On July 29, 2025, the world’s sixth biggest recorded earthquake struck Russia, triggering a tsunami whose waves reached as far as the U.S.’s West Coast. Data from an unexpected source—space—has shed unexpected light on this oceanic reaction.

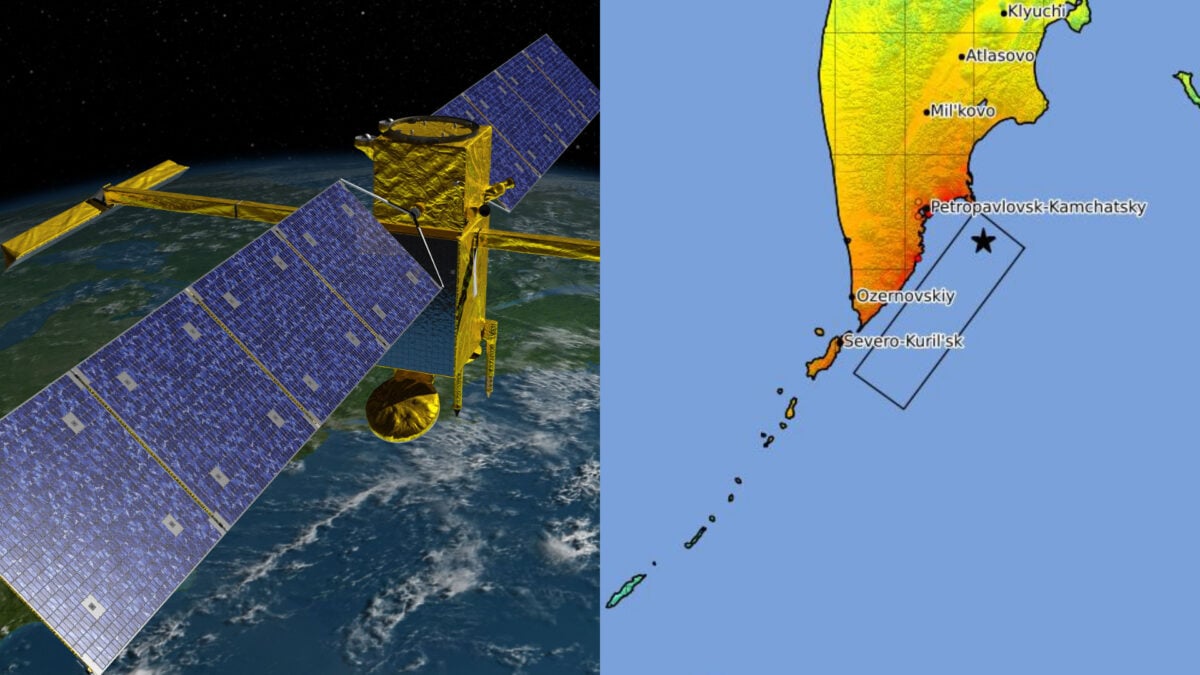

The Surface Water Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite, whose aim is to survey the planet’s surface water, documented the first high-resolution track of a significant subduction zone tsunami from space, a team of researchers claims in a study published last November in the journal The Seismic Record. This information could shed light on how tsunamis move and potentially impact coasts.

“[We] had been analyzing SWOT data for over two years understanding different processes in the ocean like small eddies, never imagining that we would be fortunate enough to capture a tsunami,” Angel Ruiz-Angulo, co-author of the study and a Physical Oceanographer at the University of Iceland, said in a statement by the Seismological Society of America.

Your tsunami nightmares are inaccurate

When you think of a tsunami wave, chances are you imagine a single terrifying wall of water advancing all at once. In fact, since a large tsunami’s wavelength is significantly greater than the ocean’s depth, researchers typically deem them “non-dispersive.” In other words, scientists predict the wave will move as a single cohesive unit and not fragment into a number of propagating waves. SWOT’s data, however, revealed that the tsunami triggered by Russia’s magnitude 8.8 earthquake didn’t propagate as a single wave but as a complex movement of interacting waves.

This calls into question the notion that large tsunamis are non-dispersive, explained Ruiz-Angulo. In fact, he and his colleagues noted that computer models of tsunamis that accounted for dispersion better aligned with the real satellite data than standard models.

“The main impact that this observation has for tsunami modelers is that we are missing something in the models we used to run,” he added. “This ‘extra’ variability could represent that the main wave could be modulated by the trailing waves as it approaches some coast. We would need to quantify this excess of dispersive energy and evaluate if it has an impact that was not considered before.”

Refined estimates of the Russian quake

The team merged the satellite measurements with data from Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) buoys on the tsunami’s route.

“I think of SWOT data as a new pair of glasses,” explained Ruiz-Angulo. “Before, with DARTs we could only see the tsunami at specific points in the vastness of the ocean. There have been other satellites before, but they only see a thin line across a tsunami in the best-case scenario. Now, with SWOT, we can capture a swath up to about 120 kilometers [75 miles] wide, with unprecedented high-resolution data of the sea surface.”

Nevertheless, the buoys helped refine the original estimates of the earthquake. The team found that the tsunami arrival times estimated by previous simulations didn’t align with the real-life data from two DART tide gauges. As such, the researchers took another look at the original earthquake by employing the buoy information in a type of analysis called inversion. This approach indicated that the rupture stretched south more than researchers believed and was around 250 miles (400 kilometers), which is also strikingly longer than other computer models suggested.

Since the monstrous magnitude 9.0 2011 earthquake in Japan, co-author Diego Melgar’s lab and others have attempted to incorporate DART information in inversions. However, because the models necessary to simulate DARTs differ significantly from the ones necessary for data from the solid ground, this doesn’t happen all the time, Melgar explained. “But, as shown here again, it is really important we mix as many types of data as possible.”