Borruso exploits ekphrasis as a way to generate a conversation with a work of art, like the above referenced Salvador Dalí painting, or artistic technique, such as voice-over or the dolly shot to guide or direct our readerly attention. Poems such as “Scorsese Dreamsong” achieve both effects, shifting from film analysis to autobiography in the terse rhythms patterned by ornamental couplets. Hardly any of Splice’s poems take up more than a single page, and though each of them across the book’s four sections (and one “Post-credits Scene”) flex their author’s erudition, casting an unabashedly worldly gaze, Borruso never strays from the interiority that sculpts his Splice: the body and its insecurities and uncertainties, as when, in “Resonance Imaging,” his speaker awaits diagnosis while traveling, through sound wave’s association, to all the capitals he can remember off the top of his head—“the spin,” he writes, “of my mind’s / vinyl.” “Yes, geography will save me.”

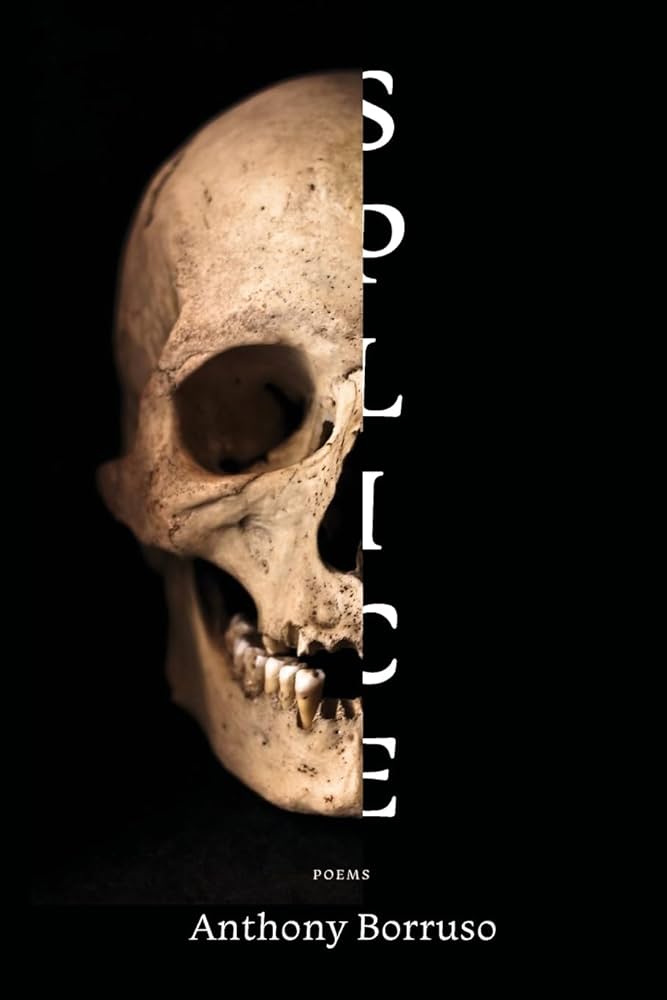

The body—and all its moving and moveable parts—is on the author’s mind; so, too, are the deficiencies and failures that so often make us slip, sometimes productively, into other registers or frequencies. Cohering the speakers’ diatribes on plot vs. style, performative activism and the poet as a lifestyle brand, gentrification, new age folk philosophy, the “act of love,” and the “art of feigning knowledge” are the inner workings and breakdowns of the body: deviated septums, inner ear conditions, migraines, macular degeneration, the careful work of kidneys, and craniotomy speckle the collection with sensory goo or glue. Again and again, Borruso mends any mind/body problem through his adroit implementation of splice, most poignantly in the moments of rehearsal and playback of the open-skull surgical calisthenics his own body endured, emblematized by the severed skull on the book’s cover. In “Self-Portrait With an Open Skull,” Borruso’s speaker begins by cataloging the details of sensation and the room in which he’s been placed, “face-down,” prior to the procedure. Though it only takes two stanzas for the gaze of cinema to rush in and infect memory with its technological mediation:

Godly cinematographer,

get that dolly shot

in the subway, show a rat

trekking a slice of pizza down

the tracks. This is where

one goes when the lights go

out.

Splice’s poems can be characterized by turns—and sometimes all at once—as vulnerable, witty, satiric, and inquisitive. With cutting vulnerability and brutal clarity welded by third-wall implosions, Borruso achieves the spacey, bedazzled effect of a late-night Netflix tryst, in which any static picture is prone to moving (and talking) if you allow yourself to linger, or forget that you’ve been looking. If there’s an artist statement smuggled in Borruso’s mosaic of clips cut up, grafted, and rearranged, it’s in “Ode to R. Budd Dwyer,” another requiem that speaks, also, to the poet’s preferred methods of confession and composition:

To have two mouths, one for singing

and one for screaming bloody murder—this is what the poet strives for, to speak

from the temples. Still, I promise no spectacle,I will not make of me a puzzle, a humpty-

dumpty-put-back-the-pieces affair.

In an age of AI generated legibility and one-click solutions escorted by algorithmic advertising, Borruso’s auspicious debut is a clarion call for complexity, nuance, ambiguity, and the plenitude that arises from fragmentation.