Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

One of the most fascinating things about the Universe is that whenever we look at it in a novel way — in new wavelengths of light, with greater resolution, or with superior sensitivity — we give ourselves the opportunity to be surprised. Instead of merely finding fainter or more distant versions of what we had already established was out there, we often find things that we didn’t even know we ought to be looking for previously. They might include new classes or populations of astronomical objects, an unexpected abundance of what were previously thought to be rare occurrences, or the presence of something that wasn’t expected to exist under the conditions or with the properties we wound up observing.

That’s definitely the case when it comes to the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST, which is our largest, most powerful space telescope ever designed, launched, and operated. In particular, with its superior infrared capabilities, JWST has revealed to us a plethora of ultra-distant galaxies: including nearly all of the currently most-distant astronomical objects. While the most discussed puzzles about these ultra-distant galaxies has been their great abundance and extreme brightness, another aspect that’s just as puzzling is their dust content. In particular, with so little star-formation having occurred over such a short time period, the key question is, “how do these galaxies make so much dust, and so soon?”

In a remarkable new study led by Elizabeth Tarantino, we may have just discovered the answer in a counterintuitive way: by examining the dust within a galaxy right in our own cosmic backyard. Here’s the fascinating story.

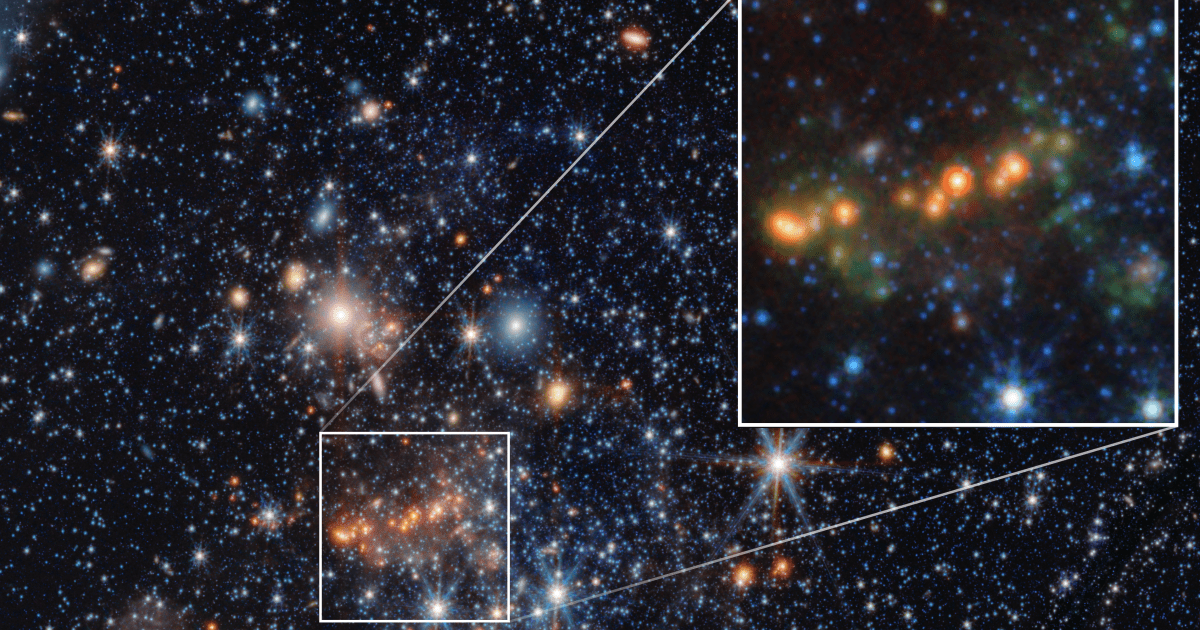

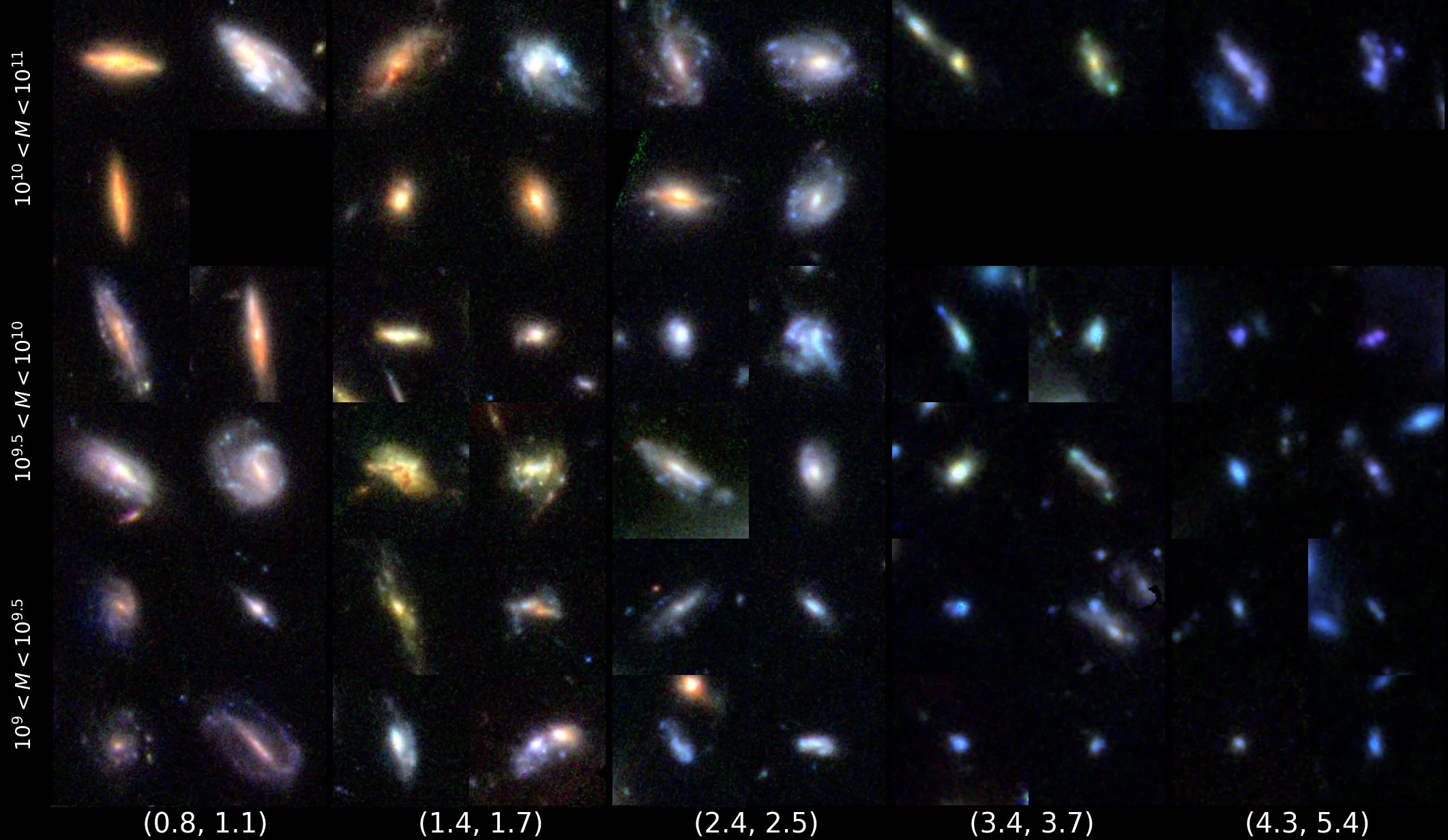

This selection of 55 galaxies from the JWST’s GLASS Early Release Science program spans a variety of ranges in redshift and mass. This helps teach us what shapes galaxies take on over a range of masses and stages in cosmic time/evolution, revealing a number of very massive, very early, yet very evolved-looking galaxies. However, it’s only at relatively late cosmic times, from about ~550 million years onward, that practically every galaxy starts possessing large amounts of dust; prior to that, the dust fraction is variable, with some galaxies having plenty of dust already but others, particularly among the faintest galaxies, displaying little evidence for dust.

Credit: C. Jacobs, K. Glazebrook et al., arXiv:2208.06516, 2022

Above, you can see a selection of early galaxies imaged by JWST: galaxies whose light was emitted billions of years ago, in a Universe where only 13.8 billion years have elapsed since the earliest moments of the hot Big Bang. At the greatest cosmic distances of all, JWST can take us back more than 13.5 billion years in cosmic history, to an epoch when the Universe was just 2% of its current age. This is very exciting, and not just for the obvious reason that “we’re seeing farther back in cosmic history, and closer to the Big Bang, than ever before.”

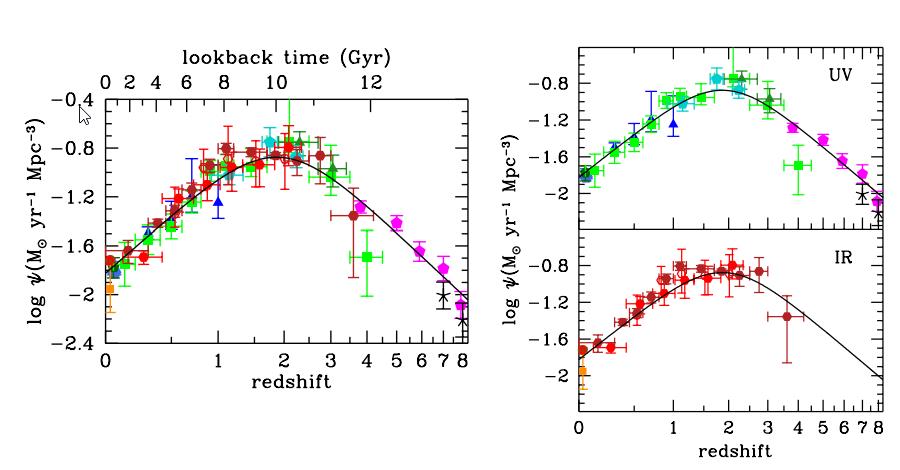

That’s because, over the course of the history of the Universe, stars didn’t form at a consistent rate, nor did they form all at once. Instead, our cosmic star-formation history started off as a trickle: where stars did indeed form during the first few hundred million years of cosmic history, but represent far less than 1% of the stars cumulatively formed from the Big Bang until now. Over time, the star-formation rate rose and rose, until it reached a peak — known as cosmic noon — that occurred about 3 billion years after the Big Bang. That peak was sustained for a couple of billion years, but then began to fall off, and fell further and further and further, continuing to fall even today. At the present time, the star-formation rate is only 3% of what it was at cosmic noon.

The star-formation rate in the Universe is a function of redshift, which is itself a function of cosmic time. The overall rate, (left) is derived from both ultraviolet and infrared observations, and is remarkably consistent across time and space. Note that star formation, today, is only a few percent of what it was at its peak (between 3-5%), and that the majority of stars were formed in the first ~5 billion years of our cosmic history. Only about ~15% of all stars, at maximum, have formed over the past 4.6 billion years. Direct measures of star-formation are important, and the JWST era has brought with it exquisite measurements for the star-formation rate at the greatest of redshifts.

Credit: P. Madau & M. Dickinson, 2014, ARAA

If that’s what the star-formation history of the Universe is, then you’d expect something else would be exquisitely correlated with it: the formation of dust in the Universe as well. The Universe wasn’t born with any dust after the Big Bang; dust requires the existence of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, and following the Big Bang, more than 99.999999% of the atoms in the Universe, by mass, were hydrogen and helium, making the formation of dust all but impossible.

However, the Universe does indeed create heavy elements once the first stars begin forming. Nuclear fusion doesn’t just fuse hydrogen into helium, but helium into carbon, carbon into neon and oxygen, and still heavier elements (silicon, sulfur, iron, etc.) beyond those. Once those heavy elements have come into existence, there are a variety mechanisms by which the Universe creates cosmic dust, including:

- from outflows arising from young, massive stars,

- within protoplanetary disks and even in halos surrounding young protostars,

- from stars, nearing the end of their lives, that reach the asymptotic giant branch stage,

- and in stellar deaths and cataclysms such as supernovae and planetary nebulae.

This image shows a variety of model simulations for how Herbig-Haro 30 (HH30) should appear in a variety of wavelengths of light, compared with the actual data at bottoms. As you can see, a variety of dust-particle sizes are needed to reproduce what’s observed, with lower dust masses and a fainter central protostar offering the best matches to the data.

Credit: R. Tazaki et al., Astrophysical Journal, 2025

Unfortunately, direct observations of dust are extremely difficult to conduct unless an object is relatively close by: in our cosmic vicinity. Sure, there’s often dust in the plane of a disk-like galaxy (such as a spiral galaxy), but that dust is usually only apparent when you can resolve the different components of the galaxy at high resolution. This is made more difficult, especially in the early Universe, by the fact that cosmic dust is normally confined, where it shows up in significant abundances, to very dense regions that are typically on the scale of an individual stellar system, rather than being extended over an entire galaxy.

So what chance do we have to trace the origin of cosmic dust, and to answer the question of, “where did this cosmic dust come from so early on in cosmic history, back before most of the Universe’s stars had an opportunity to form?”

You can tell if a galaxy has copious amounts of dust in it indirectly, even if the galaxy is far away and not well-resolved, by looking at the signatures within that galaxy of light absorption. Because dust is made of grains of a finite size, dust is transparent to long wavelengths of light (those with wavelength significantly longer than the physical sizes of the dust grains), absorbs short wavelengths of light (with shorter wavelengths than the dust grain’s sizes), and partially absorbs light of intermediate wavelengths. With spectroscopic measurements, we can do even better at pinpointing the abundance of dust. Using those techniques, we’ve probed many of the earliest galaxies in the Universe, including those found with JWST, for their dust contents, and have learned many valuable lessons from doing so, including about the existence of GELDAs: Galaxies with spectroscopically-derived Extremely Low Dust Attenuation.

This plot shows galaxies from the first ~1.5 billion years of cosmic history, color-coded by redshift and plotted by their metallicity (x-axis) as a function of the dust-to-stellar mass ratios (y-axis) found within them. The majority of low-metallicity galaxies are also dust-poor and are known as GELDAs, dominating the very early Universe, while later-time, more dust-rich galaxies are much more enriched in heavy elements.

Credit: D. Burgarella et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics accepted/arXiv:2504.13118v2, 2025

But even with these discoveries, the “origin of dust” puzzle persists. Among the earliest galaxies, those coming from the first 550 million years of cosmic history, an impressive 17% of them still have large amounts of dust. From the next ~1 billion years of cosmic history, 74% of them are rich in dust. And after that, nearly all galaxies show strong evidence for the abundant presence of dust. Moreover, although there’s a correlation between the abundance of heavy elements (what astronomers call metallicity) in a galaxy with the amount of dust that’s present in that same galaxy, the correlation isn’t 1-to-1: there are plenty of low-metallicity galaxies, even from very early on in cosmic history, that still possess large quantities of dust.

So why is that, and where did that dust come from?

In order to answer that directly, we’d have to look at those early galaxies up close, in high-resolution, to see where the dust both:

- is being generated within them,

- and is displaying the strongest signatures of existence.

Of course, even with the greatest observatories we have today, including Hubble, JWST, ALMA, and the large suite of ground based optical, infrared, and radio observatories at humanity’s disposal, the vast distances to these small, faint, infant galaxies is too much of a barrier even for our impressive arsenal of astronomical tools. However, there is another way to get an answer — albeit a more indirect answer — by looking at galaxies that can be found nearby, except with similar properties to these ultra-distant, low-metallicity, dust-plentiful galaxies.

This multi-panel diagram shows the isolated, low-mass dwarf galaxy Sextans A, including a portion of the star-forming region imaged by JWST, with a particular set of clumps corresponding to particularly complex, dust-rich regions highlighted by JWST.

Credit: E.J. Tarantino et al., arXiv:2512.04060, 2025

That’s what a team led by Dr. Elizabeth Tarantino did with JWST, by choosing to look at the nearby dwarf galaxy Sextans A. Sextans A, as you can see above, is a very interesting object that’s right on the edge of our Local Group: located about 4.6 million light-years away. Sextans A is located far away not just from the Milky Way, but from Andromeda, Triangulum, Bode’s galaxy, and all other large galaxies in our vicinity. In other words, it’s an extremely isolated galaxy, a low-mass galaxy, and an extremely metal-poor galaxy all in one: a galaxy that, in many ways, resembles the early, primitive galaxies from the early Universe. The full extent of Sextans A, in particular, is shown in panel “A” above.

The highlighted region in panel A was imaged by JWST as part of this latest research work, and is shown in the large panel B. In particular, many different JWST filters were used, so — for example — the region within the green box in panel B can be highlighted in filters from between 3.0 and 3.6 microns (C), between 5.6 and 10.0 microns (D), or between 10 and 15 microns (E), revealing the same region of space in different wavelengths of light. The shorter wavelengths of light largely are good at highlighting stars, particularly the presence of evolved red giant stars, which appear abundantly in panel C but not in panels D or E. The longer wavelengths of light, however, at much better at highlighting much cooler clumps of heated gas and dust, typically at below-freezing temperatures.

There are, however, some regions that appear bright in all three panels, such as the region in the highlighted white, dotted circle. And those features correspond to something very special: a population of a specific type of molecule known as a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon.

Graphene, in its ideal configuration, is a defect-free network of carbon atoms bound into a perfectly hexagonal arrangement. It can be viewed as an infinite array of aromatic molecules. For a finite array, some of those carbon atoms will be bound to hydrogen atoms, resulting in an aromatic hydrocarbon instead.

Credit: AlexanderAIUS/Core-Materials/flickr

The name polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon might sound complicated, but it’s relatively straightforward. Hydrogen is the most common and abundant element in the Universe, and carbon is the first heavy element you make once stars first begin to form. While hydrogen and helium persist as the two most common species of atom to exist in the Universe, carbon is pretty common too, coming in at number four, with only oxygen reaching a greater abundance in the number 3 spot. When carbon and hydrogen atoms bind together, in any configuration, to make a molecule, that molecule is known as a hydrocarbon.

There are plenty of molecules that exist, chemically, that are composed of carbon and hydrogen in ringed configurations — such as benzene — where the various carbon atoms are linked together in rings of six carbon atoms apiece; the geometry of carbon bonding supports these bond angles as a more stable configuration over configurations with either greater or fewer numbers of carbon atoms. Wherever the ringed configuration exists, we call that an aromatic molecule. So that explains the “aromatic hydrocarbon” part, and then instead of single-ringed molecules, many aromatic species actually have multiple “carbon ring” configurations linked up together. That’s what makes a molecule polycyclic, and hence that’s what a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon is. Whereas “heated dust” emits across a wide variety of infrared wavelengths, in a temperature-dependent fashion, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are excited by a few specific wavelengths: at 3.3, 7.7, and 11.3 microns.

This four-panel image is specifically focused on wavelengths of 3.3 microns, 7.7 microns, and 11.3 microns: wavelengths at which polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules exhibit the strongest emission signatures when heated by an external source.

Credit: E.J. Tarantino et al., arXiv:2512.04060, 2025

Whereas, above, the regions that appear in the 15 micron window (panel D) correspond to general thermal emission, the regions that are also excessively bright in those three polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon wavelength windows correspond not only to those molecules, but to a substantial density of those molecules in a region where they’re being heated — and thus, from a molecule’s point of view, excited into a state where they can copiously emit energy — by an external source.

Now, even at “just” a distance of 4.6 million light-years away, none of the telescopes we have in our arsenal are capable of resolving what that external source is, but we have a comprehensive enough knowledge of astrophysics to know what’s going on: these are young protostars, or clumps of matter in the process of giving birth to new stars, that are heating up and exciting the molecules that are present surrounding them. We see these up close here in our own Milky Way, often in great detail, but when we see them from far away, all they look like is small, shielded clumps of glowing dust that appear bright at these three specific wavelengths: 3.3, 7.7, and 11.3 microns.

So even though this galaxy is an extremely low-metallicity galaxy, with only about 3% of the amount of heavy elements (oxygen, carbon, neon, iron, etc.) found in our Solar System, we can be certain that it has plenty of dust inside of it. That’s big news. But these protostars, or young stellar objects (YSOs) as they’re sometimes called, aren’t sites of dust production; they’re just the sites where you can observe the dust’s presence. So where is it getting created?

The dying red giant star, R Sculptoris, exhibits a very unusual set of ejecta when viewed in millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths: revealing a spiral structure. This is thought to be due to the presence of a binary companion: something our own Sun lacks but that approximately half of the stars in the universe possess. Stars lose approximately half of their mass — some more, and some less — as they evolve through the red giant and AGB phases and into an eventual planetary nebula/white dwarf combination.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M. Maercker et al.

Again, we know the answer from looking nearby: a very large producer of cosmic dust are stars like R Sculptoris, shown above, which is known as an AGB star, or a star on the asymptotic giant branch of stellar evolution. During this phase — one of the final phases in the lives of all but the absolutely most massive stars — an extraordinarily large amount of dust can be produced. In fact, for every “solar mass” worth of stars that enters the AGB phase, a few percent of that mass can be converted into dust, which is a remarkably significant amount of dust by any metric.

While the aforementioned young stellar objects may be glowing copiously with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules, they aren’t the sites from which the dust was produced; they’re merely the locations from which the dust can be detected from its characteristic glow, proving it ubiquitously exists. But separately, independent of those glowing protostars, we can not only identify and look at where the AGB stars within Sextans A are, we can also take a spectrum of those AGB stars, and determine what the properties and composition of the dust are that is actively being produced by those AGB stars within Sextans A.

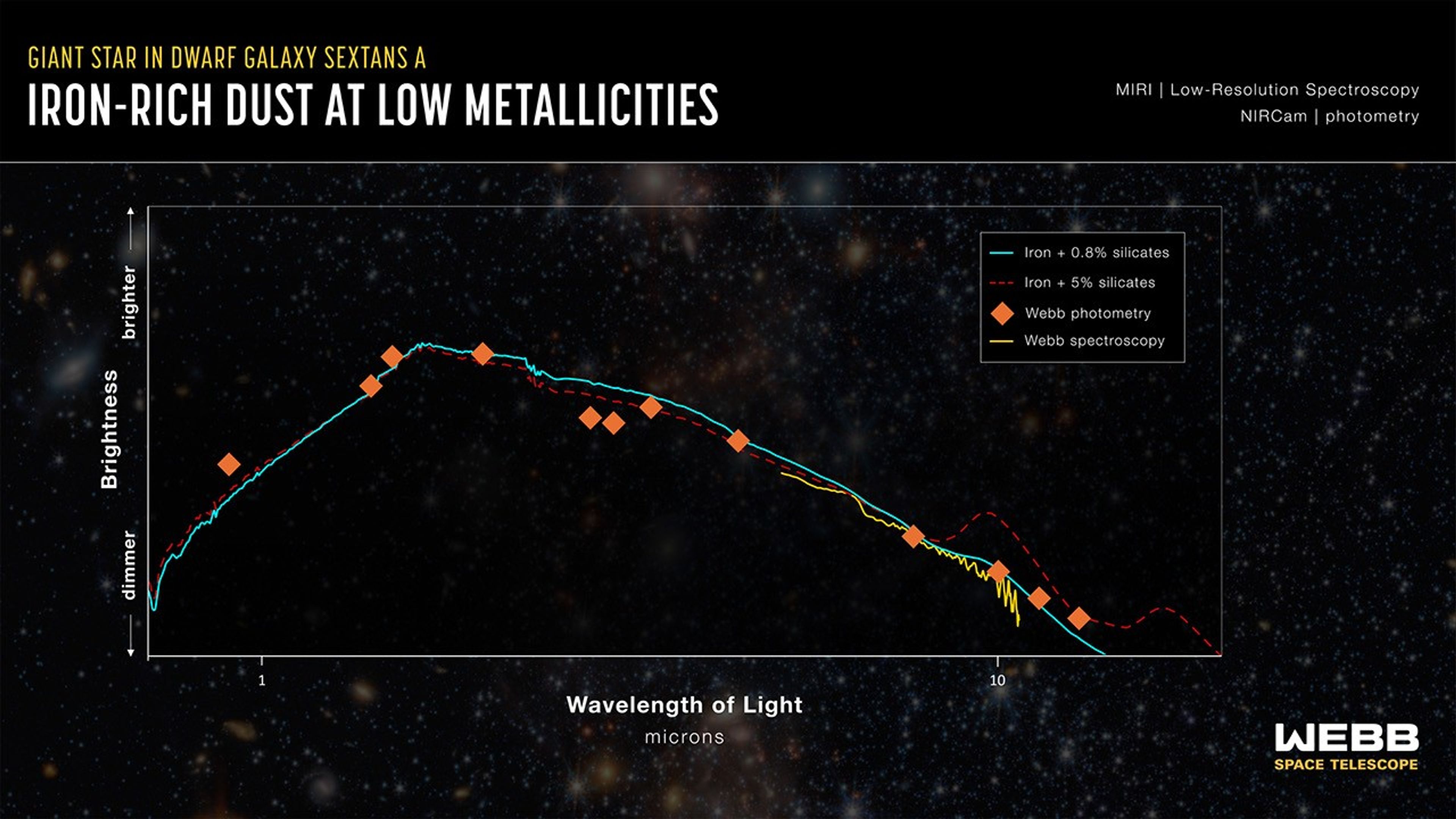

AGB stars have existed all throughout cosmic history, and are expected to play a major role in cosmic dust production for as long as stars have existed. What’s fascinating, however, is that the total fraction of heavy elements that exist within the AGB star itself lead to a relationship between what the specific element ratios of the dust that it produces turns out to be. In particular, a low fraction of heavy elements leads to iron-rich but silicon-poor dust production, while greater fractions would lead to a significant silicon presence as well, as a recent companion study has demonstrated.

This graph shows a spectrum of an Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) star in the Sextans A galaxy. It compares data collected by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope with models of mostly silicate-free dust and dust containing at least 5% silicates. Note that a silicon-free spectrum and a spectrum that includes silicon at the 0.8% abundance level cannot be distinguished by the current data, but a 5% silicon contribution can be ruled out.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

This is remarkable, because here in the modern Milky Way, a mix of three key ingredients are required to make dust: carbon, silicon, and iron. But back in the early Universe, not all of those ingredient are abundant, and so it was a bit puzzling as to whether dust could be produced at all by the conventionally understood mechanisms. The Sextans A observations, definitively, put any doubts to rest: even with barely any silicon at all, dust is still getting generated, even if AGB stars are hardly producing any silicon at all. It’s like learning you can bake a cake without flour, and that under the right conditions, simply using butter and sugar will do.

While today’s dust that we observe up close might be predominantly composed of silicate grains, dust in the early Universe, although different from today’s dust, can still be brought into existence. With the power of JWST and a mix of complex theoretical modeling and clever observational techniques, we’ve just revealed how it happens in Sextans A, which lacks many of the evolved property that our own Milky Way possesses, but which closely mirrors what should have happened early on in cosmic history: back when we’re seeing the dusty JWST galaxies that have relatively small fractions of heavy elements within them. At long last, after decades of wondering how the most distant galaxies of all could possibly produce dust at such early times, we’ve finally learned that “too much, too soon,” is the wrong question to be asking. Apparently, the recipe our own galaxy uses wasn’t the recipe the Universe followed back in its more pristine past!

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.