For the first time, astronomers have directly measured the mass of a rogue planet, a celestial body wandering through space without a star. The object, comparable in size to Saturn, was studied through a rare and powerful cosmic alignment, revealing its mass with unprecedented precision.

This finding, published in Science, marks a significant step forward in the study of free-floating planets, which are notoriously difficult to detect and analyze. Without a parent star, such planets don’t emit detectable light or follow observable orbits, leaving scientists with few options for investigating them.

Bending Starlight to Weigh a Planet

The discovery was led by Subo Dong of Peking University, using a method called gravitational microlensing. The team capitalized on an exceptional alignment between the rogue planet, a distant background star, and two observation points: Earth and the Gaia space telescope.

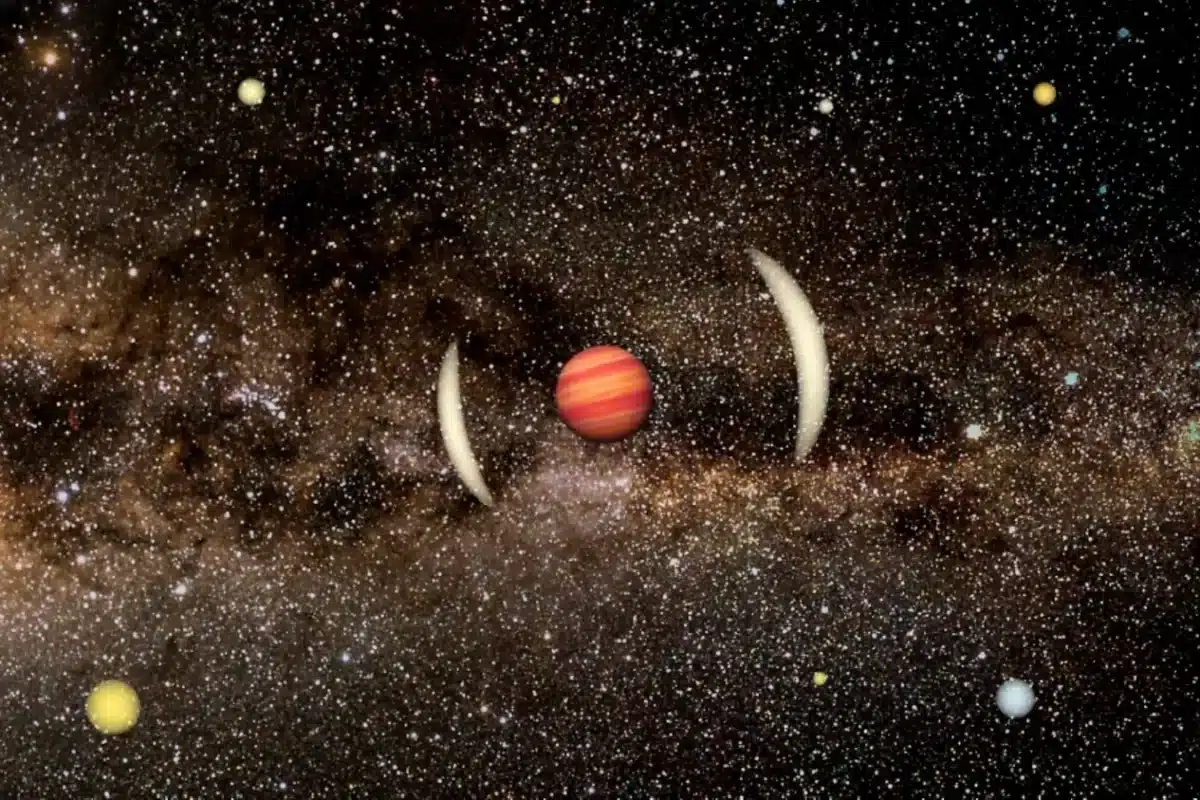

Artist’s impression of a rogue planet distorting starlight through gravitational lensing. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE

Artist’s impression of a rogue planet distorting starlight through gravitational lensing. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE

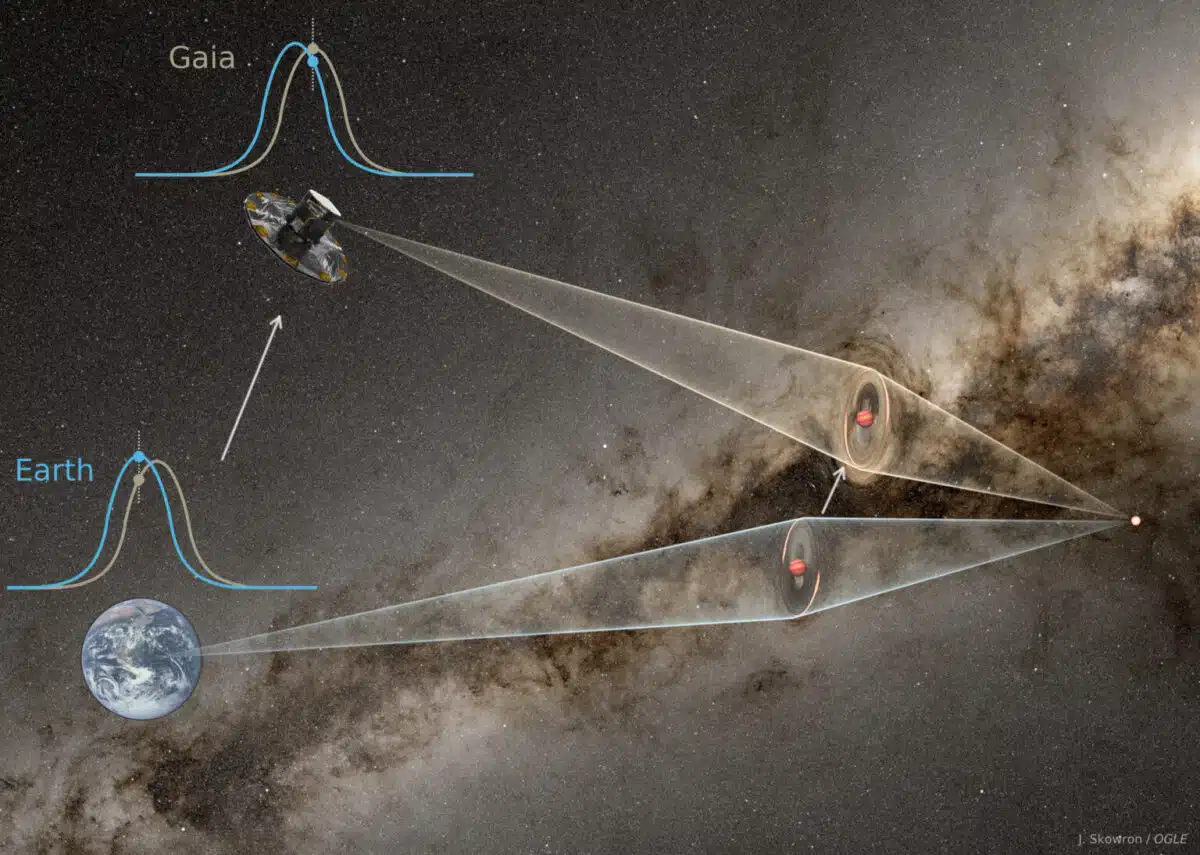

The technique at the heart of this discovery, gravitational microlensing, relies on the warping of spacetime by massive objects. When the rogue planet passed directly between Earth and a distant star, its gravity briefly magnified the star’s light. According to the latest research, the event was detected simultaneously from Earth and from the now-retired Gaia observatory, enabling scientists to measure the planet’s gravitational effect from two different angles.

This method bypasses the need for a free-floating world to orbit a star, normally essential for determining mass through orbital dynamics. In this case, the team could instead triangulate the planet’s location and mass based on the delay and strength of the light distortion seen from both perspectives.

Lonely Giants Adrift in the Dark

Rogue planets, also called free-floating planets, are planetary bodies that don’t orbit any star. They likely formed in a star system but were later ejected due to gravitational interactions. Since they emit no light of their own and lack the illumination of a nearby star, spotting them is extremely rare. This invisibility has kept them largely out of reach, until now.

Diagram showing how lensing caused a brightness change, measured by Gaia and Earth-based telescopes to calculate mass and distance. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE

Diagram showing how lensing caused a brightness change, measured by Gaia and Earth-based telescopes to calculate mass and distance. Credit: J. Skowron, K. Ulaczyk / OGLE

The successful measurement of this Saturn-sized rogue offers a rare opportunity to study such objects in detail. With no orbit to examine and no reflected starlight to analyze, the breakthrough confirms that microlensing may be one of the few tools capable of unlocking the secrets of these distant nomads.

Measuring the Invisible

Determining the mass of the celestial body with no star is no small feat. According to the team’s findings, the researchers relied entirely on the microlensing data from the momentary alignment. The data captured from Earth and Gaia allowed them to estimate the object’s mass by observing how much it bent the background star’s light, effectively using gravity itself as a scale.

Gavin Coleman, a postdoctoral researcher at Queen Mary University of London and author of a supporting analysis published in Science, emphasized the significance of the breakthrough:

“What’s really great about this work, and really noteworthy, is that it’s the first time we’ve got a mass for these objects.” He noted that this achievement was possible “purely because the authors had both ground-based observations and Gaia, looking at observations from two different places.”

The precision of this result marks a methodological leap in the field of exoplanetary science. It opens up the possibility of examining other rogue planets with similar techniques, especially as new telescopes and missions, like Gaia‘s successors.