Black holes are objects so dense that they warp space time to an extreme degree. They may be better described as places than objects, but regardless, the point stands. So strong is their effect that not even light can esacpe their grasp.

The regions around black holes, and especially supermassive black holes (SMBH) like the one in the center of the Milky Way, are extreme environments. The gravity, radiation, and magnetic fields turn these regions into violently destructive arenas that at times emit brilliant light as active galactic nuclei (AGN). Astronomers can see these AGN flaring all across the Universe. But at other times these SMBH regions are relatively quiet.

The SMBH at the core of the Milky Way is known as a particulary quiet one. It’s name is Sagittarius A*. But, according to new research, in the recent past—a few hundred or a thousand years ago—it wasn’t.

The research is titled “Resolving the Fe Kα Doublet of the Galactic Center Molecular Cloud G0.11-0.11 with XRISM,” and will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The lead author is Stephen DiKerby, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State University. DiKerby also presented the results at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

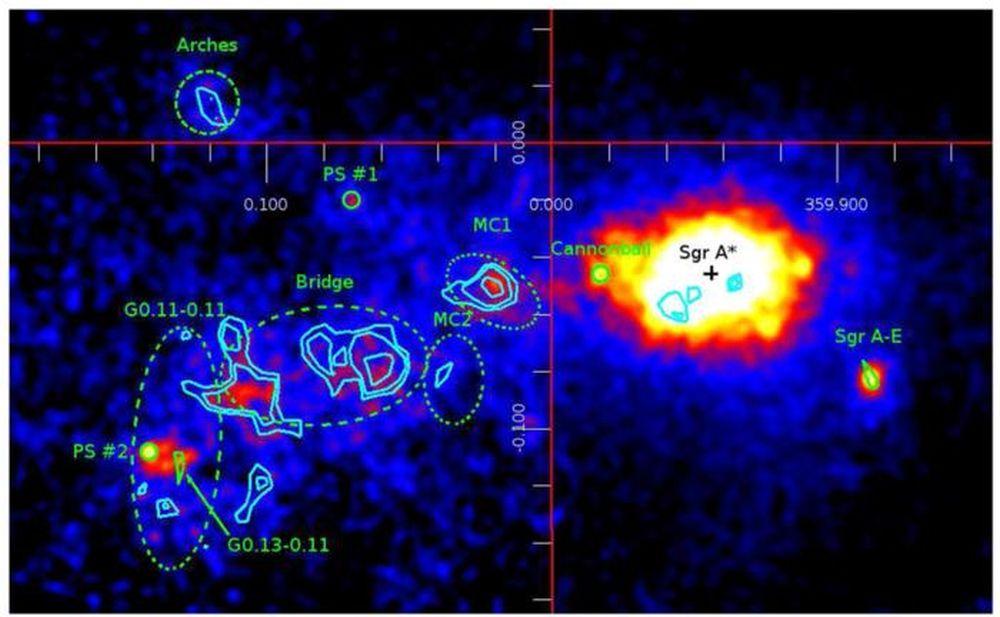

“When we look in towards the galactic center, we’re seeing the most crowded, chaotic environment in our galaxy,” DiKerby said in a press conference. “Hundreds of millions of stars are packed into the bulge of our galaxy, just a few hundred parsecs across. Besides all those stars, the galactic center also has a variety of exotic objects that are unique, studied in high-energy x-ray and gamma-ray light.” Some of those objects are molecular gas clouds.

Objects like gas clouds are drawn into the chaotic and high-energy environments around SMBH, and can linger for long periods of time before ever being pulled across the event horizon. One named G0.11-0.11 has captured the attention of astronomers. The gas clouds around the SMBH can reflect light from past active episodes as x-ray light, but it takes a powerful x-ray telescope to observe it. Up until now, telescopes weren’t capable of observing it in detail. But XRISM can.

*This is an infrared JWST image of a gas cloud in the center named Sagittarius B2. It’s very similar to the gas cloud in this research, G0.11-0.11, for which there is no JWST image. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Ginsburg (University of Florida), N. Budaiev (University of Florida), T. Yoo (University of Florida). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI); CC BY 4.0*

*This is an infrared JWST image of a gas cloud in the center named Sagittarius B2. It’s very similar to the gas cloud in this research, G0.11-0.11, for which there is no JWST image. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Ginsburg (University of Florida), N. Budaiev (University of Florida), T. Yoo (University of Florida). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI); CC BY 4.0*

In this work, the researchers used the XRISM x-ray astronomy space telescope to observe the cloud. XRISM is able to observe x-ray sources in great detail, by resolving the energy level of individual photons. The observations are centered on what’s called the Fe Kα emission line complex, where Fe is iron, and the Kα line is when an atom is ionized and releases an x-ray photon. In this context, the atom in question is iron.

The Fe Kα line is only one of several characteristic lines in astronomy, but is usually the strongest and most easily observed. It’s especially important in observations of things like black holes and neutron stars, and, in this case, the gas cloud G0.11-0.11. In their paper, the authors describe it as “one of the most potent emission lines studied in Xray astronomy.”

“We can use it to explore the history of Sagittarius A-star, how it’s gotten brighter and dimmer over the past thousand years,” DiKerby said at the conference.

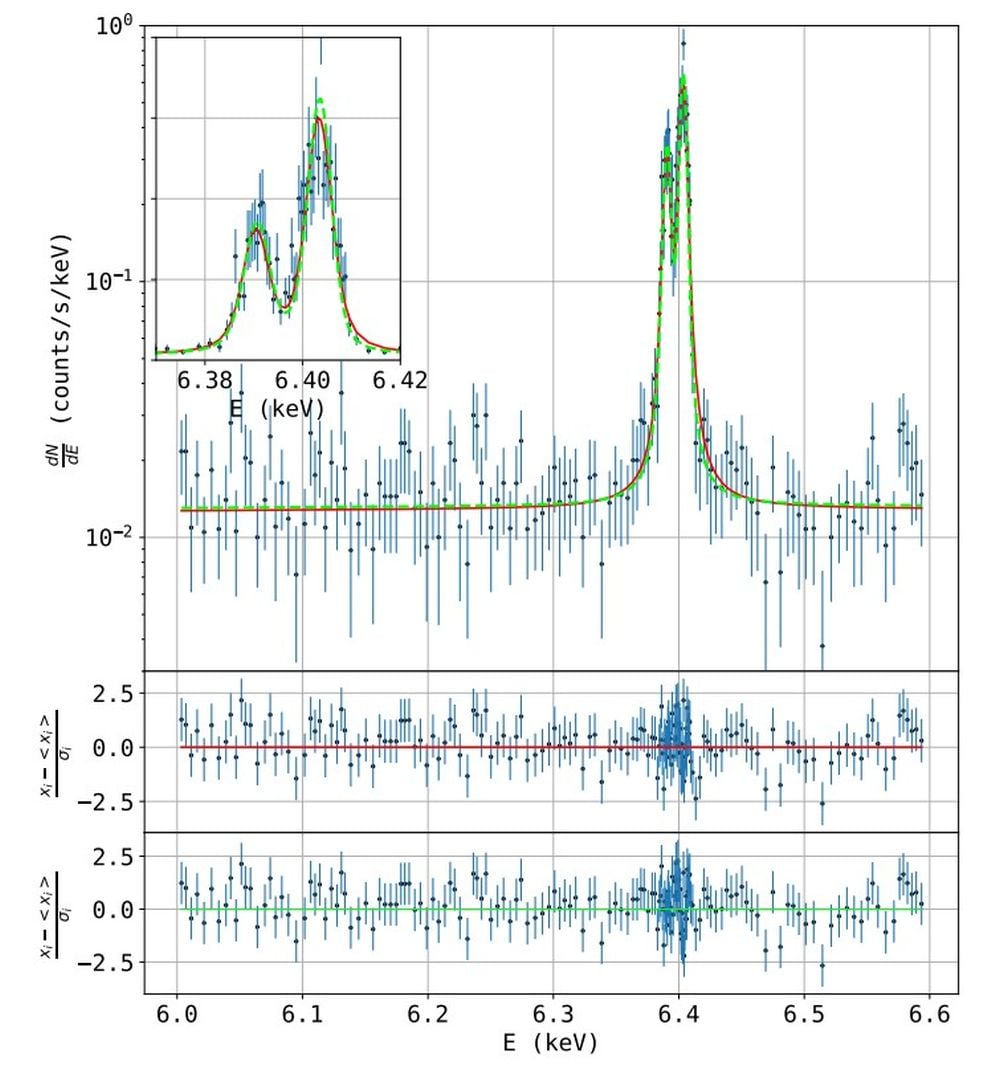

This graph shows the Fe Kα doublet in the x-ray spectrum from the cloud G0.11-0.11 (inset). The bottom two rows shows the data fitted to two different, detailed models of x-ray emissions. This is what astronomy looks like behind the headlines. Image Credit: DiKerby et al. 2025.

This graph shows the Fe Kα doublet in the x-ray spectrum from the cloud G0.11-0.11 (inset). The bottom two rows shows the data fitted to two different, detailed models of x-ray emissions. This is what astronomy looks like behind the headlines. Image Credit: DiKerby et al. 2025.

The researchers point out that there are two ways this line can be emitted from the cloud.

“Fe Kα line emission from Galactic center molecular clouds can be produced either via fluorescence after illumination by an X-ray source or by cosmic ray ionization,” the authors write in their research. “Unparalleled high-resolution X-ray spectroscopy obtained by XRISM/Resolve for the galactic center molecular cloud G0.11-0.11 resolves

its Fe Kα line complex for the first time, and points to a new method for discrimination between the X-ray reflection and cosmic ray ionization models.”

“Nothing in my professional training as an X-ray astronomer had prepared me for something like this,” said lead author DiKerby in a press release. “This is an exciting new capability and a brand-new toolbox for developing these techniques.”

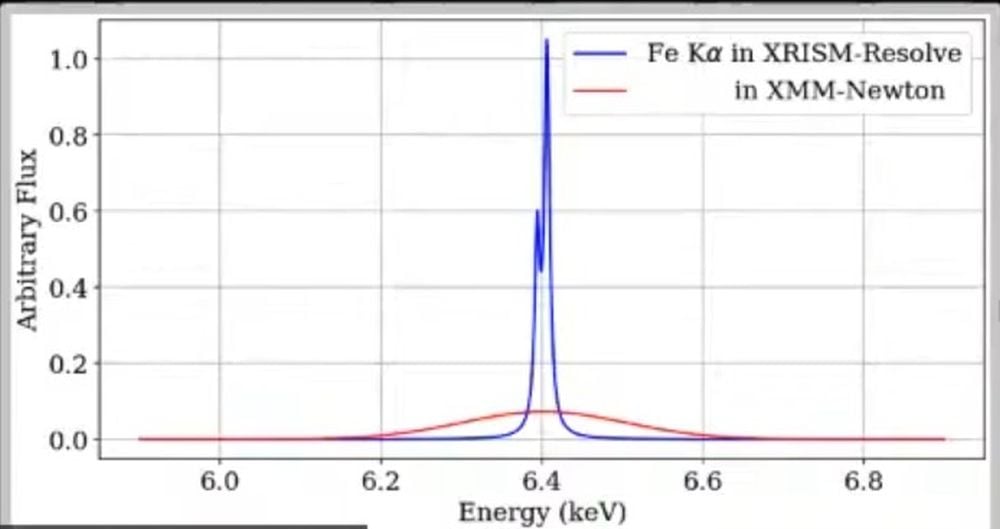

This image compares XRISM’s observations of the Fe Kα line to the same observations from an older x-ray telescope, XMM-Newton. XRISM’s observational power is far better than any of its predecessors, allowing for more detailed observations of the clouds in the galactic center. Image Credit: Stephen DiKerby.

This image compares XRISM’s observations of the Fe Kα line to the same observations from an older x-ray telescope, XMM-Newton. XRISM’s observational power is far better than any of its predecessors, allowing for more detailed observations of the clouds in the galactic center. Image Credit: Stephen DiKerby.

Sagittarius A star is very dim, barely emitting any light at all. That means it’s inactive. But it hasn’t always been inactive, according to this research.

DiKerby and his co-researchers used XRISM’s extraordinary power to not only observe G0.11-0.11’s motion, but to determine which of the potential causes caused it to emit x-rays: cosmic ray ionization or x-ray fluorescence. The telescope’s ability to resolve the x-ray light in great detail showed that x-ray fluorescence was the cause.

“This remarkable measurement shows just how powerful XRISM is for uncovering the hidden history of the center of our galaxy,” said Professor Shuo Zhang, director of the lab behind this work. “By resolving the iron lines with such clarity, we can now read the galactic center’s past activity in unprecedented detail.”

These observations mean that at some point in the recent past, long before we even knew what x-rays or SMBH were, it was active. Some time in the past few hundred years, possible a thousand years, Sagittarius flared brilliantly, and x-rays from G0.11-0.11 are the evidence.

“Exactly when such significant X-ray outburst happened depends on the exact location of each individual cloud and whether one or multiple outbursts happened

in the past a few hundred years,” the authors write in their research. Some previous research showed that there was one about 200 years ago, and other research suggest that there were two events, called the “two-flare” model.

“In the “two flare” case, G0.11-0.11 and other GCMCs (Galactic Center Molecular Clouds) are illuminated by a ∼ 230 year old flare while the Bridge cloud is illuminated by a ∼ 130 year old flare,” the authors explain. “The more recent flare would eventually travel to G0.11-0.11 and illuminate it again in a few decades.”

It’s truly remarkable that humanity has an orbiting space observatory capable of observing x-rays in such fine detail, and and that scientists can use those observations to piece together the historical activity of an extraordinary object like Sagittarius A-star. It was only a cosmic blink of the eye ago that we had no idea any of this stuff even existed.

“This remarkable measurement shows just how powerful XRISM is for uncovering the hidden history of the center of our galaxy,” said Professor Shuo Zhang, director of the lab behind this work. “By resolving the iron lines with such clarity, we can now read the galactic center’s past activity in unprecedented detail.”

Lead author DiKerby is similarly enthusiastic.

“We’re just the lucky scientists who got to solve the problems with handling this data in this brand-new way,” DiKerby said. “One of my favorite things about being an astronomer is realizing I’m the first human to ever see this part of the sky in this way.”

The historical flaring activity revealed in this work can tell astrophysicists a lot about the SMBH. It indicates that there was a recent feeding event. Sagittarius “consumed” either a star or a gas cloud in the recent past. More detailed study can reveal how the SMBH switched from quiet to active modes, and can also reveal details about the dynamics of the black hole and its environment.

This work won’t end here. There’s much more to learn about the remarkable environment in the galactic center, including Sagittarius A-star and the gas clouds that inhabit the region.

“Future X-ray monitoring of GCMCs will test the “one-flare” and “two-flare” models, characterize the unique dynamics of each GCMC, and create a more comprehensive map of the Galactic center region,” the authors conclude.