This weekend feels different across the Bay Area. Clouds are in short order and the air is notably dry after weeks of moisture, both signs that for the first time in nearly three weeks, California has shifted into a sustained dry stretch.

It’s a welcome change after a soggy late fall and early winter that brought repeated rounds of rain in November and December, followed by a stubborn stretch of dense tule fog that blanketed the Central and Sacramento valleys for weeks.

But January is one of the wettest months of the year for the Bay Area, and the question now is: When does the rain return?

The short answer is that there’s no strong signal pointing to rain coming back anytime soon. Long-range weather models are unusually consistent on this point.

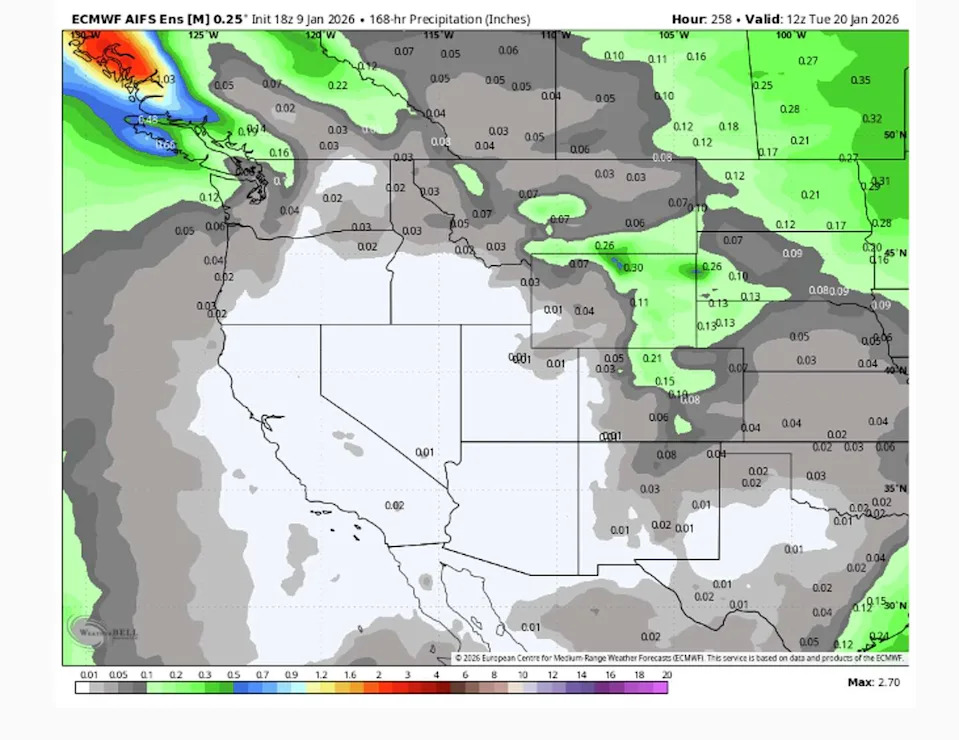

In the near term, there’s little drama. Multiple long-range models agree that California will experience a dry stretch at least through the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend. And while there will be some day-to-day microclimate driven discrepancies, like a return of persistent fog next week, there won’t be any organized storm systems bringing rain or mountain snow.

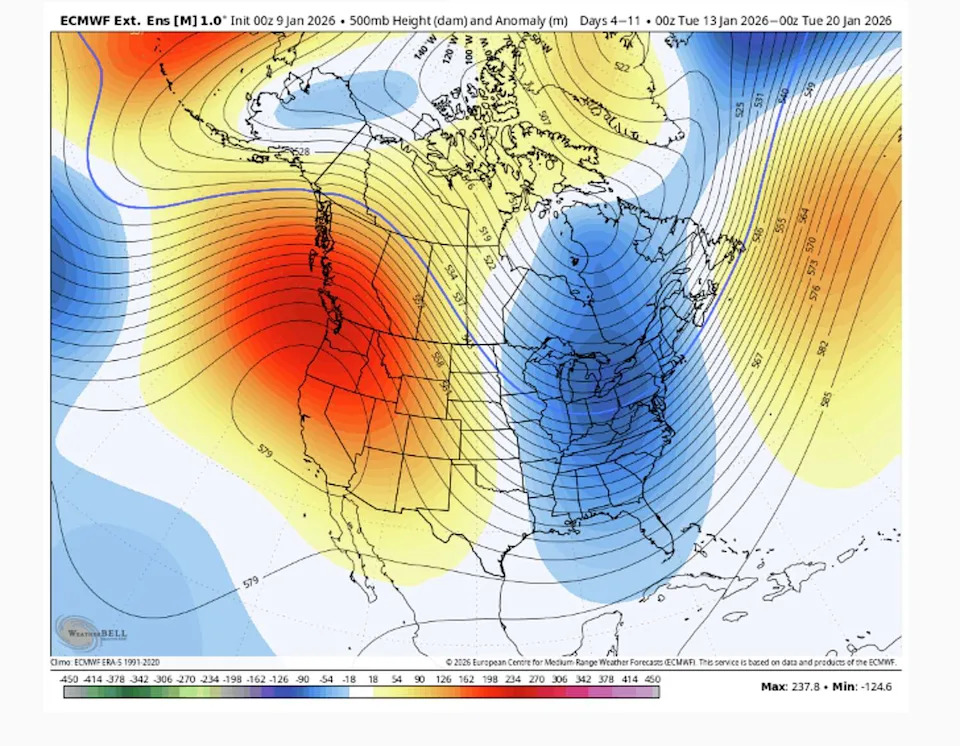

Welcome back to the Pacific high pressure ridge. The large red and yellow blob over the West Coast represents an area of high pressure that will keep storms away for the next 10 days. (WxBell )

After MLK Day, forecast certainty begins to drop off. The timeframe from about Jan. 23 into early February falls into what meteorologists often call a low-confidence window or a period when the atmosphere starts to show hints of change, but without enough agreement among models to lock in a specific outcome. That doesn’t mean rain is imminent. It simply means the pattern becomes less rigid and more variable.

The reason comes down to the atmospheric setup over the Pacific. During California’s recent wet stretch, the jet stream was aimed squarely at the West Coast, steering one atmospheric river-fueled storm after another into the region. That alignment has since shifted.

High pressure has rebuilt over the eastern Pacific, nudging the jet stream and storm track north. With that ridge in place, storms are steered away from the West Coast and into Canada, bringing not only a dry stretch to California, but to the recently drenched Pacific Northwest as well.

Long-range forecast models show almost no precipitation for the entire West Coast through Jan. 20. (WxBell )

What’s notable is how slowly that weather pattern is forecast to evolve during this time. Rather than collapsing outright, the ridge of high pressure is expected to weaken gradually. That distinction matters. A weakening pattern doesn’t guarantee storms return right away; it simply opens the door to the possibility that the storm track could eventually dip south again.

It’s also the kind of scenario that long-range weather models struggle with.

As January shifts into February, there is a notable split in forecast model outcomes. Some scenarios show the ridge of high pressure retreating or flattening enough to allow storms closer to the West Coast. Other scenarios rebuild the ridge or keep it close enough to continue deflecting systems away. No single outcome dominates, which is why the uncertainty is high for this time frame.

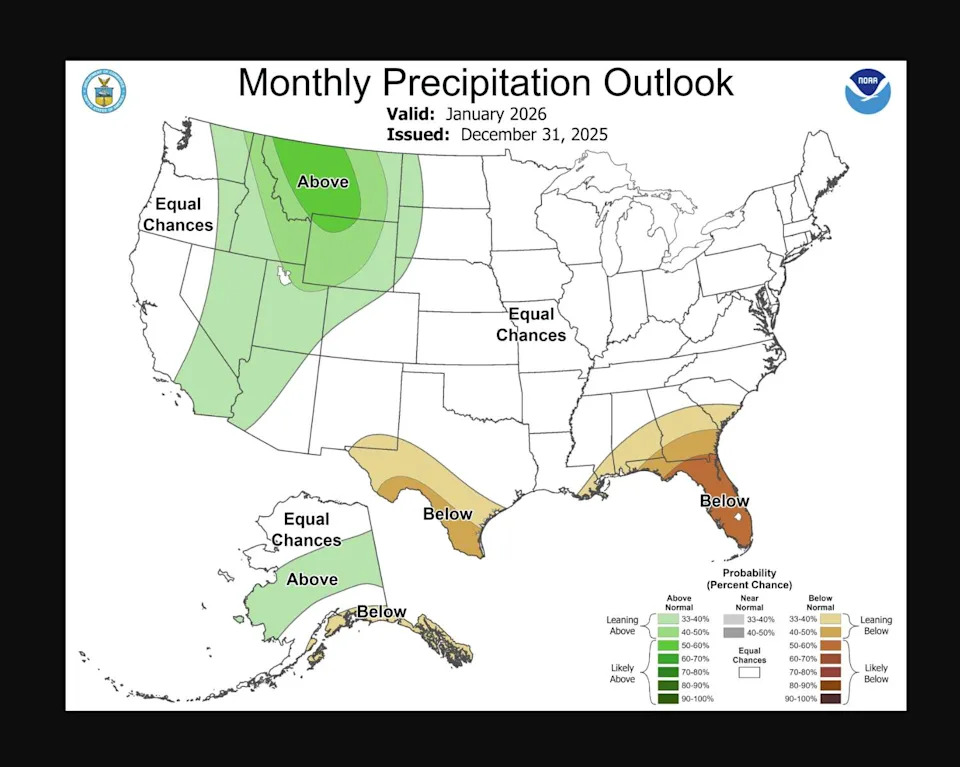

The January precipitation outlook from NOAA shows little to no precipitation in California. But also comes with a high degree of uncertainty. (NOAA)

For precipitation to return in a meaningful way, several ingredients would need to line up at once. The Pacific ridge of high pressure would need to shift farther west, the jet stream and storm track would need to dip south toward California and colder air aloft would need to align with incoming moisture. Right now, those ingredients appear together in only a subset of long-range model solutions.

That makes late January into early February the first window worth watching more closely, not because precipitation looks likely, but because it’s the earliest point where the atmosphere appears capable of supporting a change. Whether it does remains an open question.

This article originally published at California storms have suddenly shut off. When will rain return?.