WASHINGTON — Federal health officials are unilaterally reducing the number of recommended pediatric immunizations in response to an order from President Trump, the most significant reshaping of the vaccine schedule since Trump took office and empowered health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a longtime critic of childhood shots.

Officials said the new schedule is meant to bring the U.S. recommendations closer to those in other developed nations and restore public trust in the health system. A number of other wealthy countries, including those consulted by U.S. officials, actually have similar recommendations to the ones the administration is jettisoning.

The new schedule, authorized by acting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Jim O’Neill, pares down the number of recommended vaccines from 17 to 11. It recommends some vaccines only for high-risk individuals, and says that some other vaccines, such as those for flu and rotavirus, can be given through “shared clinical decision-making.”

It follows an order from Trump, issued in early December, to examine how “peer nations” structure their vaccine recommendations.

“After an exhaustive review of the evidence, we are aligning the U.S. childhood vaccine schedule with international consensus while strengthening transparency and informed consent,” Kennedy said in a statement.

The announcement follows months of efforts by Kennedy to change the way vaccines are approved, reviewed, and recommended. Kennedy was the co-founder of the anti-vaccine group Children’s Health Defense, before leaving that role to run for president. He later gave up that bid and endorsed Trump, helping cement an alliance between the men.

Pediatricians and vaccine experts have warned that the actions the agency is taking will create chaos in doctors’ offices around the country and discourage parents from using demonstrably safe vaccines to protect their children against dangerous diseases. The American Academy of Pediatrics called the changes “dangerous and unnecessary” and said it would continue to recommend kids receive a more robust set of shots.

“This is just one more example of the decisions coming out of HHS that are sowing confusion and making it harder for people to know what to do,” said Daniel Jernigan, former director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases.

Vaccines for diseases that no longer carry a universal recommendation will still be covered by federal health insurance programs, including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Vaccines for Children program. Insurance plans sold under the Affordable Care Act will also pay for the shots. Parents who want to vaccinate their children against these diseases will not have to pay out of pocket, officials said.

It’s not clear how some private health insurance coverage could be affected over the long term. Health insurers previously said they would cover all shots that the federal government recommended as of September 1 through the end of 2026. Chris Bond, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, the primary lobbying group for health insurers, reiterated that statement on Monday.

The new vaccine schedule

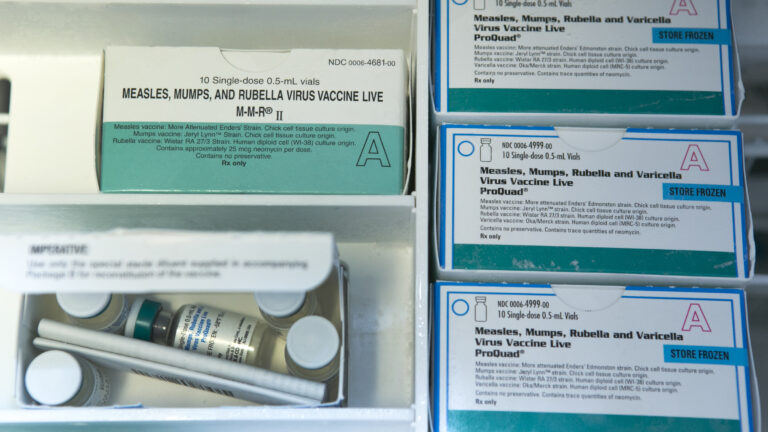

The updated schedule recommends that all children be vaccinated against diphtheria,

tetanus, pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Pneumococcal disease, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and HPV as well as varicella. However, HHS will only recommend a single dose of the HPV vaccine as opposed to two.

STAT Plus: How RFK Jr., America’s celebrity health secretary, is steamrolling science

Meningitis, hepatitis A and B, dengue, and respiratory syncytial virus vaccines will only be recommended for “high-risk” groups. For example, meningococcal vaccination is suggested for people with some medical conditions, people traveling to areas with higher rates of the disease, and first-year college students living in dorms.

(Dengue vaccine is currently only recommended for children who have had one previous dengue infection who live in a high-risk area, such as Puerto Rico and American Samoa.)

Parents will be able to choose to get their children vaccinated against rotavirus, Covid-19, flu, meningitis, and hepatitis A and B under “shared clinical decision-making.”

An unusual process

The changes to the federal vaccine guidelines came from top political officials and didn’t follow the usual process, which involves opportunities for public consideration of scientific evidence and for outside experts to weigh in.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices was not consulted on the changes, officials said, despite previously saying it would focus its efforts on the childhood vaccine schedule and vaccines recommended during pregnancy. The unusual process could leave the government vulnerable to legal challenges, some experts said.

Missed first vaccines make babies far more likely to miss measles shot, study finds

In a call with reporters, senior health officials said the former childhood vaccine schedule had contributed to declining vaccination rates and public trust in vaccines and that this new schedule would improve trust. They also said “unknown risks” of vaccination as well as limited safety data on vaccination informed their decision.

However, vaccines do undergo strict safety testing and officials have previously dropped shots when new data has pointed to severe risks. A recent study found that missing early vaccine doses made children far more likely to miss their measles shot later.

Officials said Monday that all top federal health leaders — including Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Marty Makary, National Institutes for Health Director Jay Bhattacharya, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administration Mehmet Oz — approved of the changes. Officials in these positions are not typically involved in decisions on how vaccines that have made it through the regulatory approval process are used.

To justify the changes, the administration released a 34-page review authored by Tracy Beth Høeg, acting director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research and Martin Kulldorff, a researcher who until recently was an independent vaccine adviser to the CDC, and is now chief science and data officer for HHS’ Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Høeg and Kulldorff have long opposed vaccine mandates and advocated for reducing the U.S. childhood vaccine schedule prior to their roles in government.

International comparisons

The review compares the U.S. to nations including Australia, Canada, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom. While the review claims the U.S. outpaces them in the number of recommended shots under the previous schedule, most of the named countries recommend a nearly identical list of shots. The review also doesn’t address differences between countries’ health systems, such as the fact that the U.S. does not provide universal health care.

In reality, Denmark — the country after which the new program is modeled — is actually an outlier internationally. Most peer countries recommend somewhere in a range of 13 to 16 vaccines for all children. Canada, for example, recommends 16, including shots for rotavirus and meningitis.

Why Denmark’s vaccine schedule works for Denmark — but not for the United States

Even Guinea-Bissau, a low-income East African country, recommends 12 vaccines for all its children, according to a database maintained by the World Health Organization.

Kate O’Brien, the WHO’s director of immunization, vaccination, and biologics, said she has never heard of another country stripping vaccines from its childhood schedule unless there were serious safety concerns, especially without undergoing a public process to explain the rationale for such a decision.

“I don’t know of another example of where a country has dramatically, substantially changed their immunization program. I know of no other example,” she said, noting that other countries are striving to add vaccines to their programs.

Much of the federal report is focused on declining trust in public health as well as restoring what the authors call respect for “personal autonomy.” It has little information on the scientific backing for its recommendations other than comparisons to different countries. It links declining trust in public health — which began sliding during the Covid-19 pandemic — to declining uptake in childhood vaccines, with a particular focus on vaccine mandates during the pandemic or to enter schools. Individual states set school entry mandates.

“With a few exceptions, peer nations do not have childhood vaccination mandates. They have shown that transparent and trustworthy public health authorities can achieve very high voluntary vaccination rates while preserving informed consent,” Kulldorff and Høeg wrote.

For example, when explaining their rationale for spiking the rotavirus vaccine from the schedule’s universal recommendations, the authors point to Belgium, Denmark and Portugal as not recommending it. They also write that the disease is rarely fatal in developed countries, but do not delve into the rate of hospitalizations from it. And they point out that the vaccine carries an extraordinarily rare risk of a side effect known as intussusception, or the sliding of the intestine into another part of itself.

“Reasonable people can reach different conclusions about recommending the rotavirus vaccine for all children,” the authors wrote, adding that the vaccine should not be recommended to all children in the U.S.

CDC approves new hepatitis B vaccine recommendation as some hospitals reject changes

Officials also told reporters that the recommendations were made as part of a CDC- and FDA-wide effort, but didn’t name exactly which divisions were consulted. Vaccine makers did not provide new information to inform the assessment.

New challenges for pediatricians

Changing the vaccine schedule could create new challenges for pediatricians as they consider how to advise patients on vaccines, and which shots to stock.

Jernigan said pediatricians will be hard pressed to meet the demand for extra visits the shared decision making policy will require. “ By making these vaccines a shared clinical decision making, it introduces one more barrier that prevents a child from getting a life-saving vaccine,” he said.

The WHO’s O’Brien said the hiving off of hepatitis B vaccine from the list of recommended vaccines will cause enormous problems in doctors’ offices, most of which give combination vaccines to young babies. The vaccine given to protect against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Hib, and polio includes hepatitis B. Most doctors do not stock individual shots for these diseases — in fact manufacturers don’t make enough of these vaccines in individual formulations to supply the U.S. market, experts have warned.

“I don’t know what product they think they’re going to use,” she said, noting this move could result in babies needing to get three separate injections — in multiple doctors’ visits — in place of the current combined vaccine. “It’s a curious decision to make.”

The American Medical Association, the country’s largest provider group, criticized the change in a statement.

“When longstanding recommendations are altered without a robust, evidence-based process, it undermines public trust and puts children at unnecessary risk of preventable disease,” Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, an AMA trustee, wrote.

John Crowley, president of the industry group Biotechnology Innovation Organization, was frank in his critique of the policy shift.

“Weakening recommendations for vaccines in the name of ideology over epidemiology undermines America’s leadership in public health and trust in our health authorities,” Crowley said in a statement. “It stokes fear and confusion among parents and health care providers. Most importantly, instead of making America healthy again, these actions increase the risk of serious illness for all Americans, especially children.”

HHS had intended to announce these changes at the end of last year but the announcement was delayed due to scheduling conflicts as well as concerns about the legality of the move, an official familiar with the plans but not authorized to speak publicly told STAT.

The legality of the move is still up in the air, legal experts told STAT. Richard Hughes, a lawyer with Epstein Becker Green, noted that federal statute requires the government not act in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner. Hughes, who is the lead counsel in a lawsuit challenging Kennedy’s decision to remove the Covid-19 vaccine from the childhood schedule, argued that the agency’s sudden changes to the schedule could be just that.

“They’re not conducting a systematic review of any kind of literature, any kind of evidence,” said Hughes. “They’re not doing anything that is even remotely close to what the ACIP would do.”

iI’s not clear whether the scientific report authored by Høeg and Kulldorff will will stand up in a court, in part due to their past views on vaccines..

“Secretary Kennedy has ultimate authority to make recommendations on vaccine schedules, but he has to go through a deliberative, evidence-based process,” said Lawrence Gostin, a global health legal expert at Georgetown University. “He is short circuiting the normal process for making scientific recommendations from the federal government.”

Gostin said he has no doubt there will be litigation. He said he has worked with HHS and the CDC for four decades and “has never seen anything like this.” But it’s not clear whether litigants would be successful.

Cary Coglianese, an administrative legal scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, said that legal challengers must prove they have been harmed by an agency action. It might be difficult to quantify harm, particularly if insurance coverage doesn’t change.

“Courts will generally defer to agencies on matters of expert judgment,” Coglianese said. “The challengers will thus likely have their work cut out for them to convince a court that the agency has erred.”

States and colleges will still be able to mandate vaccines, but red states in particular may follow HHS guidance. The result would be a checkerboard of vaccine regulations, which could mean gaps in national protection against pathogens.

“There’s going to be massive confusion,” Gostin said. “Insurance companies will be confused. Patients will be confused. States will be confused.”

Lizzy Lawrence, Isabella Cueto, and Bob Herman contributed reporting.