A newly discovered galaxy cluster, blazing with unexpectedly hot gas just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, is forcing scientists to rethink the early universe. The research, published in Nature, reveals thermal conditions that challenge standard cosmological models, suggesting the presence of powerful early mechanisms shaping massive structures far earlier than predicted.

Unprecedented Temperatures In An Infant Cluster

In one of the most startling discoveries in recent astrophysics, researchers have identified a galaxy cluster with gas temperatures that far exceed expectations for its age. Named SPT2349-56, the cluster lies approximately 12 billion light-years away, allowing astronomers to observe it as it appeared when the universe was just 1.4 billion years old. Using data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an advanced telescope array partly developed by Canada’s National Research Council, the team detected the Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect, a signature indicating the presence of hot ionized gas between galaxies.

Lead author Dazhi Zhou, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia, expressed his surprise at the data:

“We didn’t expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” he said. “In fact, at first I was skeptical about the signal as it was too strong to be real. But after months of verification, we’ve confirmed this gas is at least five times hotter than predicted, and even hotter and more energetic than what we find in many present-day clusters.”

These findings pose a serious challenge to current theories of galaxy cluster formation, which suggest such high temperatures emerge only in more evolved clusters, typically billions of years later in cosmic time.

The Role Of Supermassive Black Holes

The study points to a likely culprit behind the extreme heating: three recently discovered supermassive black holes embedded within the cluster. These massive engines appear to have already been active in the early universe, injecting tremendous energy into the intracluster medium. According to Dr. Scott Chapman, a co-author and professor at Dalhousie University, this level of energetic feedback was completely unexpected at such a young cosmic age. “This tells us that something in the early universe, likely three recently discovered supermassive black holes in the cluster, were already pumping huge amounts of energy into the surroundings and shaping the young cluster, much earlier and more strongly than we thought,” he explained.

Such early black hole activity could explain how proto-clusters like SPT2349-56 evolved so rapidly. The cluster already contains over 30 star-forming galaxies, collectively producing stars at a rate 5,000 times faster than the Milky Way, within a compact region measuring around 500,000 light-years across. The findings indicate that galaxy clusters may form, and heat, much earlier than standard cosmological simulations have allowed, calling for revisions to current models of structure formation.

A New Era Of Galaxy Cluster Research

This discovery, published in Nature, marks a significant shift in our understanding of how galaxy clusters develop. Traditionally, clusters are thought to accumulate gas slowly through gravitational attraction, which then heats up over billions of years due to mergers and accretion shocks. But the sheer intensity of the heat observed in SPT2349-56, along with its dense core of active galaxies, suggests that internal mechanisms, such as AGN feedback from supermassive black holes, may dominate earlier than anticipated.

“Understanding galaxy clusters is the key to understanding the biggest galaxies in the universe,” said Dr. Chapman. “These massive galaxies mostly reside in clusters, and their evolution is heavily shaped by the very strong environment of the clusters as they form, including the intracluster medium.” The Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect used to analyze this cluster offers a valuable tool for probing such conditions, even at great distances and early epochs.

The new findings provide astronomers with an early glimpse of the complex physics governing cluster formation, and highlight the importance of multi-wavelength observations and international collaboration in exploring the early universe. With instruments like ALMA continuing to push the boundaries of detection, more unexpected revelations are likely to follow.

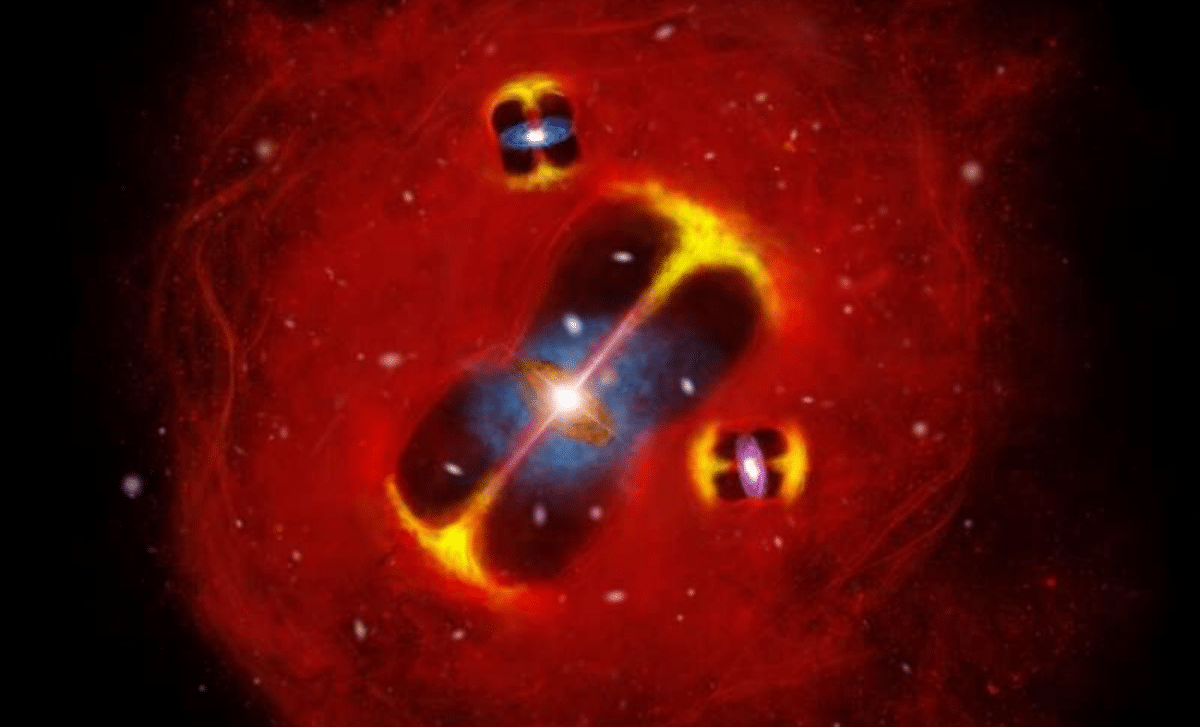

An artist’s impression of molecular gas in the intracluster medium of SPT2349-56. (MPIfR/N.Sulzenauer/ALMA)

An artist’s impression of molecular gas in the intracluster medium of SPT2349-56. (MPIfR/N.Sulzenauer/ALMA)

A Glimpse Into A Violent Young Universe

The case of SPT2349-56 serves as a window into a more violent, chaotic early universe than previously imagined. Rather than a slow, gradual formation of structure, the data point to intense, localized heating and rapid star formation driven by powerful central black holes. This not only alters the timeline of cluster development but may also influence how astronomers estimate the mass, age, and evolution of early galaxies.

What remains unclear is how common such systems might be. If SPT2349-56 is an outlier, then it’s a fascinating cosmic anomaly. But if other similar systems are found in future surveys, researchers may have to rewrite the fundamental rules of how large-scale structures formed after the Big Bang. As the search continues, one thing is certain: the early universe was far more energetic and dynamic than we thought.