The feat was made possible by XRISM’s high-resolution “Resolve” instrument, working in tandem with ESA’s XMM-Newton and NASA’s NuSTAR. Together, these observatories isolated the warped X-ray signatures of iron close to the black hole’s event horizon, confirming relativistic effects that Einstein’s theory predicted, but that telescopes until now had struggled to fully resolve.

Launched in September 2023, XRISM (X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) was designed specifically to map high-energy phenomena in space with a level of clarity unattainable before. This latest study focused on MCG–6-30-15, a Type 1 Seyfert galaxy located 120.7 million light-years away, long known for its unusually distorted X-ray emissions. At the center lies a supermassive black hole (SMBH) estimated to be 2 million times the mass of our Sun.

What makes the result particularly striking is the telescope’s ability to separate different X-ray sources. Until now, most instruments blended emissions from the inner disk near the event horizon with those from gas clouds further out. That limitation has now been broken.

Clearest X-Ray Signature of Relativistic Reflection to Date

For decades, researchers have debated whether the warped iron emissions in MCG–6-30-15 stemmed from material falling toward the black hole or from outflowing winds further away. According to the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, the XRISM team, led by astrophysicist Laura Brenneman, resolved this question by capturing a distinct, broad iron emission line produced just outside the black hole’s event horizon.

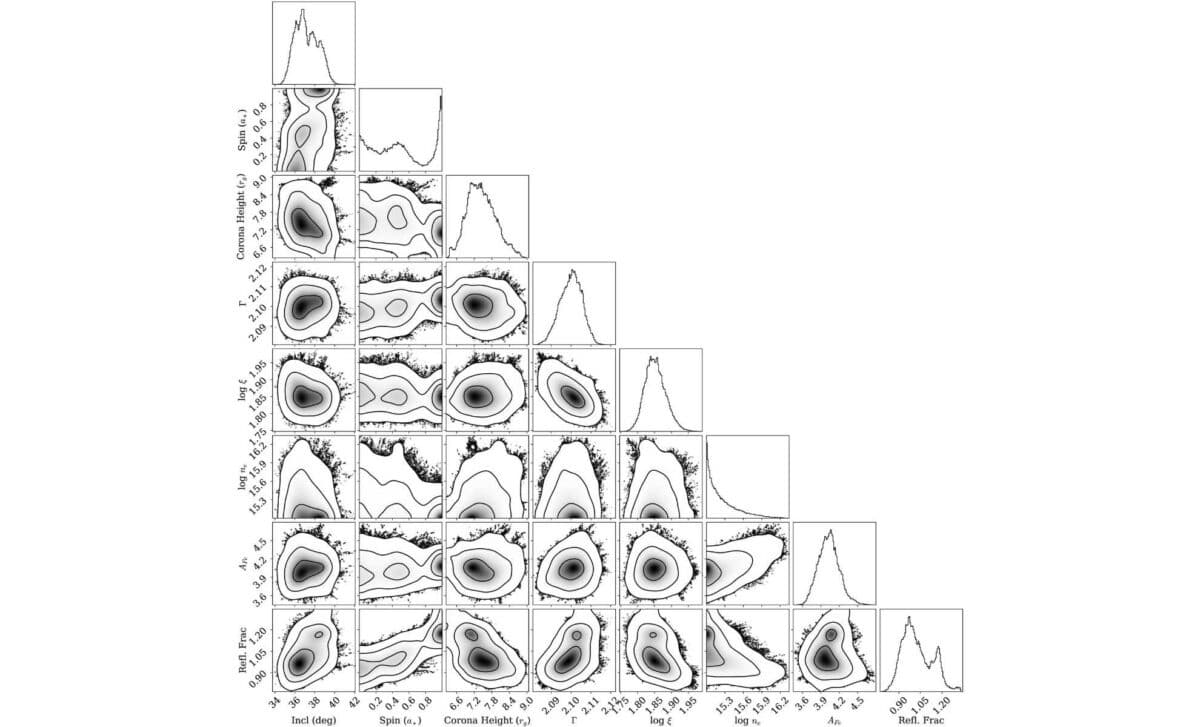

Thanks to XRISM’s <5 eV resolution, scientists were able to model not only the reflection of X-rays off the inner accretion disk but also distinguish between narrow and broad components that were previously blended together. According to the research, the detection of the broadened iron line in the X-ray spectrum is consistent with relativistic reflection occurring near the event horizon.

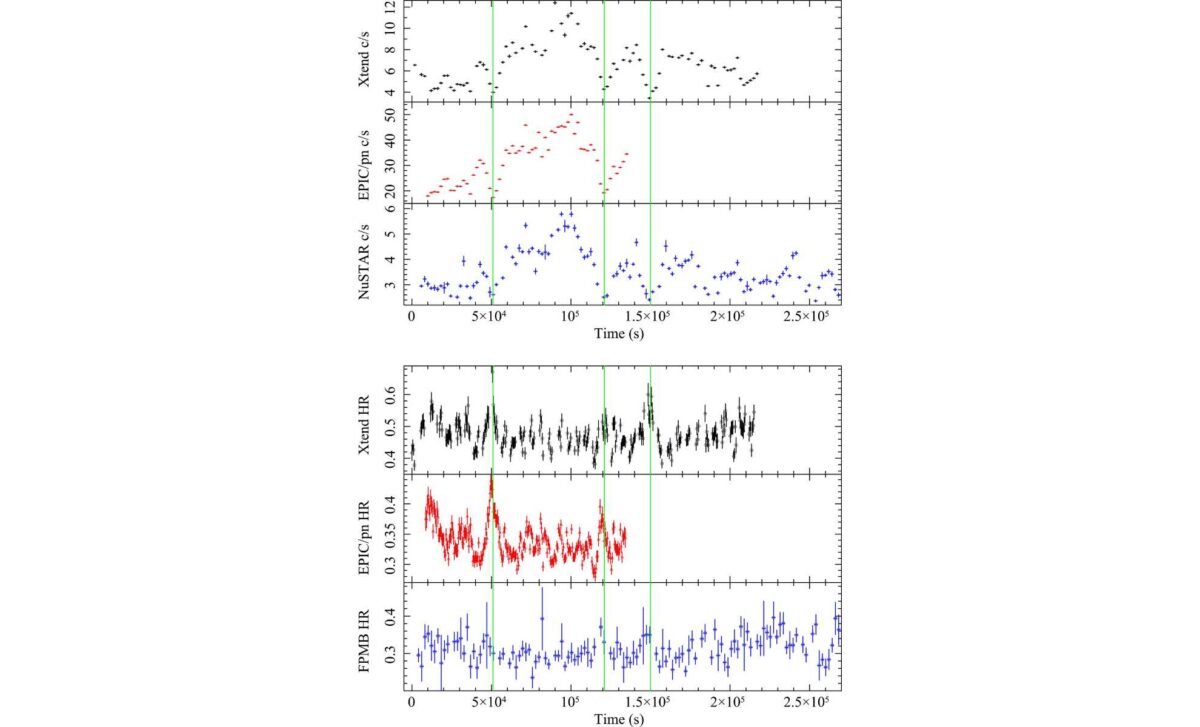

The study found that the inner disk’s reflected X-ray signature was over 50 times stronger than the reflection produced by more distant gas. The black hole’s spin, an elusive property that can only be measured through high-resolution data, was also constrained. While previous studies using lower-resolution instruments suggested high spin, the new data revealed a more complex picture: time-averaged analysis pointed to a value of a ≥ 0.65, indicating rapid prograde rotation but with a less precise constraint than expected. This uncertainty was linked to the variability in the black hole’s emission during the observation campaign.

Five Distinct Wind Zones Identified Around the Black Hole

Beyond the spectral clarity of the Fe Kα line, the XRISM mission also detected at least five separate zones of outflowing wind. These included one dusty component and four highly ionized gas components, moving at velocities of up to 20,000 km/s, according to data published in The Astrophysical Journal.

This discovery suggests the presence of a multi-layered wind structure, a phenomenon that plays a key role in regulating galaxy growth. The absorption features tied to these winds were clearly visible in the Fe K band, where XRISM successfully disentangled them from the broader reflection signals.

Earlier instruments, such as Chandra’s High Energy Transmission Grating (HETG), hinted at the presence of such features but lacked the sensitivity above 7 keV to confirm them. XRISM not only verified the previously known 2,300 km/s component but also revealed a faster, more powerful outflow that had remained hidden until now.

These findings help clarify the complex relationship between SMBHs and their host galaxies. According to Brenneman, understanding both the spin and wind structure allows astronomers to better track how black holes feed and evolve over time.

The Missing Reflection From the Distant Torus

One of the unexpected outcomes of the study was the relative weakness of the distant reflection component. While the narrow Fe Kα line at 6.4 keV was clearly detected, the associated Compton hump, usually a key feature of distant, cold reflection, was largely absent. Models predicted a much stronger signal from the torus-like structure thought to surround the black hole, but the data did not support that.

This discrepancy led the team to test alternative models. The best-fitting explanation suggests that the distant reflector may be nonuniform or chemically enriched, with iron abundances possibly exceeding four times the solar value. XRISM’s data showed that standard models assuming solar metallicity could not reproduce the observed spectral profile.

Attempts to fit the data with an absorption-dominated model, where outflows alone would mimic the Fe Kα features, also failed. According to Brenneman’s team, removing the inner disk reflection from the model resulted in a dramatic worsening of the statistical fit, further reinforcing that the observed broad line must come from relativistic reflection near the event horizon.

Despite this, the source’s spectral variability added complexity. The five-day observing campaign showed flux changes by a factor of three, altering the spectral shape on timescales as short as 2,000 seconds. This variability will be addressed in future, time-resolved analyses.

The XRISM mission has confirmed the presence of relativistic effects in the X-ray spectrum of MCG–6-30-15 with unprecedented precision. The detection of multiple wind layers and the clean separation of broad and narrow features mark a major step forward in black hole astrophysics. And while many questions remain, such as the true nature of the distant reflector, the data collected by XRISM, XMM-Newton, and NuSTAR will serve as a foundation for years of investigation to come.