Almost 7 million Australians living on the fringes of capital cities are at a growing risk from fires, according to a new report compiled by former fire chiefs and the Climate Council.

The risk could be similar to a major fire like the one that ravaged Los Angeles, killing 31 people last year.

The report had five key findings:

- The LA neighbourhoods were “supercharged” by climate change in the middle of winter.

- The outskirts of Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Adelaide, Perth and Hobart share the same “dangerous characteristics” that made the LA fires so destructive.

- More people than ever are living in harm’s way on the outer fringes of our cities.

- Pollution is “turbo-charging Australian fire conditions and it’s making fires more frequent, costly, intense — and less predictable”.

- Climate-fuelled fires are increasingly exceeding the limits of modern firefighting.

Greg Mullins is the former commissioner of Fire and Rescue New South Wales and the founder of Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. He also co-authored the paper.

Homes were lost when fires burned more than 6,000 hectares in the Pacific Palisades neighbourhood of Los Angeles last January. (AP: Eugene Garcia)

“I’ve worked with Los Angeles City and Los Angeles County fire departments in the past and fought fires in Los Angeles,” he said.

“We’ve written this report … analysing if could that happen here, and unfortunately this answer is definitely yes because of the impacts of climate change, because of worsening fire weather, lengthening fire seasons and just the wild swings in climate that we’re seeing.”

Loading…

The report also found that over the coming decades, further climate change would “stack the odds in favour of” more dangerous fire weather.

An increase in intense bursts of rainfall, followed by long dry periods, would create more opportunities for bush and grass fires to take hold and spread rapidly, the report said.

“Every capital city, with the exception of Darwin, is at risk, so the outskirts of Sydney but even the satellite cities like the central coast, Newcastle, Wollongong … Canberra … Queensland,” Mr Mullins said.

A satellite image over a neighbourhood in Los Angeles, showing hundreds of homes burning. (Maxar Technologies/Handout via Reuters)

University of Tasmania fire science professor David Bowman said Australia had been “incredibly lucky” so far.

“There are some significant differences [between Australia and the United States] … in terms of the climatology, the fire weather patterns and also the type of urban development,” he said.

“But there’s absolutely no reason to exclude the possibility of a major fire ever impacting an Australian town or the outer edge of an Australian city, penetrating into suburbs that would normally not be considered prone to bushfires.

The Pacific Palisades fire in Los Angeles was declared the most destructive in the city’s history. (ABC News: Cameron Schwarz)

“We haven’t had anything like LA but that doesn’t mean it can’t happen.”

One of the shocking things about the LA fires was that they happened in the middle of winter, with Professor Bowman saying high temperatures were not necessary to have uncontrolled fires.

He said a local example was the recent fire in Dolphin Sands on Tasmania’s east coast, which destroyed 19 homes.

It was concluded that the Dolphin Sands fire was sparked by a registered burn that was not extinguished properly. (Supplied: Gynes Ramsbottom-Isherwood)

“Very strong winds can set up fires, and once they get going, they’re sort of like a giant hair dryer. They can start drying the fuel out in front of them,” he said.

“The other factor that comes into this is that once you get these ignitions, fires can actually start generating their own wind.”

The other big factor, Professor Bowman said, was something called “hydro climactic whiplash”.

“The climate is very, very unstable and it’s like we’re being dealt really surprising cards all the time now,”

he said.

“We have wind-driven fires and then the winds will go away. Then you might get a heatwave and then you might get flooding rain and the last thing on your mind is fire and then a huge drought comes back.

“So we’re getting this incredible, like very-dynamic, unstable climate.

“One of the consequences of that means it’s harder to forecast and predict.”

‘It’s worse than we thought’

Amy Blain, who is a member of the People’s Climate Assembly and Bushfires Survivors for Climate Action, lived through the fires in Bermagui in New South Wales at the end of 2019.

She remembers opening the blinds at 7am in the morning and just looking out to pitch black.

The NSW fire was “a pretty horrendous experience” for Amy Blain and her family. (Supplied: Amy Jowers)

Coming from the UK it was her first experience of a bushfire.

“

Friends were texting saying ‘are you evacuating?’ she said.

“The filtration plant was damaged, the telcoms were damaged and we had a newborn at the time.”

Ms Blain recounts driving back to Canberra where at times the smoke was so thick she could barely see the tail lights of the car in front.

They made it home safely but then had to deal with a “smoke-filled existence”.

“It was a very, very stressful start to the year and we couldn’t get air filters.

“All of our doors in the rental weren’t particularly well insulated, the windows were terrible and it was just leaking smoke, so we had sheets that were wet and were regularly making those damp to try and keep the smoke out.

“It was a pretty horrendous experience.”

Living in Canberra — where 487 houses were destroyed by fire and four people killed just over two decades ago — Ms Blain said many people were aware that major cities were not immune to major fires.

But she is concerned the city is still underprepared and wants more to be done to address the pollution that is contributing.

“What we’ve seen so far is horrendous. It’s worse than we thought. We’re seeing cities on fire in winter,”

she said.

“Why would we be adding to that? We’ve been told no more. That should be an absolute.”

Reducing risk for the future

Water is dropped on the LA Pacific Palisades fire in January 2025. (AP: Ethan Swope)

To avoid a repeat of the LA fires, the report puts forward three “key areas of focus” that could help reduce fire risk in Australia.

The first of these is cutting pollution more deeply and swiftly both in Australia and across the world.

It is then suggested that Australia invests heavily in disaster preparation and community resilience across all levels of government.

The final area of focus would be building emergency service and land management capacity at areas in cities and towns where the bush interacts with urban infrastructure.

With strong investment from state and territory governments into these key areas of focus, the report said Australia “could still control the future fire risk curve”.

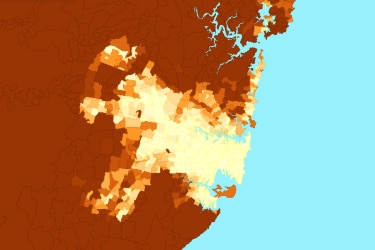

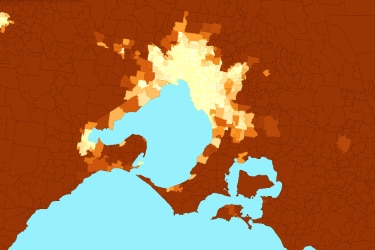

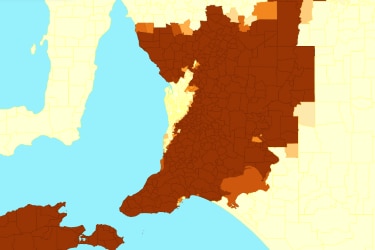

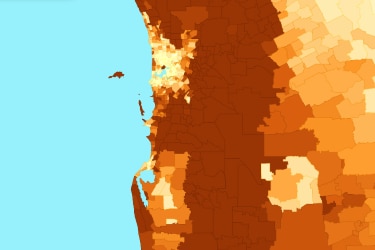

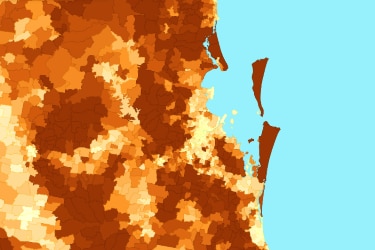

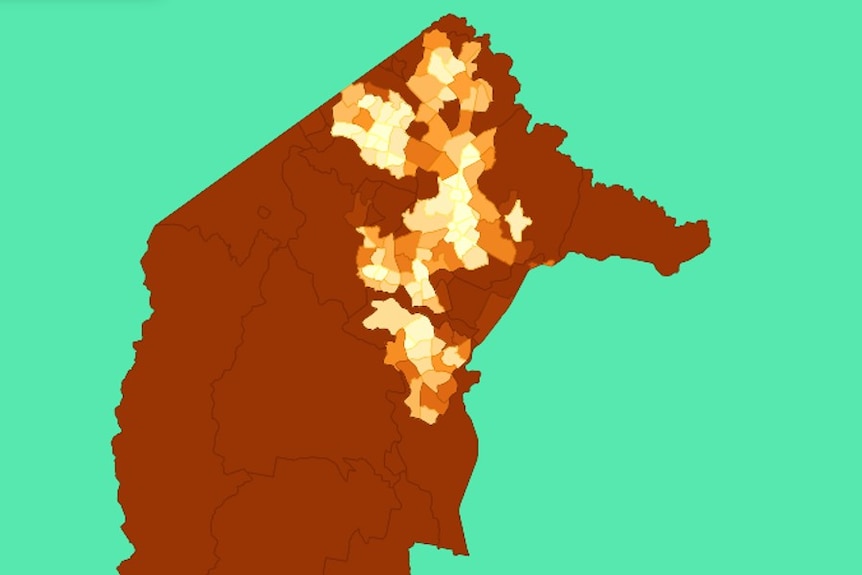

Bushfire risk in our cities

The following maps show the bushfire risk in Australian cities, with darker areas indicating greater risk.

Sydney. (Supplied: 360info)

Melbourne. (Supplied: 360info)

Adelaide. (Supplied: 360info)

Hobart. (Supplied: 360info)

Perth. (Supplied: 360info)

Brisbane. (Supplied: 360info)

ACT. (Supplied: 360info)