Become a paid member to listen to this article

Every month, Untapped New York will release a new essay from Jo Holmes about the life and work of the late architect Richard Roth, Jr. of Emery Roth & Sons. Each essay explores a different building or developer from Richard’s career, intertwined with stories of his personal life and snippets of exclusive interviews conducted by Holmes and Untapped New York’s Justin Rivers (which can be viewed in our on-demand video archive). Check out the whole series here!

A Flagship Store

Richard Roth Jr. was undoubtedly a people person. While he was proud of the work he did, he was also delighted by the relationships forged throughout his life. One such friendship grew from his involvement with Alexander’s department stores, specifically the flagship building in Manhattan. It was through that project that he met Op artist Stefan Knapp, who would become a lifelong family friend. In fact, many of Richard’s closest friends were artists. He found commissioning artworks for the lobbies and plazas of the buildings to be among the most gratifying parts of the job.

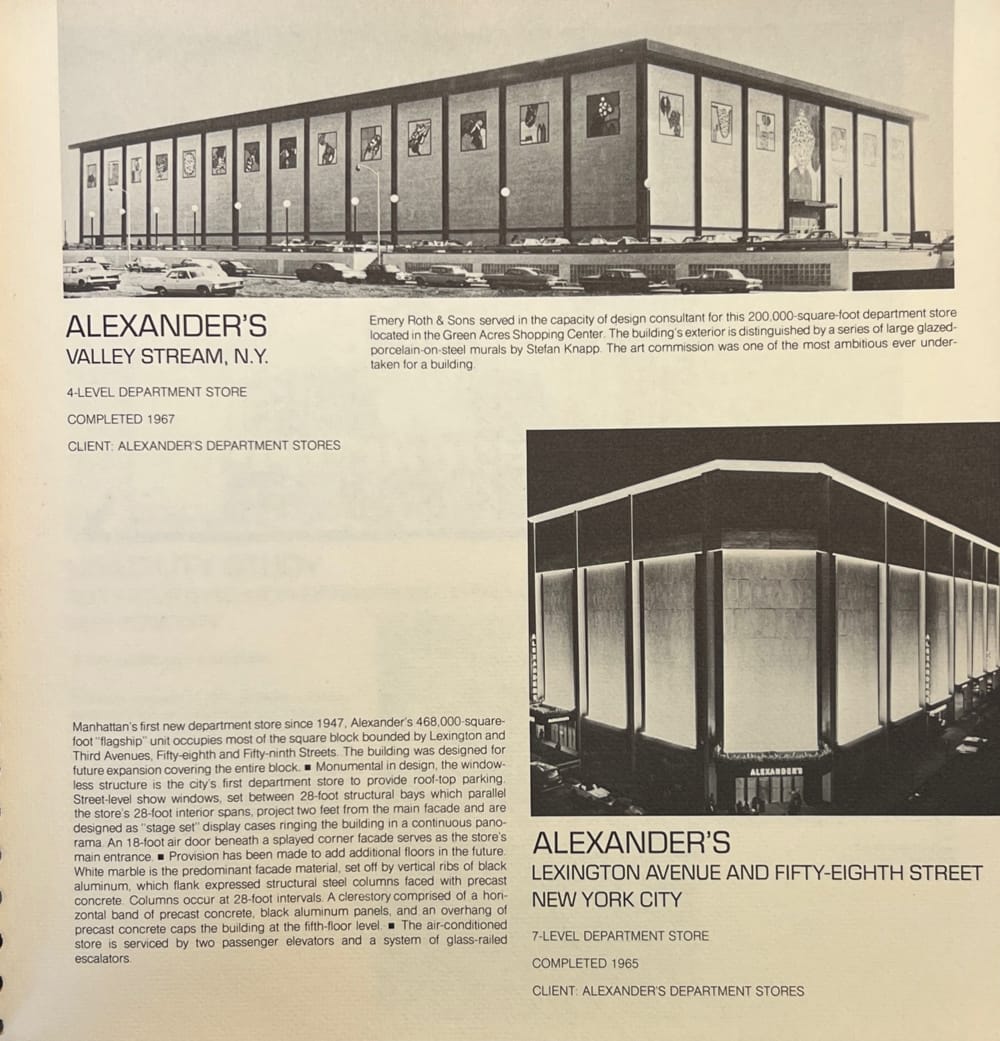

In 1963, Emery Roth & Sons ran a competition to design a building for popular retailer Alexander’s in Midtown Manhattan. It would become the flagship store. Until then, the main store had been in the Bronx, with an additional ‘out of town’ location in New Jersey. Subsequently, Richard designed Alexander’s stores in Valley Stream (1967) and Kings Plaza (1968), as well as the branch housed in the Mall at the World Trade Center (1974).

Image from the Roth Family Archives

Image from the Roth Family Archives

The winning design for the Midtown site at 731 Lexington Avenue (on the corner of 58th Street) and incorporated a piece of artwork on the façade. Sandy Farkas, son of Alexander’s founder, George Farkas, wanted to use designs by Salvador Dali.

“Dali had done 17 murals which he’d sold at a sort of bargain basement price to Sandy,” Richard said. “Sandy wanted to transpose those murals onto the side of the building—he wanted to turn them into mosaics as he’d seen in Florence.” Richard was concerned by how long that process would take, given the sheer size of the murals. “It seemed Dali didn’t want to do it either,” Richard explained.

An Awkward Encounter

Sandy decided to ask another artist, Stefan Knapp, to recreate the Dali murals. Knapp was a Polish-born painter and sculptor who developed and patented a technique of painting with enamel paint on steel. He created a series of murals for London’s Heathrow Airport in 1959 (‘Murals 1959’) and for the New Jersey Alexander’s store. Unsurprisingly, Knapp was not thrilled to be asked to replicate another artist’s work—even Dalí’s.

“I walked into a meeting with Farkas at Alexander’s head office at 500 7th Avenue and found Dali there. Knapp, whom I had really just met the week before, was sitting outside. It was pretty awkward,” Richard remembered. “In the end, nobody did it—and the Farkas family sold the Dali pieces for a fortune!”

Instead, Alexander’s commissioned an original work by Knapp. The piece was composed of more thant 400 large white panels with rows of colorfully enamelled steel domes. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New Yorker that “the whole thing looked like a billboard filled with eyeballs or hubcaps or salad bowls. It was easily the most monumental piece of Op Art in New York.”

Op Art, or Optical Art is an abstract style that became popular in the 1960s. It is characterized by geometric shapes and high contrast colors that often create optical illusions that warp the viewer’s perception. In addition to Knapp, other artists working in this mode included Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, and Yaacov Agam.

A panel from Knapp’s mural on display at the Museum of the City of New York, Photo Courtesy of Robyn Roth-Moise

A panel from Knapp’s mural on display at the Museum of the City of New York, Photo Courtesy of Robyn Roth-Moise

Alexander’s Manhattan store opened in 1965, shortly before the company went public in 1968. Since founder George Farkas always purchased the land and property for his stores rather than leasing the storefronts, creating a valuable real estate portfolio. Interstate Properties took over the stores in 1980 to maximize the value of the company’s real estate.

Steven Roth (no relation to Richard) was at the helm of Interstate at the time and would later become the largest commercial landlord in New York City at the helm of Vornado Realty Trust. Donald Trump even held a significant stake for several years, but, having used it as collateral, was forced to hand it over to settle a loan in 1991.

The flagship store, along with all other Alexander’s locations, shut down in 1992 when the company was forced into bankruptcy. While the stores have disappeared, some of the artwork survives.

A New Lease of Life

One of the Stefan Knapp panels from the Manhattan store is at the Museum of the City of New York. According to Paul Goldberger, writing in The New Yorker in November 2000, Manhattanite art collector Barbara Jakobsen acquired 80 of the domes from art dealer Mark Macdonald and reconstructed a panel in her garden. Macdonald got hold of the domes from the demolition contractor. The panels on display at MCNY were donated by Jakobsen and unveiled in 2023.

A few panels from a vast mural that once graced the New Jersey Alexander’s store have been restored and installed at the new Valley Hospital in Paramus. More of Knapp’s work can found in the collections of museums around the world, including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and the Tate Gallery in London.

The author Jo Holmes (left) and Richard’s daughter, Robyn Roth-Moise (right), posing with Knapp’s work at the Museum of the City of New York

The author Jo Holmes (left) and Richard’s daughter, Robyn Roth-Moise (right), posing with Knapp’s work at the Museum of the City of New York

Over the course of the Alexander’s project, Knapp became a great friend of the Roth family. Richard was fascinated by Knapp’s life experiences. As a teenager, he had spent time in a Siberian gulag. Released in 1942, he ended up in the United Kingdom and joined the Royal Air Force, serving as an officer and Spitfire pilot. After the war, he stayed in London and studied at the Royal Academy and the Slade School of Fine Art.

“We were as close as two people could be,” said Richard. Knapp even lived in the Roth’s apartment for a time. Richard was Godfather to Knapp’s son Robin. Richard and his wife, Alene, spent many summers with Stefan and his wife, Cathy, when the Knapps had an apartment in Le Lavandou in the South of France.

Richard recalled a scary incident where Knapp had a life-threatening tooth infection. Richard remembered seeing a body bag in the hospital room. Thankfully, Knapp made a full recovery after a surgery performed by the head of dental surgery at Lenox Hill. (Shockingly, the surgeon himself was killed in a flying accident just a few hours after the operation.)

An Artistic Temperament

Perhaps given his own artistic abilities, it’s no surprise Richard had many friends in the art world. “My friends were not so much in the architecture field. I had more friends who were artists…You know, we had a lot in common. We could talk. And I enjoyed their company.”

Occasionally, he would work in exchange for pieces of art. “One of my closest friends was Richard Anuszkiewicz, and he asked me to design his studio in New Jersey in exchange for a painting. I said yes, why not?”

Anuszkievic was an American painter, printmaker, and sculptor of Polish descent, one of the founders of Op Art. Life magazine described him as ‘one of the new wizards of Op’ in 1964. He exhibited at the Venice Biennale, Florence Biennale, and Documenta. His works are in permanent collections around the world.

“I was out there supervising it one weekend, and I noticed that people were digging underneath the foundation.” The studio was built on a hill behind the house. “I asked Anuszkievic what they were doing. He said, ‘My father’s doing that—he’s creating a basement.’ I said, ‘It’s gonna fall over!'” Anuszkiewicz’s father—then in his late eighties—was trying to create more space. “Luckily, I got up there before the whole thing just toppled down the hill!”

“I also designed the Fischbach Gallery on 57th Street in exchange for a painting,” Richard said. The Fishbachs were the largest electrical contractors in New York City at the time, and Richard had actually designed an extension for their house in Westchester. “And I designed an apartment for Harry Fischbach, the father, in exchange for getting electric work done in my apartment!”

Richard was good friends with gallerist Denise René. “She ran one of the leading modern art galleries in Paris. She represented all the optical art painters.” René was opening a gallery in New York, and Richard acted as an unpaid consultant. In return, Denise gave Richard and his family a number of items, including some small steel sculptures by Hungarian ‘cybernetic’ artist Nicolas Schöffer. A while later, Schöffer himself came to a gathering of artists at Richard’s New York apartment, where one of his pieces was on display on a coffee table. “All of a sudden, he turned it round. Apparently, we’d always had it back to front!” laughed Richard.

Another friend was the sculptor Art Brenner, who lived in France for a good many years. “Part of the fun of going to Paris was to see Art. He ended up living on a barge there. His original studio and apartment at 17 Rue d’Aboukir was around the corner from Les Halles, and it was wonderful,” described Richard. He was thrilled to have experienced the famous market before it was demolished in 1973.

In 1974, Richard commissioned Art to create a large sculpture to sit outside a hotel near the Philadelphia airport. Unfortunately, Richard’s clients had altered his designs for the hotel. “They decided to cheapen the façade,” said Richard. “So, I said, ‘Art, I want you to make something as big as possible because they’ve screwed up the building and I wanna hide the building as much as possible.’ So, he did this huge thing about 30 feet by about 20 feet in height. And it was orange, so your eyes go right to it.” The sculpture, which Brenner called ‘Atlas X,’ has since been moved to another nearby hotel’s parking lot and painted blue—likely to coordinate with the Hilton branding. Richard had a small maquette of the sculpture.

Atlas X by Art Brenner, Photo by Robert MorbeckA Lifelong Passion

Atlas X by Art Brenner, Photo by Robert MorbeckA Lifelong Passion

As someone who had contemplated a career as an artist, Richard instinctively took a keen interest in any artwork planned for his buildings. One of the reasons he enjoyed working with maverick developer Melvyn Kaufmann was Kaufmann’s passion for incorporating ‘decorative’ features. For 77 Water Street, they worked with lighting designer Howard Brandston, graphic designer Rudy de Harak, and sculptor Pamela Waters.

Richard was especially excited by the installations at The Pan Am building, including the sculpture ‘Flight’ by Richard Lippold and a large mural by Josef Albers. He loved the ‘dandelion’ fountains he’d commissioned for the plaza at 1345 Avenue of the Americas, formerly Burlington House. “They really were beautiful and, when it was hot, and the wind would blow, people would sit to the lee of them so the water would spray on them.”