They just needed a spark.

The American colonies in the autumn of 1775, then under the thumb of King George III and his sprawling British Empire, were divided on the prospect of independence.

Revolutionary ideas start in refined quarters, but they must spread to the masses to surge into action.

And the 13 colonies were divided in threes: those who favored independence from English rule, those who opposed it, and those who wished to remain neutral.

And then the spark arrived as a pamphlet.

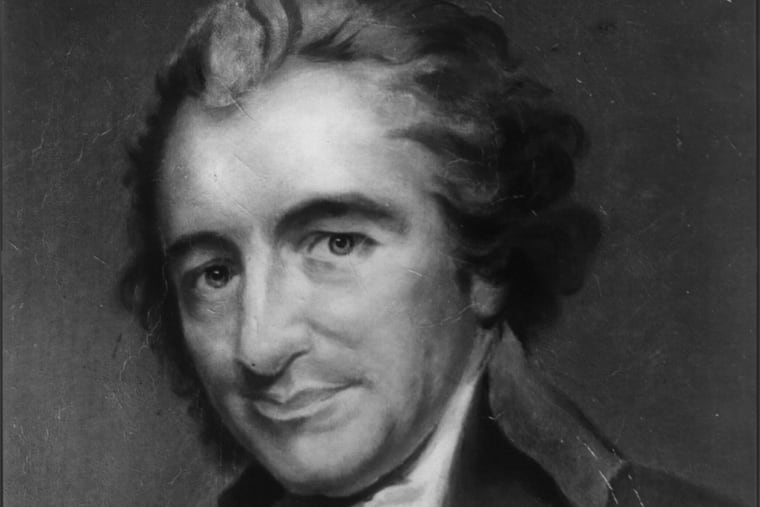

On Jan. 10, 1776, in a small publishing house at Third and Walnut Streets in present-day Old City, Englishman Thomas Paine published his 47-page document. It promoted the cause of American independence, and stoked the fires of revolution.

This pamphlet, titled “Common Sense,” was first printed anonymously.

But the colonists knew who wrote it.

Paine was a self-educated rabble-rouser who had found little success making corsets or collecting taxes.

And who, upon meeting Benjamin Franklin after giving a speech in London, opted to join the upstart colonists and move to America in 1774.

After following Franklin to Philadelphia, he followed him into journalism, writing and editing for Pennsylvania Magazine.

It’s where he displayed a knack for speaking to the common people through essays denouncing slavery, promoting women’s rights, and dumping on English rule.

And again he took from Franklin, turning his pamphlet into a lightning rod.

In it he laid out his arguments in plain language.

An island, he argued, should not rule a continent.

“Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation,” he wrote.

More than 500,000 copies circulated the colonies, convincing the commoners, the people who would actually take up arms against the Royal military, to support a war against Great Britain.

Despite his outsized role in lighting the fires of rebellion, Paine’s services would go unrecognized for a generation.

He temporarily returned to Europe after the war, and his later denouncing of Christianity did him no favors on either side of the Atlantic. He died in poverty in New York in 1809 at age 72.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-1970s for historians to recognize the enduring power of Paine’s pamphlet, which now holds a place of honor a step below Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.