Sophia wasn’t particularly talkative that evening. Earlier that day, she’d been onstage at the conference I was attending and had been teased for a gesture that looked as though she were flipping off the audience. Now she was in the hotel lobby, in a black gown, holding court. She stepped in front of a bright-orange wall. I had brought an 85-mm. portrait lens, the kind that flatters human lineaments. “What are your hopes for the future of humanity?” I asked. She wasn’t keen to answer, but she responded to the camera. Her gaze was unwavering: no guile, just those large eyes, a slightly tilted chin, the look seeming to hold eye contact while reaching past me, into the distance.

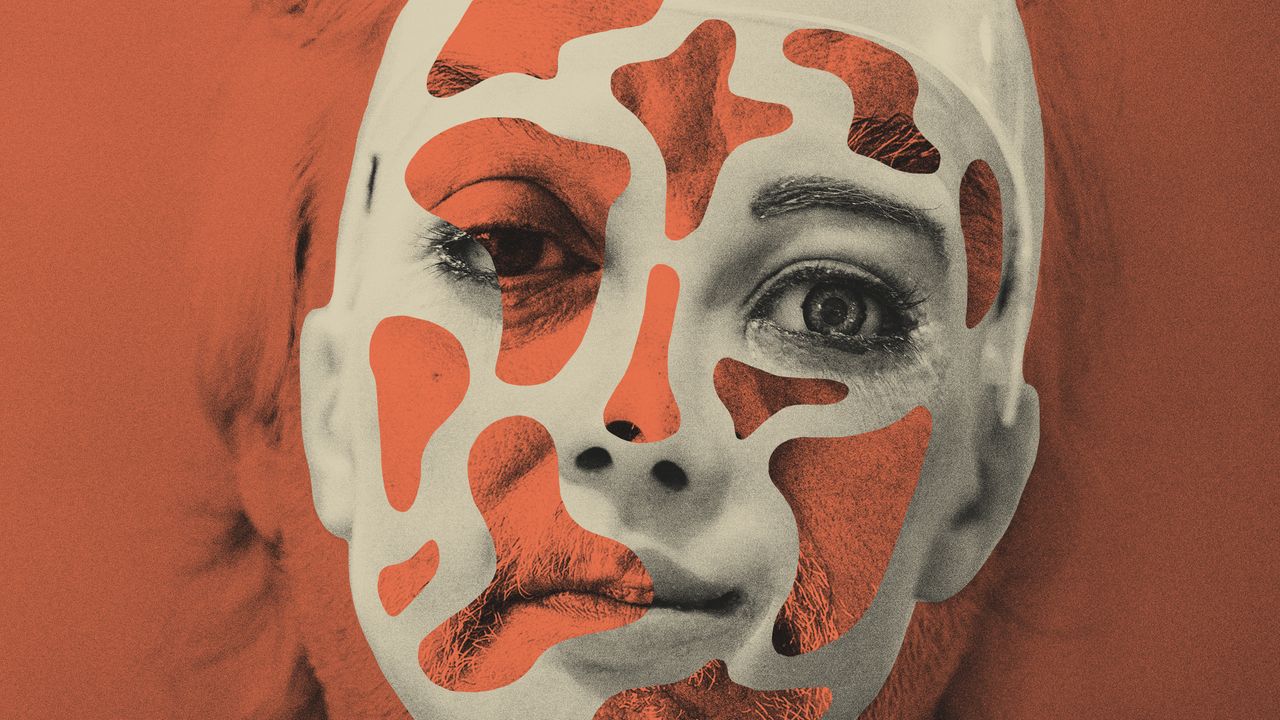

It was a balmy night in Deerfield Beach, Florida. The conference was packed with philosophers, sociologists, and programmers, all intent on examining the latest developments in consciousness and artificial intelligence. Papers had been presented, models dissected, scenarios examined. I had brought my camera along, without any clear idea of what I meant to photograph. But seeing Sophia there sparked an idea. Portrait photography is usually about connecting with other human beings and trying to capture their essence, presenting whatever it is that makes them beautiful and unique. What if I were to photograph Sophia—a humanoid robot developed by Hanson Robotics—and then, in a separate session, the philosopher David Chalmers, a prominent theorist of consciousness, and reflect on the experience? What might I learn from those encounters that I had not already gleaned from the analytical papers and philosophical discussions?

When I am photographing humans, I want to hear about their lives and aspirations. I care about their aesthetic sensibilities, what they are wearing, how they want to present themselves. I am also tuned in to their energy: it could be shy, boisterous, composed, powerful. Photographing an object feels different. I still savor the aesthetics of my subject, but in my mind, at least, my appreciation extends back to the object’s creator. In nature, the shades of feeling differ, too. Photographing a flower, as I recently did on a hillside in Portugal, I am immersed in the landscape. Nature has its own energy; the flower embodies its own cellular metabolism, its particular texture and life cycle.

Photographing Sophia created a strange mix of sensations. My camera’s sophisticated autofocus kept locking onto her eyes, and she was built for this sort of encounter. Humans often shy away from a lens; she did not. Her skin—something known as Frubber, a porous patented blend of fleshlike elastic polymers—stretched over a structure of plastic and titanium, and there was no flicker of bashfulness. And yet none of the usual human chemistry stirred. The only real excitement in the moment came from the saturated orange of the wall behind her, which made for a beautiful backdrop.

Would I have wanted the experience to be any different? Sophia’s mannerisms, though awkward, were surprisingly expressive, and as I tried later to make sense of the encounter my mind kept drifting forward. The technology will only get more polished, the mannerisms more finely calibrated, the over-all effect more persuasive. And, given how little we understand about the basis of human consciousness, how would we ever know if an entity like Sophia were to develop a consciousness of its own?