Dallas has made the erasure of its built heritage something of a civic tradition. Entire neighborhoods have been virtually wiped off the map, among them La Reunion, the short-lived socialist enclave founded in Oak Cliff in the 1850s. Minority communities (Little Mexico, Little Jerusalem, several freedmen’s towns) have proved to be particularly vulnerable.

Demolitions have been a special plague on downtown, once a dense and vibrant hub now marked by empty surface lots and desolate stretches of automotive infrastructure. It is deeply ironic that City Hall might be destroyed in a misguided effort to revive the downtown core. Unwilling to learn from history, Dallas seems doomed to repeat it.

Historian Mark Doty’s Lost Dallas, published in 2012, is a useful compendium of the city’s demolished architecture, though it is now sadly out of date — it would need near-constant updates to remain current, given the city’s turnover.

To follow is my list of 20 of the city’s most notable demolitions, a list that could be expanded exponentially without much effort. Have a nomination? Add it to the comment section below.

News Roundups

The first Dallas City Hall.

Dallas Morning News / Dallas Morning News

The first Dallas City Hall

Dallas has a history of demolishing its city hall. Its first, designed by the St. Louis architects Bristol & Clark, opened in 1889 and was a brick and stone mini-fortress with spiky finials projecting over its roofline. It was demolished in 1910 to make way for the Adolphus Hotel.

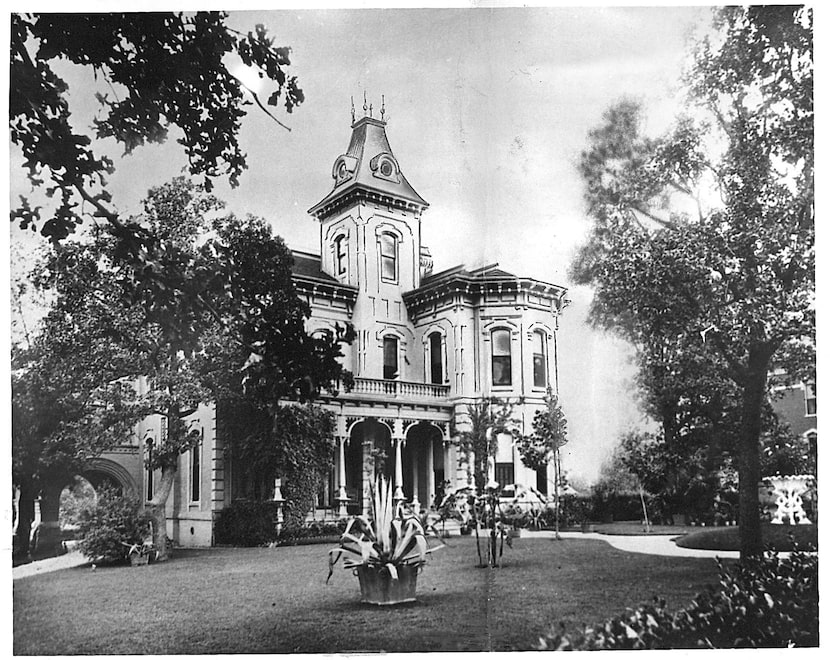

An undated photo of the demolished Ross Avenue residence of Jules E. Schneider.

Dallas Morning News / Dallas Morning News

Ross Avenue Mansions

In the early 20th century, the stretch of Ross Avenue leading into downtown was lined by mansions built for the city’s elite. Only two remain, the Belo Mansion (now home to the Dallas Bar Association and victimized by an atrocious expansion) and the former Alexander Mansion (now the Dallas Woman’s Forum).

An undated photo of the Oriental hotel.

Dallas Morning News / Dallas Morning NewsDallas Mornin

The Oriental Hotel

The resplendent Victorian hotel was so over-the-top lavish when it opened in 1893 that it was dubbed “Field’s Folly,” for developer Thomas Field (namesake of Field Street), who required a financial bailout from St. Louis beer baron Adolphus Busch. It was demolished in 1924 to make way for the Baker Hotel. Also gone, and with more dire consequences: the Interurban streetcar system seen in operation in the above photo.

The demolished Hall of Negro Life at Fair Park.

Dallas Historical Society / Dallas Historical Society

The Hall of Negro Life

Fair Park is defined by the buildings erected for the Texas Centennial Exposition of 1936. But several of the pavilions created for that exhibition were demolished, chief among them the Hall of Negro Life, dedicated to African American history and achievement. From the outset, the building was unwanted by the fair’s white establishment, and was intentionally obscured behind shrubs. It was demolished before the exposition was reopened for its second year, in 1937.

Elm Street’s theater row in 1942.

Arthur Rothstein

Elm Street Theater Row

There was a time when Elm Street was lined with grand theaters and movie houses — the Capital, the Melba, the Leo, the Palace, the Rialto — making it the Dallas version of New York’s Great White Way. Now there is just one: the Majestic, which continues to justify its name.

The Baker Hotel in the 1930s.

The Dallas Morning News

The Baker Hotel

The 18-story, 700-room Baker Hotel was designed by St. Louis architect Preston Bradshaw for the developer T. B. Baker on the site formerly occupied by the Oriental Hotel. It opened in 1925 and earned a place in American history during the 1960 presidential campaign, when a conservative mob accosted Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson as they were leaving the hotel. It was imploded in 1980 to make way for what is (at least for now) the headquarters of AT&T.

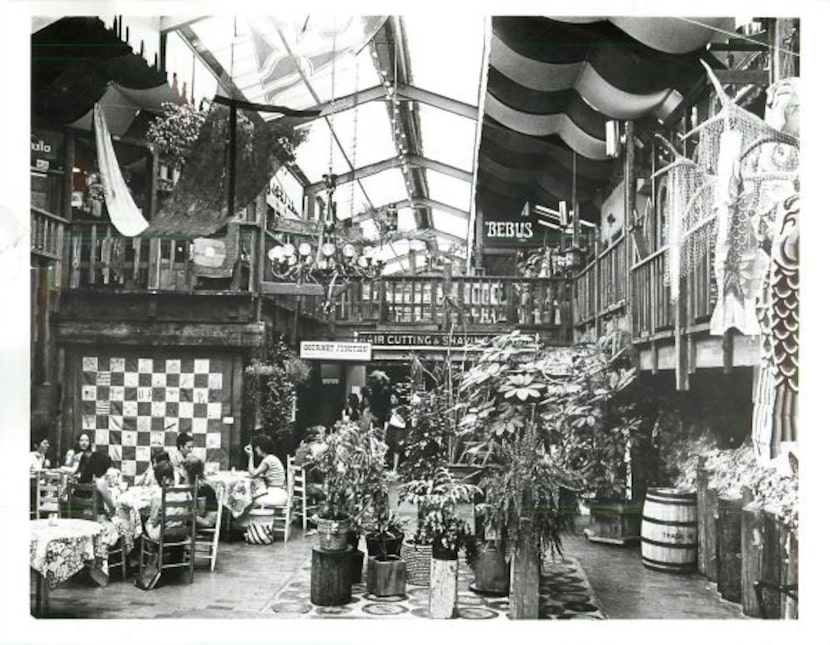

Interior of the Olla Podrida marketplace.

The Dallas Morning News

Olla Podrida

The beloved mall for local artists and craftsmen (olla podrida translating roughly to “a bit of everything”) opened in 1972 in a vacant North Dallas warehouse transformed by the inventive Dallas architects Pratt, Box & Henderson. Its multilevel arcades were crossed by catwalks and lit by skylights, all built with recycled materials. It was demolished in 1996. The firm’s Quadrangle shopping center in Oak Lawn — modeled on the architecture of Santa Fe — was demolished in 2022.

The Dallas Apparel Mart, designed by Pratt, Box & Henderson.

File Photo / digital file

Apparel Mart

This fashion industry trade hall, also designed by Pratt, Box & Henderson, had a curvy, multilevel atrium with hanging gardens. The futuristic building, which opened in 1964, achieved on-screen immortality as the principal location for the sci-fi thriller Logan’s Run. It was demolished in 2004.

Aerial view of the Dr Pepper Plant in 1973.

TOM DILLARD/Staff Photographer / Dallas Morning News

Dr Pepper Headquarters & Bottling Plant

The elegant art deco home of the city’s favorite (nonalcoholic) beverage was designed in 1946 by Thomas, Jameson & Merrill Architects. The sprawling complex was fronted by a soaring lobby set behind a circular drive. A preservation campaign that made national headlines failed to save the building, which was razed in 1997 to make way for the Mockingbird Station development.

The demolition of Texas Stadium in 2010.

GARY BARBER / Dallas Morning News

Texas Stadium

Remember when the Cowboys were good? Back then they played in this stadium (technically, in Irving), notable for its open roof — “so God can watch His favorite team play,” according to linebacker D.D. Lewis. The stadium was designed by Dallas architect A. Warren Morey and opened in 1971. Among its innovations was its ring of luxury suites. Demolished in 2010.

The Praetorian, once the city’s tallest building.

Dallas Morning News / Dallas Morning News

Praetorian Building

The city’s tallest building when completed in 1924, the handsome downtown tower was remodeled to ill effect in the 1950s and pulled down by developer Tim Headington in 2012. The building site is now a private lot occupied by artist Tony Tasset’s kitschy eyeball sculpture. Other notable lost downtown towers include the American Exchange National Bank (1918-1981), Cotton Exchange (1925-1994), Medical Arts (1923-1979), Southland Life (1918-1980) and Southwestern Life (1913-1972) buildings.

Historic buildings being demolished on Main Street in 2014.

Harry WIlonsky / Dallas Morning News

Main Street Group

After taking down the Praetorian, Headington razed a group of neighboring buildings dated to the late nineteenth century and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The first demolition took place during a Cowboys game on a Sunday in 2014. The buildings were replaced by the luxury department store Forty Five Ten.

A former fellowship hall in the 10th Street Historic District slated for demolition in 2019.

Tom Fox / Staff Photographer

10th Street Historic District

It is something close to a miracle that anything remains of Oak Cliff’s 10th Street Historic District, once a flourishing freedmen’s town. Despite its landmark designation, it has been subject to a spate of demolitions, many ordered by the city in the name of safety, and over the objections of preservationists.

O’Neil Ford’s Penson House in Highland Park.

Ting Shen / Staff Photographer

Penson House

Any number of modernist homes built in the mid-century could be added to this list. Relatively modest in scale and appearance, they have frequently been replaced by larger, more ostentatious designs. The work of O’Neil Ford, the father of Texas modernism, has been especially prone to this fate. In 2016, his Penson House, on a prime Highland Park corner, was sold and demolished. Three years earlier, the Tinkle Residence (built for Morning News book critic Lon Tinkle), was torn down. It was one of several Ford-designed houses in the so-called Culture Gulch of University Park.

Grayson Gill’s Great National Life Building.

Courtesy / Dallas Public Library

The Great National Life Building

One of the city’s mid-century modern jewels, this 1963 office building was designed by architect Grayson Gill for the Great National Life Insurance Co. and was later occupied by the Salvation Army. It was fronted by a distinctive metal screen of tetrahedral panels. It was demolished in 2018.

The so-called Leaning Tower of Dallas

Vernon Bryant / Staff Photographer

The Leaning Tower of Dallas

Nothing has quite so artfully epitomized Dallas demolition culture run amok as the failed implosion, in February 2020, of this 11-story office tower adjacent to the Central Expressway. The core of the 1971 concrete building refused to come down, drawing crowds of gawkers and becoming an internet sensation and civic embarrassment. A wrecking ball eventually completed the job.

The old Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Trestle Bridge seen behind the DART line bridge over the Trinity River.

Tom Fox / Staff Photographer

Santa Fe Trestle Bridge

A vestige of Dallas history, the cross-timbered Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe trestle bridge was built in 1934, on a site occupied by railroad bridges dating back well into the 19th century. The beautiful wooden structure was taken down in 2021 by order of the Army Corps of Engineers, who deemed it an impediment to the flow of the Trinity River and potential flood hazard.

Atlas Metal Works on Singleton Boulevard dated to the 1920s.

Shafkat Anowar / Staff Photographer

Atlas Metal Works

One of the most significant works of early 20th-century industrial architecture in Dallas. It was on the prime corner of Singleton Boulevard and Sylvan Avenue in West Dallas, and was familiar for its distinctive gabled roofline and beautifully faded wall signage. It was razed in 2024 to make way for generic apartments.

The Braniff (left) and Exchange Bank (right) buildings in Exchange Park.

Exchange Park

This pioneering mid-century office park designed by Dallas-based Lane, Gamble & Associates opened in 1956. It was pitched as “America’s City of Tomorrow” and came with a retail mall at its ground level. A pair of towers, one for Exchange Bank and a second for Braniff Airlines (which opened in 1958), was enlivened by yellow and blue exterior panels and distinctive boxy sunscreens. The development was taken down in 2024 to make way for a new children’s hospital.

The Cox Mansion in Highland Park.

Courtesy Edwin L. Cox estate

Cox Mansion

A series of demolitions have plagued Highland Park’s tony Beverly Drive in recent years, but the razing of the Cox Mansion stands out for its disregard for history. The colossal 1912 Italianate residence, designed by Herbert M. Greene, was taken down in 2024 by billionaire Andy Beal so he could build a new mansion.

Related

Related