point.

“It’s really sad because it means we have a service system that is waiting for people to get really unwell before they can get the help they need,”

Ms Kelly said.

“What we know is that when people get the help at the time they ask for it, we can make a significant impact and change the trajectory of their mental health condition.

“And taking that pressure then off the acute mental health units would allow them to deliver models of care that are more compassionate and empathetically driven.”

Ms Kelly said more ACT government funding was vital and it needed to be split in two — used to increase the capacity of existing services but also to fund new ones, such as social groups for people with anxiety and at-home care to support people to stay out of hospital.

She said that approach would address the long waiting lists Canberrans are coming up against when seeking help, while also filling some of the gaps that exist in the sector.

The ACT Health Directorate has set aside $184 million across all services for this financial year. (ABC News: Rosie King)

ACT health spending reaches record levels

On any given day in the ACT, around 8,000 Canberrans are struggling to access the mental health support they need.

The ACT government is spending more on the mental health sector than ever before.

Data provided to the ABC by the Health Directorate shows $178 million was allocated across all services last financial year, with 43 per cent spent on acute care and 32 per cent spent on supporting community mental health services.

This financial year, spending will jump to $184 million, with the same portion allocated to acute care and an increase to 35 per cent for community mental health services.

For Sammie, it is a federal government-funded service that has finally come to her rescue — Medicare Mental Health, which operates in Civic and Tuggeranong.

They are walk-in centres where people are offered help to navigate the mental health system and connect with appropriate services.

“If we can’t find the right service in the community, then we actually bring them in and provide services internally here,” clinical psychologist Vanessa Hamilton said.

Medicare Mental Health is free and open to anyone — a referral or diagnosis is not needed — and the centres are staffed by a raft of mental health professionals, including nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists and peer workers.

Critically, it currently has no wait list.

Vanessa Hamilton says Medicare Mental Health should not fill the gaps in the ACT’s system. (ABC News: Joel Wilson)

But Ms Hamilton warns against seeing Medicare Mental Health as the answer to all the shortfalls of the mental health sector in the ACT.

“It’s hard because even though it’s a really important service and it meets a clear need, it’s still a short to medium service, so there is always going to be an end point,” she said.

“People come in, they have a period of intervention and then they leave our service.

“We know that best practice is multi-year, quite long-term intervention and that’s not funded in any way, shape or form, so there’s absolutely a gap there.”

For now, though, Sammie feels it is exactly where she needs to be.

“They actually give you therapy and it’s amazing,”

she said.

“I’m doing individual and group therapy every week and I can also access phone counselling if I feel like I need it.

“I’m finally learning coping skills, I have something to look forward to every week, and it’s nice, very nice.”