Tropical upwelling zones are often overshadowed by their higher-latitude counterparts in ocean science, yet they play an outsized role in maintaining global marine productivity. These systems help fertilise surface waters, sustain fisheries, and regulate coastal temperatures. Their seasonal reliability is critical, especially in the eastern tropical Pacific, where ocean-atmosphere interactions are tightly coupled with regional ecosystems.

The Gulf of Panama is one such zone. Each year, between January and April, a recurring surge of trade winds sets off a natural chain reaction: warm surface water is pushed offshore, and cool, nutrient-rich water rises from the depths to take its place. The result is a short but intense pulse of biological activity that supports the region’s fisheries and coral reefs.

Scientists have long monitored this process, both for its ecological importance and its sensitivity to broader climate dynamics. The upwelling in Panama has weathered El Niño and La Niña cycles, adapting in timing and intensity but maintaining its annual rhythm.

In 2025, that pattern broke. For the first time in over four decades of observation, the Panama upwelling failed to occur. The implications of this absence are now the subject of close scientific scrutiny.

First Recorded Failure in Over 40 Years

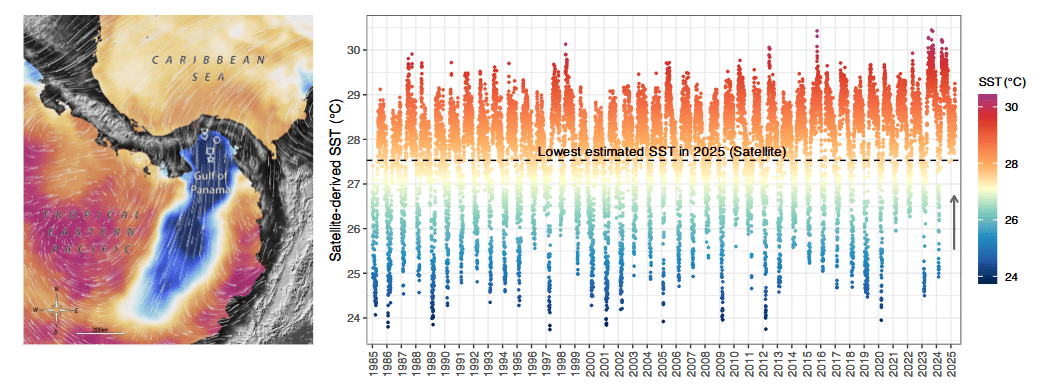

The event was detailed in a peer-reviewed study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, led by researchers from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, and several international partners. Their analysis used satellite observations, sea surface temperature records, and direct field measurements to reconstruct the seasonal cycle in early 2025.

Data showed that the usual upwelling in the eastern Pacific off Panama did not occur. Surface waters remained unusually warm and lacked the typical chlorophyll signals associated with phytoplankton blooms. Researchers aboard the research vessel Eugen Seibold found no evidence of vertical mixing, with cooler, oxygen-rich waters trapped below a stratified surface layer.

A) Typical upwelling and study sites. B) Satellite-derived sea surface temperatures (1985-2025). Credit: Andres Ordonez

A) Typical upwelling and study sites. B) Satellite-derived sea surface temperatures (1985-2025). Credit: Andres Ordonez

The anomaly marked a break from all previous data extending back to 1985. Even in years affected by strong ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) conditions, the upwelling had not fully stalled. This was the first complete absence on record.

For a detailed satellite-based chronology of this collapse, NASA Earth Observations offers long-term datasets on sea surface temperature and chlorophyll that corroborate these findings.

Wind Frequency, Not Intensity, Identified as the Trigger

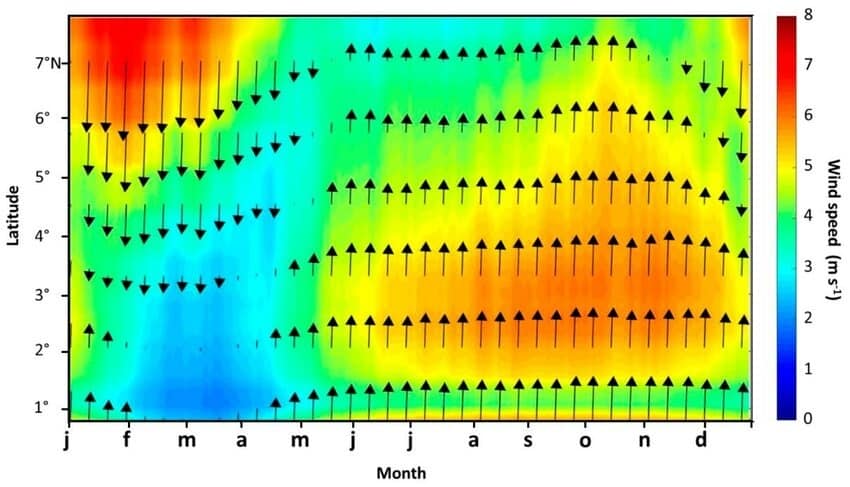

The study traced the failure to a sharp drop in the frequency of short-lived wind bursts known as Panama wind jets, a component of the Panama Low-Level Jet (PLLJ). These wind events, occurring during the dry season, typically drive surface waters offshore, initiating the upwelling cycle.

In 2025, the number of wind jet events decreased by approximately 74 percent relative to historical patterns. Importantly, the wind speeds themselves remained near normal when they did occur. It was the lack of regular events, rather than weaker winds, that disrupted the system.

This drop in frequency was linked to a northward shift in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a persistent atmospheric feature influencing tropical wind patterns. That shift coincided with a La Niña event in late 2024 and early 2025, but researchers noted that stronger La Niña phases in the past had not caused similar collapses.

Annual cycle of the Panama Low-Level Jet (PLLJ) winds speeds calculated at PLLJmax. The arrows indicate the wind magnitude and direction at 10 m from the surface. IFREMER-CERSAT data 1992-2018. Credit: Andres Ordonez

Annual cycle of the Panama Low-Level Jet (PLLJ) winds speeds calculated at PLLJmax. The arrows indicate the wind magnitude and direction at 10 m from the surface. IFREMER-CERSAT data 1992-2018. Credit: Andres Ordonez

Long-term variability in tropical winds has been a growing focus in climate science. As highlighted in NOAA’s ENSO blog, such shifts in the ITCZ can have far-reaching effects on regional atmospheric circulation and ocean processes.

The findings suggest that baseline atmospheric conditions may be changing in ways that affect the consistency of wind-ocean interactions. “Tropical upwelling systems may be more vulnerable than previously believed,” the authors wrote in PNAS.

Disruption Impacts Regional Ecosystems and Fisheries

The biological impacts of the upwelling failure appeared quickly. Phytoplankton, which rely on nutrients brought up from the deep, declined significantly. This drop affected the food chain at multiple levels. Fish species such as sardines, mackerel, and other pelagics experienced population declines along the Panamanian coast. These species form the basis of regional fisheries, both for local subsistence and for commercial trade.

Coral reef ecosystems also suffered. Without the usual seasonal cooling, reef structures were exposed to prolonged thermal stress. In early 2025, bleaching events intensified and became more widespread. In parallel, oxygen levels in the water column decreased, creating additional stress for bottom-dwelling marine life.

Coral nearby Island in San Blas, Panama. Credit: Shutterstock

Coral nearby Island in San Blas, Panama. Credit: Shutterstock

For more on the ecological consequences of coral heat exposure, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch provides global monitoring tools and temperature anomaly reports that align with the Panama findings.

These outcomes underscore the close coupling between physical ocean processes and marine ecosystem health, particularly in tropical zones where short-term variability can have long-term effects.

Gaps in Monitoring Hinder Early Detection

The collapse may have gone unnoticed had it not been for sustained ocean monitoring efforts. Compared with temperate regions, tropical upwelling systems remain under-observed. The Gulf of Panama, in particular, lacks the dense sensor networks and institutional focus found in places such as the California Current or Humboldt Current systems.

This gap in coverage carries broader implications. Tropical upwelling zones contribute significantly to global carbon cycling, fisheries production, and climate regulation, yet they are underrepresented in global models. Without comprehensive data, early warning signals of systemic change can be missed.

A 2023 United Nations Ocean Decade policy brief emphasised the need to expand observing networks in equatorial regions, calling tropical systems “blind spots” in both research and forecasting capacity.

The study’s authors recommend greater investment in observational infrastructure and improvements in how wind-ocean dynamics are represented in climate models. “The future stability of entire marine ecosystems may depend on it,” the paper concludes.