Twenty years ago, my history of how racism shaped Dallas, White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001, was published. I ended the book on a pessimistic note.

“By the mid-to-late 1990s, Dallas represented a dispirited collage of mutually antagonistic fragments, a sum much less than its alienated parts,” I wrote. “If Dallas never exploded [in riots] like Watts, Birmingham or Detroit, it was not because it enjoyed a more dynamic leadership than those cities, but because of a self-induced paralysis that left the structures of oppression soundly intact.”

Dallas today in some ways is not as relentlessly dysfunctional as it was when I wrote those words. Coalitions have formed briefly to make the city a better place. But these alliances have proved fleeting. Genuine racial and economic justice remains unrealized.

I wrote that the city’s self-image rested on suppression of its violent, white supremacist history. To make it more attractive to outside investment, leaders turned Dallas into a “laboratory of forgetfulness.”

Opinion

Politicians erased a past deformed by slavery, Reconstruction-era racial terrorism, lynchings and bombings of Black neighborhoods, Ku Klux Klan dominance in the 1920s, police violence and selective criminal prosecution of Black and brown residents. In the place of honest history, the public was fed a myth about a city guided by wise, selfless business elites who based all their decisions on what was good for “the city as a whole.”

Since White Metropolis was published, activists have forced the community to honestly face its bloody record.

On August 19, 2017, at least 2,300 rallied in front of Dallas City Hall to call for the removal of landmarks honoring Confederate enslavers and traitors. Statues came down and schools named after Confederates were rededicated.

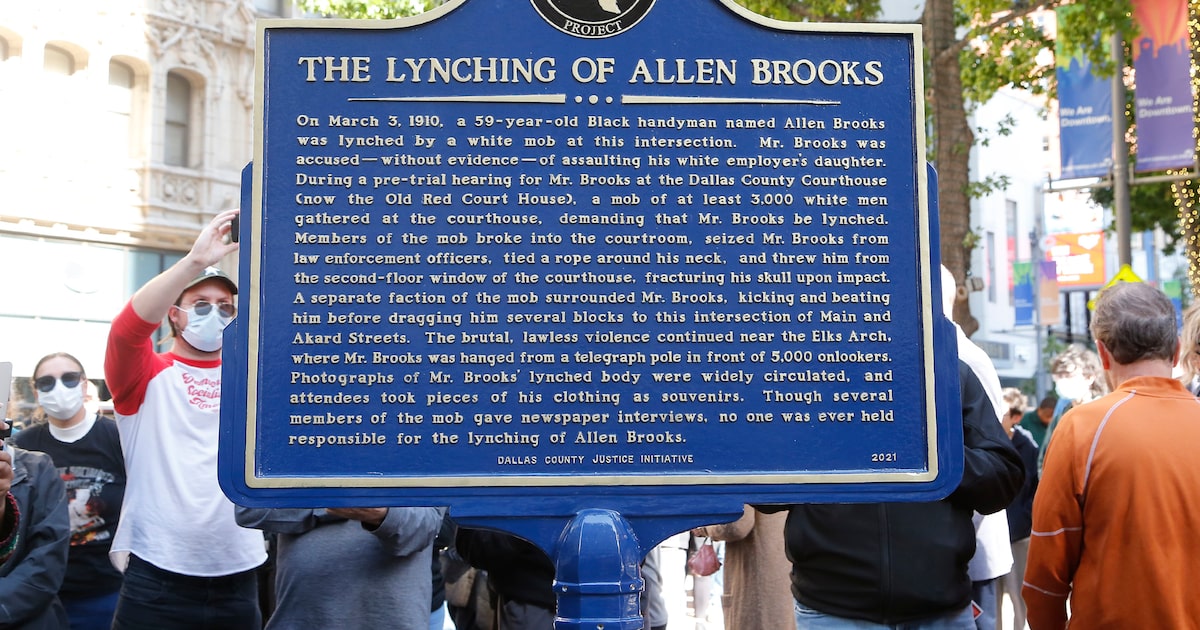

The Dallas County Justice Initiative and Remembering Black Dallas erected markers memorializing lynchings and placed plaques noting ways African Americans have shaped the city’s history. A statue now honors Santos Rodriguez, a Latino teenager murdered by a Dallas police officer in 1973.

Thousands marched through Dallas to support immigrants in 2006. A similar march drew thousands more in 2025. It’s hard to imagine such mass mobilizations in the city I described in White Metropolis.

Yet White and Asian people in Dallas are still two to three times more likely to earn a living wage than Black and brown people. More than 36% of Dallas residents live in food deserts where finding affordable, healthy food is a hardship. And those who live in food deserts are disproportionately Black and brown.

Dallas took nearly four years to remove a mound of toxic construction waste in the Floral Farms neighborhood reaching 60 feet in height that became infamous as “Shingle Mountain,” and another two years to pass an ordinance rendering such an environmental catastrophe less likely in the future.

Like 20 years ago, Dallas is still a place where, if you are Black or brown, you are far more likely to be poor, hungry and exposed to deadly pollutants. If this is not to be true 20 years from now, city activists will have to build enduring alliances.

Dallas history teaches us that justice will only come through struggle from the bottom up.

Michael Phillips is an author and historian.