Earlier in the quarter, I attended a performance of The Lion King along with a cohort of students from my dorm. The musical was enthralling, yet every few minutes the conspicuous white glow of an iPhone’s home screen yanked my attention off the spectacle onstage and onto the stream of notifications quietly pinging in the lap of the student next to me.

Disruptions of this nature are no longer uncommon, and we seem to have accepted the nagging presence of our phones as an unavoidable byproduct of our attachment to the online world. But I find it particularly worrisome how phones distract UChicago students—who chose to join a community rooted in the “Life of the Mind”—from fully experiencing the artistic dimensions of an intellectual life. UChicago’s curriculum theoretically attracts people with curiosity in all intellectual endeavors, from the hard sciences to the arts. For physics majors excited to explore the notion of human fate and English majors eager to enhance their computational reasoning, the Core Curriculum is an opportunity for growth rather than a burden—a chance to expand one’s appreciation for subjects that they otherwise might never have explored and tap into interests they’ll never again have the chance to indulge. The arts Core, for instance, exists not to cultivate artistic mastery but to foster imaginative thought, contributing to a well-rounded intellect; nothing is expected of students who enroll in these classes beyond a willingness to explore. No matter what you intend to study here, approaching art with an open mind is central to making the most of the UChicago undergraduate experience.

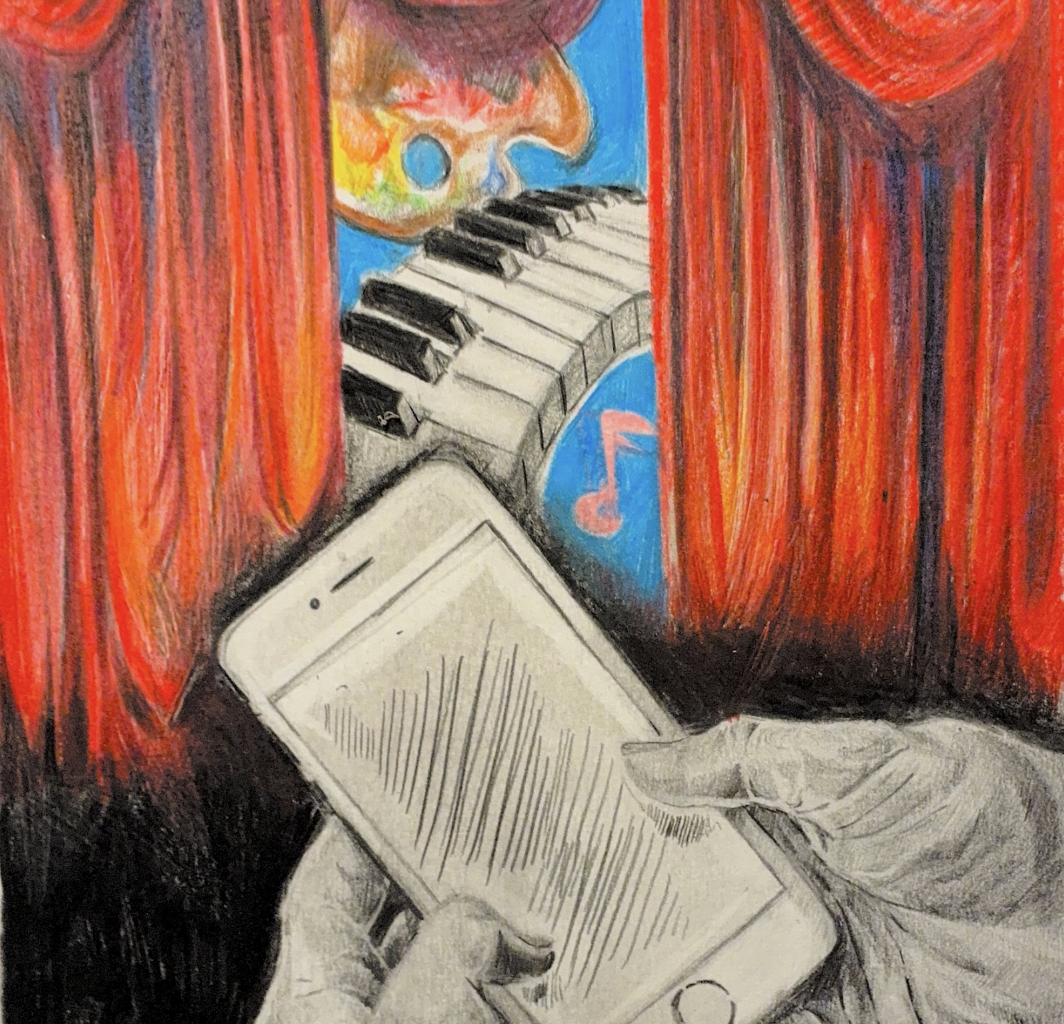

As UChicago students, we must ask ourselves: Are we willing to let our phones invade the delicate spaces we reserve for creating and appreciating art? It’s true that our phones function as legitimately helpful tools. We rely on them for academic and social purposes, reflexively pulling them out between (and during) classes to refresh Outlook, take photos of the chalkboard, and coordinate dinner plans. But as these tools improve, especially amid the rapid development of AI, we must resist the inclination to integrate them into every aspect of our college routines. Instead, we must separate them from the areas of life, such as art, where they do more harm than good.

To be clear, I’m not referring to art in its most broadly construed sense, which could reasonably include all types of creations, from TikTok videos to AI-generated images. I’m focused here on the kind of art that doesn’t heavily rely on phones or similar technology in its creation or presentation. There’s nothing inferior about crafts that use contemporary technology, but traditional art forms, such as printed novels, paintings, and live theater, have existed for thousands of years without phones, and we should keep them that way.

Aside from being addictive and distracting, like at The Lion King, phones undermine our engagement with these traditional art forms. For one, they weaken our curiosity. Search engines, and now AI chatbots, give us access to unfathomably vast amounts of information, which is collected, organized, and delivered to us within seconds of our search. While I celebrate the way the internet has made information more widely accessible, and I don’t dream of returning to a pre-internet era, the ease with which we find content online trains our brains to expect answers to all inquiries, atrophying the part of our mind that relishes sitting with the unknown.

Art, in contrast, thrives on the unknown. It contains not an abundance but a dearth of information. I was forced to deal with that scarcity when I first saw Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting depicts a man standing atop a mountain, his back facing the viewer as he takes in an immense landscape beyond. As I looked at the painting, I wished I could see the expression in the man’s eyes. I wondered if he feared the jagged expanse or admired it. Was he preparing to lean confidently over the edge or slowly back away? Of course, I could not search online for the answers to these questions. And though I found myself craving an online explanation to clarify the mystery of the painting, I ended up making my own story out of the clues that Friedrich provided. Just as the wanderer confronted the sea of fog, I squinted at the unsolvable painting, fighting the urge to find the right answer and instead embracing the joy of finding the right question.

It’s difficult for our minds to embrace tough questions when we fill every bit of our free time with our phones. We doomscroll for hours straight, but we also fill the little pockets of unstructured time—time during which we’re meant to think without constraint—lost in our phones. Go to any dining hall and you’ll see a large number of students eating while hunched over their devices, even when sitting with friends. Our obsession with productivity, our desire to feel like we’re doing something, though usually a helpful mentality, hurts us by rationalizing this as time well spent that we would otherwise waste away in the solitude of our own thoughts.

But these short instances of free time, whether waiting for the elevator, eating a sandwich alone, or lying in bed at night, give us a chance to reflect. Usually, my uninterrupted thoughts consist of nothing more than catchy songs (such as “The Circle of Life”) and annoying recollections of the last stupid thing I said to someone. Yet, in other moments, I’ll mull over a confusing chapter of the novel I’m reading or, if I’m passing through the quad, spontaneously look up at University’s embellished rooftops. In these mini periods of reflection, I let my mind go where it pleases. There’s no pressure to think efficiently or make progress—the very notion of efficiency is antithetical to art. As New York Times Book Review critic A. O. Scott said during a panel on art and literature, we should not attempt to suppress our boredom because a wandering mind engages in the creative process of connecting disparate ideas. This isn’t to say that we should contemplate the meaning of life every time we see a sculpture. We must not, however, deprive our minds of the space it needs to grapple with ideas it finds compelling.

Perhaps most detrimental to our engagement with art is the way our phones weaken our ability to empathize. Social media boosts aspects of our communication by keeping us in contact with hundreds of people at once. Yet by dispersing our attention across so many profiles, we spend less time forging deep connections, which are central to creating and appreciating art. In a recent University Theater production of Our Town, I played a character named George Gibbs, who lived in a small New Hampshire town over a century ago. Embodying George meant imagining, partly through my own experiences, what it would feel like to be reproached by a close friend and reprimanded by a father. It meant genuinely caring for George, his family and friends, and the seemingly mundane yet entirely authentic world he inhabited. Rather than splitting my attention among hundreds of people online, I focused my thoughts on the other characters onstage. Rather than taking in endless streams of stimulating content featuring people and events around the world, I listened carefully to and cared deeply for a small but meaningful group of people. Kevin Otos and Kim Shively write in Applied Meisner for the 21st-Century Actor that actors (though it is true for audiences too) must learn to empathize with the play’s characters because “there is an element of love for anyone that is worth your full attention.”

How can we repair our relationships with art? We might take inspiration from the schools across the U.S. that have begun banning phones for students. By reinstating phone-free zones, kids learn to value thinking without the distraction or assistance of technology. I appreciate my humanities Core class at UChicago for similar reasons. The class takes place in the Regenstein Library’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, which prohibits students from bringing most of their belongings into the classroom, giving me an incentive to part from my phone for a glorious 80 minutes. During class, I’m free to interpret the Iliad without the familiar weight of a phone in my pocket reminding me that ChatGPT could spit back an answer to every one of my questions.

But, while physically separating ourselves from our phones gets us closer to appreciating art, the habit alone won’t be enough to curb society’s unceasing push for technological integration. If we want to resist that push, we must shift our mindset toward phones by embracing the guilt we feel for our addictions. Most of us cringe when we check our screen time and calculate the hours per week, month, and year that we spend consumed by our devices—and we should feel ashamed. That shame springs from the part of our conscience that craves wonder, values empathy, and recognizes that there is something hollow about an existence without art. As UChicago students, with the privilege of attending a school dedicated in large part to the enrichment of the creative mind, we can either let our phones continue to encroach upon our lives or make an intentional decision to keep them out of certain spaces. At stake is our appreciation of art, which is to say, our appreciation of each other.

Alek Gideon is an first-year in the College