China’s upcoming Chang’e-7 mission is poised to reshape the geopolitical and scientific landscape of lunar exploration. This highly ambitious operation will target the Moon’s south pole, deploying a suite of robotic instruments to investigate water ice, a critical resource for future deep-space missions. The mission represents not just a scientific inquiry but a strategic leap in China’s broader space roadmap, one that underscores its long-term ambitions to establish a permanent foothold on the Moon.

A New Phase In China’s Lunar Strategy

The Chang’e-7 mission is a central component of China’s “Phase Four” in its carefully sequenced lunar exploration program, which has steadily advanced over the past two decades. This methodical approach has seen the deployment of orbiters, landers, rovers, and sample return missions, demonstrating a clear trajectory from exploration to sustained lunar operations.

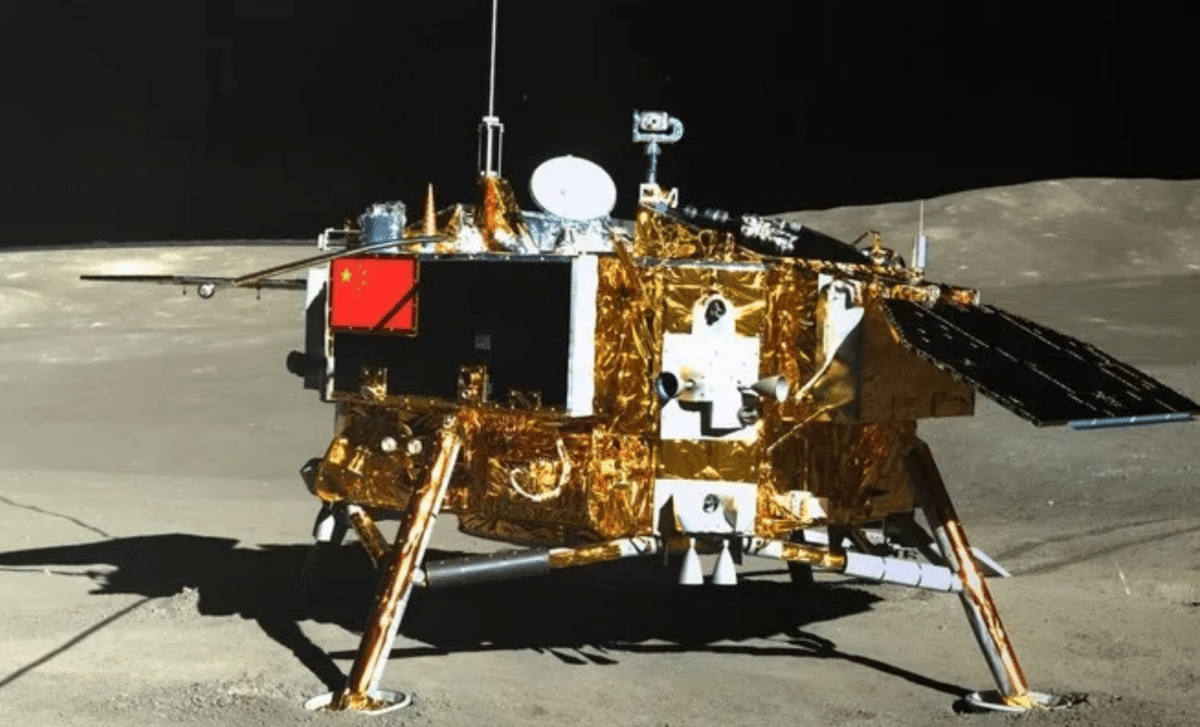

Unlike previous missions, Chang’e-7 will send not just a lander, but a full mission architecture: an orbiter, a rover, a small hopping probe, and a relay satellite designed to maintain communication with Earth from the Moon’s far side. This configuration enables it to explore the permanently shadowed regions of the lunar south pole, areas of immense scientific interest due to their potential to harbor ancient water ice deposits. These regions, shielded from sunlight for billions of years, may hold pristine records of the solar system’s volatile delivery history, and represent one of the best hopes for finding usable water beyond Earth.

Science Meets Strategy At The Lunar South Pole

While the stated goal of Chang’e-7 is scientific investigation, the mission’s design and objectives make it clear that China is preparing for much more than a research campaign. As detailed by Space Explored, this mission enables precision landing near hazardous terrain, long-duration autonomous surface operations, and crucially, resource prospecting. These are not just exploratory capabilities, they are the technical foundations for lunar habitation.

The focus on the Moon’s south pole is not incidental. This area offers both continuous sunlight on certain ridgelines, ideal for solar power, and deep craters where water ice may persist. This dual utility makes it prime territory for permanent infrastructure. As NASA’s Artemis program also targets this region, the lunar south pole is fast becoming the center of a new space race, one focused not on first steps, but on long-term presence and resource control.

Chang’e-7’s Hopping Probe: A Game-Changer For Shadowed Terrain

One of the most intriguing components of the Chang’e-7 suite is its hopping probe, engineered to traverse where traditional wheeled rovers cannot. Permanently shadowed craters, where the Sun never rises, pose insurmountable challenges for most lunar vehicles. But the hopping probe could offer the first in-situ data from deep within these dark zones.

This innovation is not just technologically impressive; it could provide critical insights into whether these regions contain harvestable water ice. If successful, Chang’e-7 will establish a technological precedent for terrain-agnostic exploration, a necessity for tapping into the Moon’s most valuable hidden reserves. It also sends a strong signal: China is investing in mobility platforms that prioritize resource extraction, aligning closely with its long-term lunar construction goals.

A Stepping Stone To Lunar Infrastructure

The Chang’e-7 mission is a precursor to Chang’e-8, which will test in-situ resource utilization and potentially begin trials for 3D-printing construction techniques using lunar soil. The ultimate aim: a jointly operated International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which China hopes to develop with international partners. These missions fit into a coherent roadmap that goes far beyond exploratory sorties, they are part of a blueprint for permanent lunar infrastructure.

China has not been alone in this vision. Russia, India, Japan, and members of the European Space Agency are also accelerating their lunar ambitions, adding layers of complexity to the emerging multi-polar lunar order. The difference lies in execution pace: while others plan, China is already building. With Chang’e-7, it’s not just making another Moon landing, it’s laying the foundations for a new space economy.

Space Exploration Enters A New Era

As Space Explored highlights, the Moon is no longer just a symbol of prestige or technological prowess. The current wave of exploration, epitomized by missions like Chang’e-7, is about operational permanence. Success is measured not in footprints or flags, but in who can operate consistently, extract resources, and build lasting infrastructure.

The broader implication of Chang’e-7 is its message to the world: China is not visiting the Moon. It’s preparing to stay. Whether seen as a scientific mission, geopolitical maneuver, or technological trial run, Chang’e-7 represents a defining moment in the 21st century’s race to shape humanity’s presence beyond Earth. The Moon, once a destination, is now a staging ground, and China is making its move.