Talk about the souvenir from hell. A recent case report documents how a woman’s overseas trip to South America left her playing host to a worm parasite stuck in her eye.

Researchers in Chile and elsewhere detailed the eye-opening case last month in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. The 26-year-old UK resident developed a severe bout of conjunctivitis the scientists traced back to a wriggling adult Philophthalmus lacrymosus fluke—one she probably caught weeks earlier while visiting the Galápagos Islands off Ecuador. Though the worm was safely pulled out of the woman’s eye with no issue, more people in the area could be vulnerable to these infestations, the researchers say.

“Our clinical and epidemiologic findings show that the zoonotic eye fluke P. lacrymosus can infect humans in South America. The findings also suggest that the parasite might be endemic on the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador,” they wrote.

A fluke case

According to the report, the woman visited doctors in Santiago, Chile, nine days into having intense pain, swelling, and the sensation of feeling something moving in her right eye.

After a thorough examination, the doctors spotted an “elongated mobile structure” in the conjunctiva of her eye (the thin, clear membrane that protects the eye). They then removed the foreign object by using a moist cotton swab, which relieved the unpleasant eye sensation. In the weeks after, she made a complete recovery with no complications.

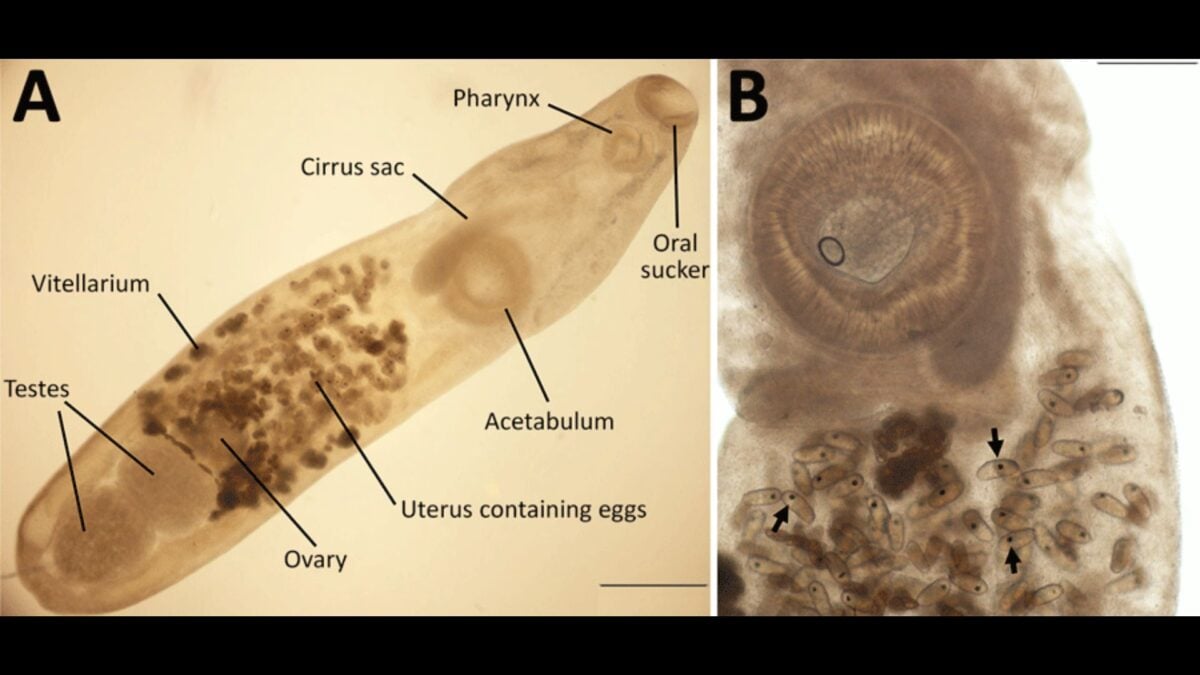

The authors placed the eye intruder under a microscope and determined it was a P. lacrymosus fluke, which they further confirmed through genetic testing.

Flukes are a class of parasitic flatworms formally known as trematodes. They have a complex life cycle that involves multiple hosts, which can include people. In people, fluke infections are typically grouped by where in the body the worms invade, such as the blood or liver. Eye fluke infections are primarily caused by Philophthalmus worms like P. lacrymosus, but they’re only rarely reported. Since 1939, the researchers wrote, only 12 other cases of similar infections have been documented in the medical literature.

P. lacrymosus worms have been found in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Their final, definitive hosts (the hosts where they reach maturity and mate) are waterbirds, and their intermediate hosts are marine snails. Sometimes, however, the worms can infect other vertebrates like mammals.

A hidden endemic threat?

In this specific case, the woman reported visiting Chile, Ecuador, and Peru prior to her symptoms starting. But the only time she was in a natural water environment was when she visited the Galápagos Islands. So that’s the most likely place where she contracted the infection, the doctors say.

Exactly how it happened remains a mystery. Some case reports indicate that people can catch the infection through direct contact with larval cysts in the water while swimming, according to the researchers, yet others have linked infection to eating or handling food contaminated with the larva.

We know very little about these worms, including how many distinct species of Philophthalmus there are in the world. And interestingly enough, the worm found in the woman’s eye bears a close resemblance to a recently discovered species of fluke found in sea lions living near the Galápagos Islands called P. zalophi. So close, in fact, it’s possible that P. lacrymosus and P. zalophi are the exact same species, the researchers argue. Flukes are known to physically adapt to their mammalian hosts, they note, which could explain why scientists might have mistakenly identified the sea lion worms as a new species.

However many kinds of these worms there are, it seems likely that some call the Galápagos Islands home. So more research needs to be done to better understand the ecology and host range of these flukes, the researchers say. And while human infections do seem to be rare, people who experience eye trouble after traveling to potentially endemic regions should at least be aware of the possibility, as should the doctors treating them.

“The consequences for travelers and physicians attending them is that they should consider philophthalmiasis if people complain about a foreign body sensation during or after travel,” lead author Thomas Weitzel, a tropical medicine and parasitology expert at the Universidad del Desarrollo in Chile, told Gizmodo. “The treatment is the extraction of the worm which should be done by an ophthalmologist.”

Personally, I’m just thrilled to know there are even more awful things that can set up shop inside my juicy eyes if given the chance.

This article has been updated to include comments from the study’s lead author.